Fear Factor: Fun, Freedom and Foreignness on Burmese TV

Andrew King / Consumer Research and Communications Consultant

After completing my PhD in Media and Communication in 2007, I spent a year in Burma – partly to get away from the formal studies of university whilst my thesis was being marked (it took a whole year!), but mainly to relearn the Burmese language. Before returning to Australia, and being a Film & TV graduate, I sought to find the national archive of films, which was located at the end of the long, narrow muddy road just outside the city centre. On my way back to the hotel I met a film director, who was a bit drunk and very happy to talk to me in Burmese. We shared a taxi (as mine had gotten bogged in the mud) and talked about local television. He said he had an idea for a new program – a kind of It’s a Knockout, with contestants running inflatable obstacle courses lubricated with water and different colours of slime. He told me the idea was based on a program he saw in the UK whilst visiting relatives many years ago, which judging from his description would have been around 1985. For Burmese audiences, I thought his idea was very appropriate and achievable given the political context – one that could introduce some fun and reality into the local industry, without evoking the wrath of government censors. The reason for it not being commissioned, he said, was that censors did not want to encourage too much ‘fun’.

It’s difficult to imagine a television industry without any sense of fun or frivolity, even under military regimes like Burma’s, where programs may appear plain to the foreign viewer at first glance. Productions are scrutinized for material deemed ‘critical’ of the junta, which could include a brand name on a t-shirt, such as the word ‘revolution’, or a casual comment made by actors about life overseas. Of course Burmese audiences enjoy locally-produced content (so long as it’s not the news), however technically compromised it may be. Productions have extremely low budgets, reflected in shoddy sets, uneven sound levels, boom microphones entering the frame, long pauses between segments, and cueing errors when playing pre-recorded material. But like many other national audiences, viewers enjoy a hybrid of local and international favourites. Locally produced reality-style karaoke programs, traditional anyeint (dance-show comedies) are broadcast alongside Korean soap operas and Premier League football matches, dubbed over with Burmese presenters. Although I’ve enjoyed watching these programs with friends and acquaintances, one program in particular seemed to evoke the most intense curiosity about the foreignness of its fun – Fear Factor.

The Program … in Burma

Fear Factor is a globally successful reality game show produced by Endomol, where contestants compete against each other by performing dangerous or gut-wrenching feats. The original production is broadcast throughout Asia, and the format has been sold to local production companies in a number of markets in the region, including India and Malaysia. It is the American version which reaches Burma via Thailand, where it is screened with either Thai voiceovers or subtitles. Episodes introduce ‘ordinary’ fans to the show, who participate in various dares and challenges for cash prizes. The format distinguishes between three types of challenge – the ‘physical’ dare, where contestants do something physically dangerous, such as running obstacle courses on top of travelling vehicles or with animals (alligators or snakes, for instance); the ‘stunt’ dare, where spectacular action scenarios, like jumping from a burning car, are orchestrated for teams to compete against each other; and the ‘gross out’ challenge,1 where competitors tolerate something disgusting, like sitting in a bath of cockroaches or eating spiders. Even in places like Burma and India, where poverty produces its own corporeal encounters with nature’s nastier elements, the popularity of this simple format demonstrates an appeal crossing new cultural boundaries.

In Burma, Fear Factor is broadcast through the AXN network to business owners and middle-class pay TV subscribers. But for most viewers, access to satellite television is often a public affair – people frequently congregate at shops or public places to watch some of the few satellite programs available. The public nature of television consumption means that conversations about programs often take place in public. I first became interested in local reactions to Fear Factor in Yangon at a coffee shop I used to visit, where foreign TV programs, like the foreign customers they rarely attracted, became a sign of wealth and upward mobility. Inside, as I watched a family scoff down different containers of live insects, I also noticed a curious crowd gathering outside. As the AXN station was always on at my hotel reception, I also had many local visitors watching the show (at breakfast time), some of whom encountered it for the first time. It was also useful to improve my Burmese with the hotel’s waiters and receptionists who also watched the program.

Fun, Freedom and My Foreignness

Unlike other foreign programs broadcast in Burma, Fear Factor triggered many conversations about what it might be like to live overseas. After several months of occasional discussions with friends and acquaintances, it became clear that their interest in the program quickly moved beyond the simple ‘oh my God, that’s gross’ response, to questions about the program’s location, prize money, the value of credit cards (one of the main prizes), relationships (how groups of people are organised into teams, or chosen as families) and general lifestyle in America (values of the people participating and watching). By contrast, the English Premier League by contrast, perhaps the most popular satellite program in Burma, sparked little interest with viewers about location or culture. After all, it is a sporting contest, and money is often at stake. Korean soap operas are so popular in Burma that tales of families saving diesel fuel for generator power to watch weekly installments are common, but narratives are about drama and intrigue so viewers tended to discuss unfolding events and character motives. Besides, people also knew I was not Korean.

