1979 is 2011: Post-Punk on the Road Again

Norma Coates / University of Western Ontario

My tickets to see Gang of Four in Toronto next month just arrived. I just listened to the new Wire album. The Raincoats just played in New York City. I missed Mission of Burma in Toronto a few months ago. Isn’t 1980 grand? SCREETCH (that is, sound of needle scratching across a vinyl album). This is all true as I write at my computer in early 2011. It’s a great time to be a middle-aged ex-punk rocker, or more accurately, a fan of early post-punk, because I can now see the bands that I missed seeing the first time around, or relive what it was like when we were all much younger. But wait, isn’t this somehow “wrong?”

When the Sex Pistols reunited for the first time for their 1996 “Filthy Lucre” tour, I thought it was a very punk thing for them to do, a figurative gob into the faces of those critics and fans who wanted to idolize and mythologize them as somehow outside the lure of the crassly commercial. But Gang of Four?! They’re Marxists, aren’t they? Why are they on the road again? And what’s with that slick website? What happened to ideological purity, and authenticity, that dividing line between the good and the pop? To me, the “70s and 80s in the 10s” is yet more evidence of the death of youth music and the possibilities that offers to previously marginalized audiences, discourses, genres, musicians, distribution platforms, and more.1 Moreover, the phenomenon also illustrates how tied notions of authenticity and other rock mythologies were tied to the industrial logic and health of the “old” music industry and its inadvertent minions, including rock critics, scholars, and even fans. Some of today’s revived bands are deftly using the web, especially social networking, to if not exploit then mobilize the nostalgic tendencies of their older fans, the curatorial tendencies of younger fans or wannabe fans or hipsters (choose one or several) to market themselves to them minus the mediators, that is, old school record labels.

Old bands reforming and touring is almost as old as rock and roll itself. Tours of 70s and 80s rock bands of the vaguely heavy metal ilk are as much a sign of the suburban summer as gas grills and mosquitoes. Then there are the bands like the Rolling Stones who forgot to break up. Yes, the oldies circuit is well travelled. But the return of post-punk and other punk related artists to the touring circuit, and their exploitation of the new Internet environment, and indeed the sonic and psychic landscape it conjures, defies the industrial logic of the record industry and its hangers-on.

Groups like Wire, Gang of Four, and others associated with the post-punk moment owe much to the fact that there isn’t much new under the sun in rock music. That is, Adorno was right in part; there are only so many combinations of notes, chords, and musical elements.2 But as popular music scholar Andrew Goodwin has pointed out, part interchangeability isn’t necessarily a bad thing.3 Since at least the 1990s if not early a lot of “new” popular music, especially that coming from the so-called indie camp, has sounded a lot like that of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The women and men who made rock in the 90s and later were likely first exposed to it because what can increasingly be called a curatorial impulse. I use the term somewhat differently than it’s sometime applied.4 A recent post in the online journal The L Magazine titled, “Is Obsessive ‘Curation’ Ruining Brooklyn,” critiques the hipster habit of compiling lists “representative of lifestyle consumerism.” Curation, to this author, is the mobilization of taste, in gummable tidbits, to signify who we are. In this formulation, it’s all surface, with no depth. I prefer a kinder, older sense of the word curation, implying culling, saving, collecting, and displaying. Granted, there are problems with that, too, especially around the pesky issue of cultural power, but done well, curated riffs, snippets and sounds can lead to a greater appreciation of the influence as well as the influenced.

Time and trends, too, have aroused a curatorial interest in some. For example, the Raincoats, along with other women in punk, were a footnote to popular music history until two developments at around the same time in the 1990s. One was Kurt Cobain’s championship of the band, a good use of his cultural power if ever there was one. Unfortunately, he committed suicide before The Raincoats could open for him in 1994. They toured anyway; I saw them at the fabled Middle East in Cambridge, Mass. I don’t remember a huge crowd, and they were booked in the smaller of club’s two bigger rooms. Their credibility as pioneering “women in rock” was still ghettoized to primarily women and punks who were there. The second was the Riot Grrrl movement that looked to the Raincoats and other female punk bands of the era for sonic and spiritual inspiration. Granted, gender relations in popular music, especially those that articulate to that increasingly meaningless term rock, still have a long way to go but they are better than they were. One of the results is a greater curiosity about female bands of the past and the filling in of missing histories and more, as well as the “years of the women” of the 1990s and the increased visibility for women in rock that resulted. Consequently, late last year, the Raincoats played MOMA—thus making curating literal. Along the way younger audiences have appeared, wanting to learn and connect to the past that the still very vital Raincoats and other groups still represent. In the sense that it helps to put or restore acts and genres to their deserved place in music history and the musical present, curating is a very good thing.

