Undateable: Some Reflections on Online Dating and the Perversion of Time

Lucas Hilderbrand / University of California, Irvine

Romantic relationships have long been defined in terms of duration: anniversaries, long-term relationships, summer flings, and one-night stands. The courtship experience can likewise be understood as an experience of subjective time: the anticipation of longing, the ecstasy of timelessness during lost weekends, the performance anxiety of keeping it up, or the end of an era marked by a break-up. The concept of temporality has become central to queer theory of late, and while this column does not build from this scholarship directly, the very concept that sexuality is experienced in and across time has informed my own recent reflections on online dating. Here I think through the ways conceptions of past, present, and future interpenetrate, and they ways that the subjective experience of online dating can fuck with one’s sense of time.1

Future

The marketed temporality of online dating is futurity: that, if a user logs in, they will find a partner. The allure of online dating is the belief in a structure of possibility: in this utopia (virtual non-place), you will find the perfect match. Using interfaces of self-representation and algorithms of compatibility, various sites suggest that there is, at least in theory, someone for everyone and that the most efficient way to meet is via database calculations. More than once, I’ve been advised that the only way to meet people is to go online. This mythical structure of possibility suggests that, if you keep searching, you will find someone, but also that there might always be a better match in the future. There’s an illusion of unlimited options and a continued hope that new and better matches will come online. Thus, there’s also a recurrent temptation for deferral.

In my experiences—and those of friends with whom I’ve compared stories—the effect can be one of increasing selectivity, that the implicit promise of inexhaustible and perfect matches can prompt users to reject potential dates for any number of minor flaws, from punctuation errors in messages to pop culture tastes to unflattering angles in profile pics. Such turn-offs repeatedly also reveal the shortcomings of computer matching: regardless of the percentiles calculated based upon surveys of users’ self-defined values, there is no accounting for attraction. No computer can predict chemistry or affect; it can only narrow selection down to often arbitrarily articulated interests or often ill-fitting broad identity categories chosen from a limited range of options in a drop-down menu. The architecture of the profile’s fields frequently pre-determines they ways users can self-represent.2

The process of writing one’s profile is also a process of imagining one’s future readers and writing toward a desired response. Writing a profile is a kind of labor time; I’ve even read profiles that suggest that the author should be paid for writing. Along similar lines, in their song “Personal,” members of The Ballet sing, “Saw you on Gaydar/Your profile was so clever/The references to Baudrillard/Must have taken you forever.”3 Self-representation becomes a calculated investment in future return. For subscription sites, what is paid for is time: monthly fees for access. Messaging drives toward the ultimate goal of arranging a future date. One of the differences between gay and straight online dating, however, is that there seems to be far more fluidity about what form new relationships will take. On the one hand, the technology might more frequently lead to quick hook-ups for gay male users, but for same-sex dating, there’s also far more likelihood that dating sites function as social networking and that relationships facilitate online will actually transition into platonic friendships.

Present

If the draw of online dating is the promise of a future match, the experience is primarily one of the instantaneous and the interminable now. Searching online personals is real-time experience, one that can quickly become rote but nonetheless compulsive, as users click through to the next page of search matches. Browsing at profiles can as often as not be an act of procrastination rather than directed searching. Sites track and tell users when each person is online or when they’ve last logged in; they also indicate if it’s been awhile since a person has been contacted—thus marking undesirability or potential desperation. But there’s also a privileging of the new: new members are promoted on homepages, searches, and auto-messages. Likewise, existing profiles are flagged when they are updated. Thus, there is a logic of planned obsolescence, wherein the new member or the updated profile is preferable to the pre-existing options. The impulse toward instantaneity perhaps counteracts the thoughtful reflection that should perhaps undergird romantic involvement, so that even if you want a long-term relationship, you usually want it to start now. Thus, there’s a contradiction of impulses and expectations.