My most memorable observations of Fear Factor in Burma were in the countryside, a place where so few people have access to power, let alone local or international TV. But in rare visits to nearby town centres, where tea-shops broadcast television and DVD’s, there is a genuine novelty among people about watching foreign content. My fiancé’s family are such people, with whom we met at a tea-shop during our travels to the Shan State. Stories of the program were enthusiastically retold when her family returned to friends back in the village. Fear Factor was a form of cultural capital for those who had seen it, something to ‘show off’ about. Eating a scorpion was described with disgust and intrigue, but something that was evidently possible somewhere else. There was no illusion that Fear Factor represented normal life in America, but it offered the promise of entertainment in its most crude and basic form. There was amazement that a competition where crawling insects on a person’s head could be made into compelling television.

I’ve always enjoyed the program myself&8212;the over-competitiveness of contestants, egged on by the ever boastful and arrogant host, Joe Rogan. But I’ve noticed that these aren’t the things that interest my Burmese friends. When watching the show together, they’ve asked me how much people win as prize money, and what they may spend it on; how the home viewers use the credit cards presented to them as prizes (there are no ATM’s or any form of electronic banking in Burma); how people are selected as contestants; and how they pay for transport costs. It may just be that an overall lack of foreign programming in Burma has left Fear Factor with a monopoly on popular Burmese conceptions of real life overseas. But even if this is so, I found it interesting how an otherwise frivolous and non-serious program in my own country, could provoke such curiosity about life within another country. Watching contestants out-eat each other with puss spewing cockroaches, pizzas covered in blood worms and fish eyes is an exercise in fun, and on Burmese television it became more reminiscent of actually going overseas, escaping the boredom and non-freedom of home.

The Politics of Fun and Craziness

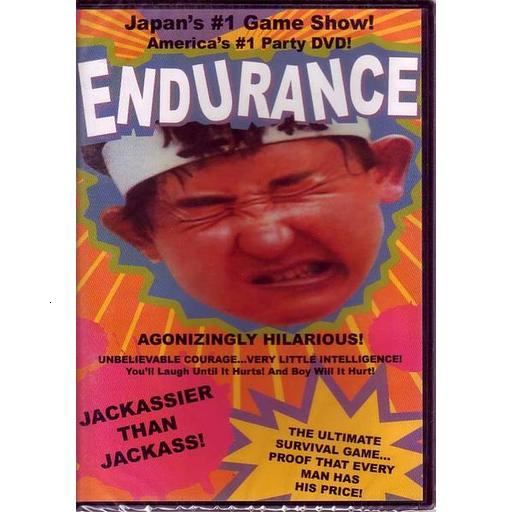

In a cultural context lacking certain self-representations of freedom, it’s quite telling that a program like Fear Factor may evoke curiosity about everyday cultural values elsewhere. The politics of fun, of non-serious, non-professional and gut-wrenching competitiveness in Fear Factor is an expression of young, ordinary people’s television interests in many countries. In the 1980s, for instance, The Clive James Show featured segments from the popular Japanese program Endurance, which similarly tested the endurance of mind and body. One of the most famous examples was an exercise in bladder control, after contestants drank gallons of water and rode donkeys in tight jeans. The ‘craziness’ of Japanese culture for British viewers became part of James’ comedic commentary, but it was an exoticized craziness that could only be made sense if it was viewed as being part of a liberal, Japanese culture. I can only guess that it is with this kind of exoticism that Burmese people view Fear Factor, only with more urgency about wanting to participate. In Burma, ‘fun’ is dangerous, even – or especially – if it can be related to our more immediately accessible emotions, such as the fear of spiders or a dislike of creepy cockroaches. Despite its growing popularity in other markets, a local version of Fear Factor may be some time away for its Burmese fans.

Image Credits:

1. Fear Factor

2. Local Burmese Family watches Fear Factor

3. Promotional Image

4. Japanese show Endurance

Please feel free to comment.

- The ‘gross out’ is a term I’ve borrowed from Kurosawa, Kiyoshi (2009) ‘Fear at a distance’, Pop Matters Website, available online at http://www.popmatters.com/tv/reviews/f/fear-factor.shtml [↩]

So we have been always waiting for this.