The Internet and social networking may play the most important part in destroying notions of youth music and taking the age restrictions off of music in any sense. Keir Keightley has written deftly about how age grading strategies ensured the importance of the backlog to the health of the old school music industry.5 Now, with the music industry, especially its recording part, in tatters, the Internet is enabling bands to build and recompile audiences without the industry. Clever use of social networking enables bands to communicate directly with their audiences. The Gang of Four site is an example of a deft appeal to both old and new audiences. Social networking sites Facebook, Twitter, MySpace, YouTube and a RSS feed are but a click away on each one of its pages. The band’s new recording, “Content,” (talk about a name ready made for Web 2.0) is presented in a number of formats and configurations. The well-heeled near-boomer who was in the crowd the first time around can get a “Deluxe Can, which contains a CD copy of album, an additional track, a history of the world image montage, a book of smells, a book of emotions, a book of lyrics and a vial of ‘Gang Of Four’ blood!” Obviously, they know both their fans and obsessive hipsters. The rest of us can buy the recording in CD, vinyl, or MP3 formats, straight from the website. National Public Radio in the US was streaming the recording on-line as of this writing. Granted, their strategy seems designed to target their middle-aged fans, but their address and means of communicating is catnip to the younger crowd. I expect to see quite the gamut of ages at their show.

So what is youth music in this context? It isn’t. 1979 is indeed 2011, and for the future of popular music and rock discourse, that’s a very good thing.

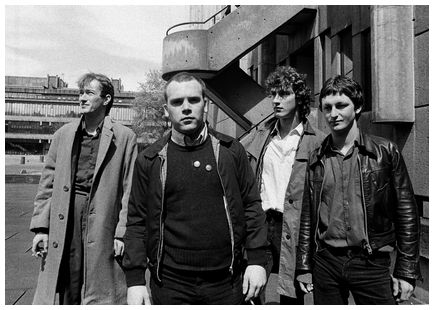

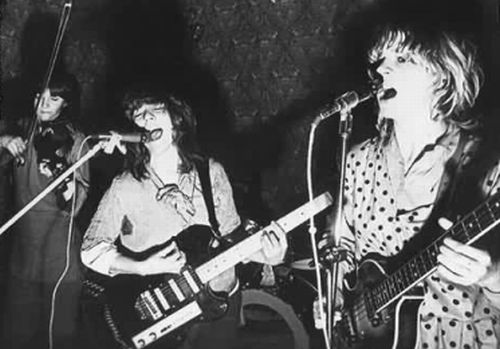

Image Credits:

1. Gang of Four then

2. The Raincoats then

3. Gang of Four now

4. The Raincoats now

Please feel free to comment.

- I am paying homage her to Daniel Marcus’s work on “the 50s in the 70s,” as discussed in Happy Days and Wonder Years: The Fifties and the Sixties in Contemporary Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004). [↩]

- Adorno, Theodor and George Simpson, “On Popular Music”, On Record: Rock, Pop and the Written Word. (New York: Routledge, 1990). [↩]

- Andrew Goodwin, Dancing in the Distraction Factory: Music Television and Popular Culture. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992), chapter 4, “The Structure of Music Video.” [↩]

- Indeed, this could be the topic of several Flow articles in and of itself. [↩]

- Keir Keightley, “Long Play: adult-oriented popular music and the temporal logics of the Post-War sound recording industry.” Media, Culture & Society, May 2004, vol. 26, no. 3, 375-391. [↩]

Thanks for the article. I think the authenticity issue is interesting because when these bands came out, the notion of performing authenticity was already a part of the music. Some punk bands (the germs, x-ray spex) embraced the blurring of real/fake and especially post-punk bands embraced that false dichotomy (minute men, slits, wire). I think it’s awesome that these bands, whose music is now being recycled by musicians as new and fresh, are at least getting some economic benefit from the mass popularity of the type of music that they first recorded.