Online dating inverts the typical temporal structure of finding and flirting: looking for potential mates, which in the real world takes time, is nearly instantaneous with search engine technologies, but the temporality of interaction, which would be the temporality of looks and conversation in person, unfolds in mediated time full of delays, from the gap in time until someone checks messages to the time it takes to compose a response to the likelihood of waiting for a reply that never comes. Waiting is an age-old experience of dating. Yet, the temporality of online dating is supposed to be one of instantaneity: with online chatting, smart phone apps, and instant email auto-forwards. Thus, the duration of the present is intensified, as the expectation of instant reply can make now feel like forever. Upon subscribing, as with Facebook or other kinds of sites, initial rush of absorption can easily turn into unplanned hours of profile writing (and revising), searching, and messaging. Online dating sites’ frequent email alerts with new matches or, even more maddeningly, anonymous notices that someone has looked at and rated your profile, attempt to drive traffic back to the site with regularity and repetition even after the first blush of excitement. Being on the receiving end of such incessant bot messaging can at times be neurosis-inducing, as it teases the user with both potential mates, reminders of the limited options, and probable rejection. I quickly learned that non-response has come to be an accepted social custom through online dating, and even people with whom one exchanges messages might disappear without explanation. One quickly relearns social mores and customs, which differ online from in-person communication. But the temporality of response also communicates, so that a delayed reply probably suggests limited interest, unless there are apologies indicating otherwise. The present becomes a mix of seeking and waiting.

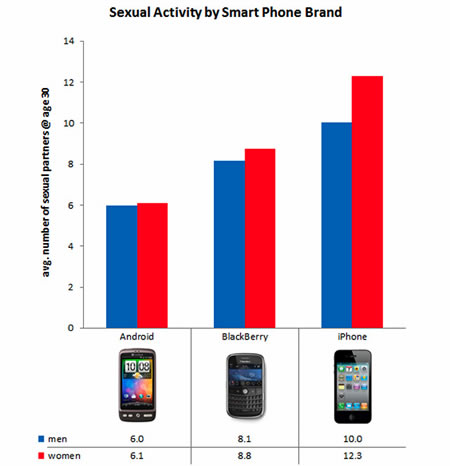

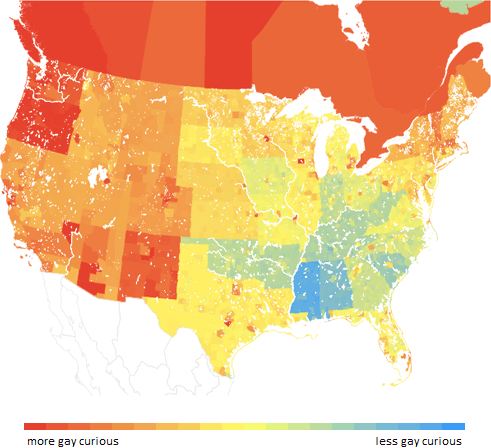

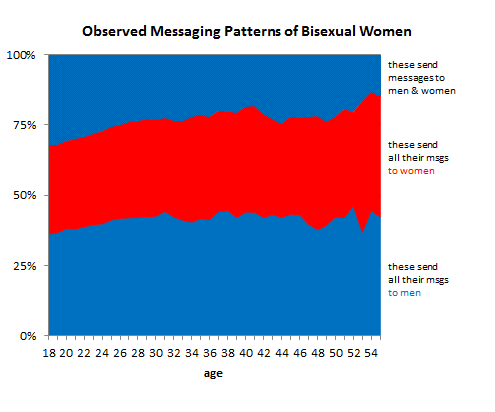

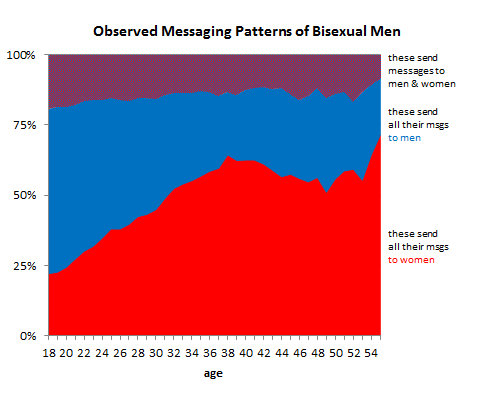

But through user tracking, sites such as OK Cupid also become repositories of data, which reveal information about our contemporary moment. OK Cupid has released graphs that suggest statistics of self-identification, desire, and perhaps most tellingly, actual messaging behavior. Perhaps OK Cupid is the new Kinsey Report? Yet even here, the allure of quantitative data can tell us little about qualitative matters of affect, desire, and satisfaction.