Thanks for this really interesting article Norma. I couldn’t help but think of the ways in which bloggers (thinking here of Style Rookie’s Tavi) have also been engaging with this kind of ‘curating’ music through online media. A few months back Tavi did a really interesting post about Courtney Love that has interesting implications for (feminist) cultural (rock) icons and the ways that these figures are being passed through generations. Definitely going to share this article to my students in Mary’s Gender and Rock Culture class.

Norma – Thanks for posting this excellent article. I find it a great companion piece to your previous column.

This nostalgic return to the post-punk era that you so interestingly document seems to me to speak to a culturally broader mobilization of nostalgia for early 1980s popular culture, stemming in part, I would suggest, from a cultural need to sugar-coat the troubling larger parallels to be drawn between the early 1980s and the present period/recent past viz. the global recession that so prominently colours both eras.

With this in mind, what is particularly interesting to me about your assertion that ‘1979 is 2011’ is the apparent need for us to culturally acknowledge what has been variously discussed and referred to as a return to the early 80s in economic terms, via an equivalent discursive return and recourse to the cultural forms and expressions that evoke this time and its associations, and which can also be seen in British time travel police drama series ‘Ashes to Ashes,’ (spin-off to the conceptual forerunner ‘Life on Mars’) the premise of which sees the protagonist relive and recycle her memories of the period 1981-1983 from her 2008 (in which the UK is on the brink of similarly major recession) viewpoint. The series is littered with fondly nostalgic remembering of popular cultural ephemera of the time, as well as ambivalent critique of the socio-political context depicted, and noticeably courts the inference of parallels to the present.

UK music critic Alex Petridis of The Guardian newspaper, has been particularly attuned to this phenomenon where popular music is concerned, and he draws such recession oriented parallels by, for example, comparing the 2008 album chart success of AC/DC with the comparably recessionary context of the release of Back In Black in 1980, the success of both of which he attributes to recession era desires for simplicity and escapism: http://www.guardian.co.uk/musi.....-recession.

I wonder if the parallel you draw here between 1979/1980 and the present might also be symptomatic of recessionary culture?

What a wonderfully interesting article!

It’s really fascinating to examine how subversion can be so cyclical in the age of mechanical reproduction and how a genre that was once so subversive has managed to remain relevant through their nostalgic reinvention.

Gang of Four has really played both sides of the fence here by satisfying their original fanbase while laying claim to street authenticity and attracting a new hipster crowd. Perhaps most interesting is the band’s decision to have the album streaming for free, while also being released on CD, iTunes and on vinyl – the true marker postmodern irony – but also the mysterious additions in the “Deluxe Can,” retailing for around $70 USD which promises a new level of Benjaminian aura for the true fan.

What can be more nostalgic than an art piece by Jon King and Andy Gill “depicting the last 40 years of world history,” a scratch-and-sniff book of smells, and “a “book of drawings of our emotions”? If you can’t be there to experience it, why not enact your nostalgia through this veritable all-encompassing sensory recreation?

But truly, the icing on the cake is the vials of blood from the King and Gill which, according to Pitchfork, have been confirmed to be their actual plasma. In the age of mechanical reproduction, is the new aura not just seeing the band, but actually owning a piece of them?

our article was really interesting! I find that the new health care bill is very interesting and you really explained it well. I am a fan of this website and I will come back again. Thanks for taking your time to write suc a great article and inform all of us.

Thanks for the article. I think the authenticity issue is interesting because when these bands came out, the notion of performing authenticity was already a part of the music. Some punk bands (the germs, x-ray spex) embraced the blurring of real/fake and especially post-punk bands embraced that false dichotomy (minute men, slits, wire). I think it’s awesome that these bands, whose music is now being recycled by musicians as new and fresh, are at least getting some economic benefit from the mass popularity of the type of music that they first recorded.

What can be more nostalgic than an art piece by Jon King and Andy Gill “depicting the last 40 years of world history,” a scratch-and-sniff book of smells, and “a “book of drawings of our emotions”? If you can’t be there to experience it, why not enact your nostalgia through this veritable all-encompassing sensory recreation?