Past

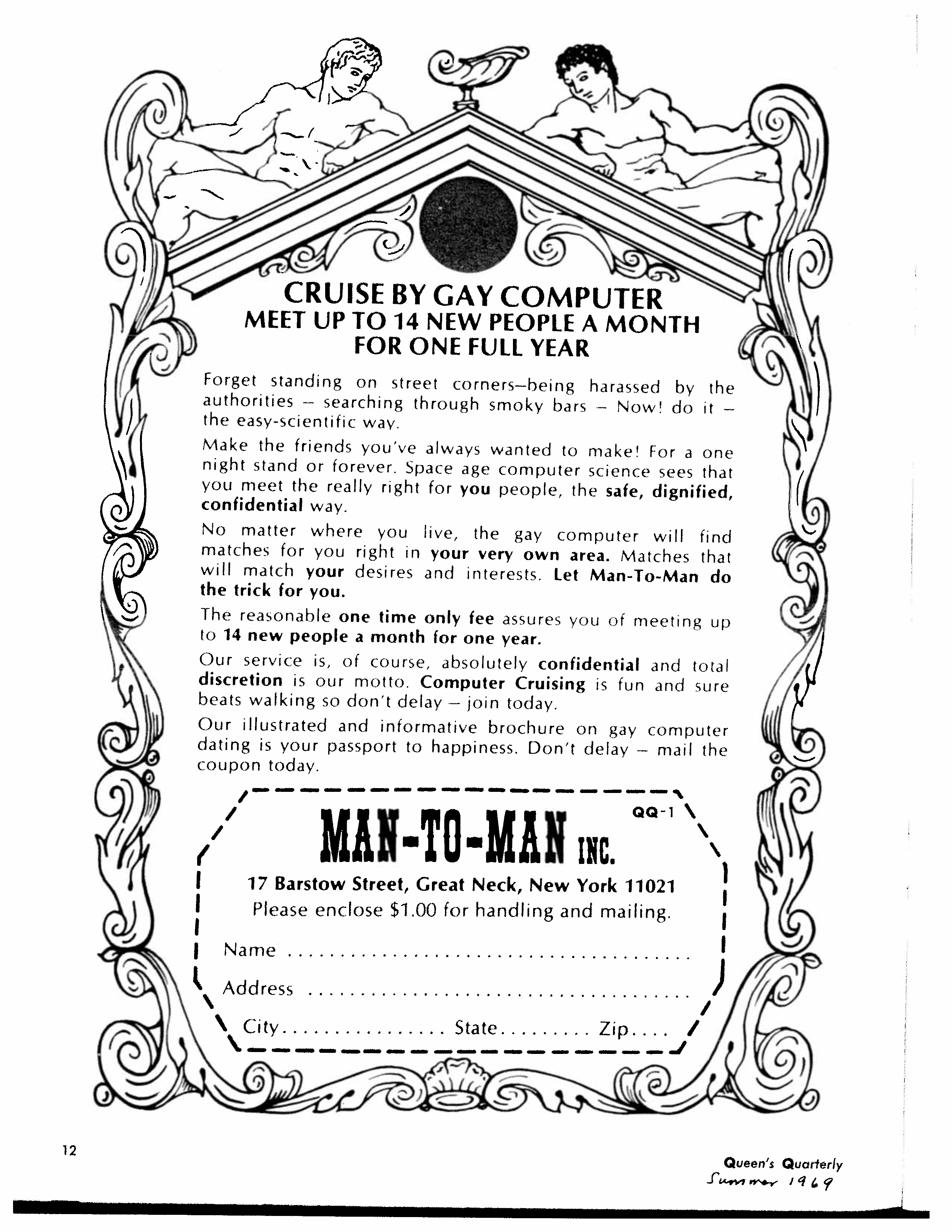

Online dating has a history. If it is, indeed, the only way to meet people now, by resisting online dating for the better part of a decade, I was behind the times when I eventually began this social experiment. But around the time I first began considering going online, I came across a couple of curious ads for Man-to-Man “gay dating by computer” dating from the late 1960s. The promise of computer technologies to rationally make romantic matches stretches back further than we might expect, to the pre-world wide web days. A 1968 ad that ran in the San Francisco-based magazine Vectors and the New York-based glossy magazine Ciao promises that punch card-era computer matching would be scientifically sound. The ad’s simple line-drawing image curiously, however, retreats from the new media of the mainframe to neo-classical iconography. A year later, the ad’s text was updated to contrast the real and the virtual worlds of cruising: “Forget standing on street corners—being harassed by the authorities—searching through smoky bars—Now! do it—the easy-scientific way.” Already technology was imagined to intervene and make romance efficient and clean; what would potentially be lost were spontaneity and the thrill of transgression. In this new age of dating, time was of the essence: the ad repeatedly urges potential clients, “don’t delay.” This document of new media before new media suggests both that the desire for online dating predates the technology itself and perhaps inverts the ways we imagine the history of invention and the development of social networking.4 But it also promises instantaneity, despite the fact that a mail-order computer service would take longer to process than a street pick-up. Yet, perhaps again the difference was that a rational match was imagined to last, where as a trick would be temporary.

Going even further back, Alan Turing, the homosexual inventor of the computer, wrote of his Automatic Computing Engine in 1947, “the machine must be allowed to have contact with human beings in order that it may adapt itself to their standards.”5 Biographer David Leavitt suggests this sentimental computer science reflected the inventor’s own sense of social isolation and projections of the desire for contact. The history of the computer reveals that it was not only a calculation machine but also one that was always informed by the desire for human connection and the romantic notion of rational matching. The history of technology is always a history of an imagined future, though the ways technology becomes adopted by users often departs from the inventor’s fantasies. The rational and emotional, the quantitative and qualitative are always intertwined. Going online to find sex, love, and companionship is an act of the present with an eye toward the future, but it has unexpected connections to the past.

Image Credits:

1. Sexual Activity by Smartphone

2. Chemistry.com

3. OK Cupid Map

4. OK Cupid Chart 2

5. OK Cupid Chart 2

6. Man-4-Man Computer Dating Ad, Queen’s Quarterly, Summer 1969

Please feel free to comment.

- My thinking has been informed by Alexander Chase, Corella Difede, Patrick Keilty, and Shaka McGlotten and their presentations on the recent SCMS panel “The Virtual Life of Queer Sex Publics.” [↩]

- On technological structures and regulation, see Tarleton Gillespie, “The Tales Digital Tools Tell” in New Media [↩]

- The Ballet, “Personal,” Mattachine! (2006). [↩]

- Lisa Gitelman has examined historical aberrations of iterations of the internet before the internet in Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006). [↩]

- David Leavitt, The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer (New York: Norton, 2006), 208. [↩]

Great stuff, as always!

I couldn’t agree more with your article, and have found everything to be spot on, from both personal experience and from talking with friends. I actually want to expand a little more on what you wrote, by drawing some analogies between online dating and reality TV dating shows, that I believe influence the way we behave and search for potential mates as a new kind of entertainment.

The way we find mates and proceed with courtship has been drastically influenced by not only internet and smart phone apps, but also by the media and the way we consume them. There was a time when “You’ve Got Mail” was edgy and modern, where America was showing through a major studio production to the rest of the world what the future of dating could become thanks to the Internet. Looking at what we have now, we’ve moved faster and faster in very few years, and “You’ve Got Mail” almost seems coming from a lost age of romanticism — and what to think of the original “The Shop Around the Corner”?

While films remain fairly classical as to human relationships and courtship, TV followed closely the revolution that was happening online–and actually preceded it. In 1965, ABC aired the first dating show in America, the “Dating game.” That was the first attempt at changing courtship by making it public. Recent reality TV shows add even more complex elements, including large sums of money, transforming courtships into drama and entertainment. There are countless TV shows out there that explore this kind of dating, such as “The Bachelor”, “Blind Date,” “Dating in the Dark,” “Next,” and so forth. Not only do some of these have their queer equivalent — “Next” has an exclusively gay version of its show — but the formats have been adapted in foreign territories (I will note there that this flow of dating shows is a two way street, as “Dating in the Dark” was adapted in the US from a Dutch show, and exist in various countries in one version or the other, such as France, Australia, Brazil, etc). These shows influence and emulate how we date, and all carry out elements that you mention in your article. Writing a witty profile to make yourself appealing on Ok Cupid is much like presenting yourself in a hip way on “Next”, and saying “Next” to another contestant on the show is like clicking “Ignore” on Ok Cupid, or even not responding to a message at all. In addition, both in “Next” and Ok Cupid do we find this idea that you talk about regarding the future: the necessary existence of a better mate.

I would take the next step from your article and propose that, at least as far as gay men seem to be concerned, online dating is entertainment: it is a game with a public quality (a profile), it is immediate (click next or respond right away), it has its own prizes (get a sexual “hook up” or perhaps a new friend), and the people involved are constantly looking for the next best thing. Grindr, a mobile location-based application to meet mates, is a striking example of dating entertainment on the go. The novelty about Grindr is that it took the online dating realm from the computer to the palm of the user’s hands, so that it can be used anywhere, even at a bar where a more “traditional” kind of courtship is almost no longer expected. How more immediate can it get, when the profile you are checking out belongs to a potential mate standing a few feet away from you, in the same bar? Then again, why not ask ourselves: couldn’t you just go talk to him for real instead of using Grindr to break the ice?

Finally, I’ll finish with a few words on the globalization of dating habits for gay men: TV shows and films are not the only transnational flow of media displaying/offering new ways of dating. Grindr works worldwide, and for the one who finds himself at the border between Spain and France, gay men from both countries log on the app at any hour. Habits that are to be found on OK Cupid/Grindr in the US do carry over in Europe, so that there is a worldwide leveling of dating etiquette: ignore if you’re not interested, ask for more pictures if you are, and ask “what are you into?” right away to waste as little time as possible. If it’s a match, enjoy your sexual “gaytertainment”, and if not, you simply have to say “Next.” ;-)

I too found this article to be right on with my own experience and observations as well. Technology is a double edge sword that simultaneously enables greater ability for communication while creating higher fragmentation and isolation between groups and individuals. Online dating sites are an example of this dilemma.

Much like cable television or the Internet, online dating brings many options to its users. Users can self-identify with niche groups based on personal interests, political affiliation, race, gender or religion. I fear this greater ability for identification with these fragmented groups can hinder communication and relationship between groups. This can be particularly seen in the current political climate in the country.

Online dating services allow users to only meet people within the group they identify with. Of course this can be a tremendous blessing, however, I wonder what is lost. Online dating allows users to categorize themselves and know how others have categorized themselves. The journey of discovering how someone is, what they believe in, what makes them tick is lost. The interplay between the known and unknown is lost. If users stuck to specific identity groups, the potential to meet others from different groups is lost.

Pingback: COMU3005 – post 3: Are you on for online dating? | Annabelle Amos

That was really a cool piece of writing. I like a person who actually put in the time to produce impressive stuff – it is all a learning curve at the end of the day. Really well engineered and put together. Brilliant.