“Asian Enough”: Race, Nation and Misrepresentation

Konrad Ng / University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

Canada’s Maclean’s magazine’s annual review of the nation’s post-secondary institutions included a piece entitled “‘Too Asian?’ Worries that efforts in the U.S. to limit enrollment of Asian students in top universities may migrate to Canada.”1 The article sought to explore the “tough question” of considering instances when a Canadian university’s system of meritocratic admissions “risk[s] becoming too skewed one way, changing campus life” because of a specific racial group: “Asians.” Authors Stephanie Findlay and Nicholas Kohler begin with a quote from an anonymous graduating high school senior who preferred a university experience that would not be a “killjoy”—that is, a school with “‘a ‘reputation of being Asian.’” According to Findlay and Kohler, for white Canadian students like “Alexandra,” a school’s reputation of “being Asian” means an intense level of academic rigor, social monasticism and cultural Balkanization. Findlay and Kohler use Alexandra’s experience to illustrate how a high Asian population has become “a cause for concern to university admissions officers and high school guidance counsellors” and, they assert, a reason to limit Asian enrollment in some U.S. universities. “Too Asian” echoed a similar work by Canadian television journalism program W5 that aired in 1979. W5’s “Campus Giveaway” reported how Chinese students were preventing Canadians from enrolling in university programs. However, the report omitted the fact that the “Chinese” depicted in the piece were Canadian citizens and in general, “Campus Giveaway” overstated the issue. I open with Maclean’s and W5 because they both invoke stereotypes familiar to Americans and Canadians of Asian descent—model minorities, alien to the country of citizenship, and part of a threatening “Yellow Peril”—that continue to obscure lived experience. The sins of Maclean’s and W5 are similar to the xenophobia that emerged during the recent 2010 U.S. midterm elections. China became a common scapegoat in campaign ads yet there was a persistent failure to make important distinctions between China and Asian America.

What shapes our representation of Asian-ness? To examine the politics of Asian representation in America and Canada offers a way for understanding how race is a discursive—as opposed to a natural—formation that reflects biopolitical exercises of power and enfranchisement. While there is ample work being done in critical race discourse and Asian-ness, W5, Maclean’s and the 2010 midterm campaign commercials suggest that vigilance and continued activism remains necessary. As such, how might we shape the representation of Asian-ness? How might we engage in a more complex and critical visual language for Asian American and Canadian identity? As Elaine Chang notes about the critical dimensions offered by the study of Asian Canadian cinema:

What does becoming visible really, fully mean and entail? To ask these sorts of questions need not necessarily be to fall back on preconceptions of an enduring and essentialized identity prior to the image’s capacity for distortion, to demand more of the ‘positive representations’ of an ethnic/racial or cultural minority group that Yung quite accurately notes are often boring to watch and straightjacketing to create. It can be to inquire into some of the precise ways and means of showing, telling and seeing that constitute the mechanisms of local and global visibilities.2

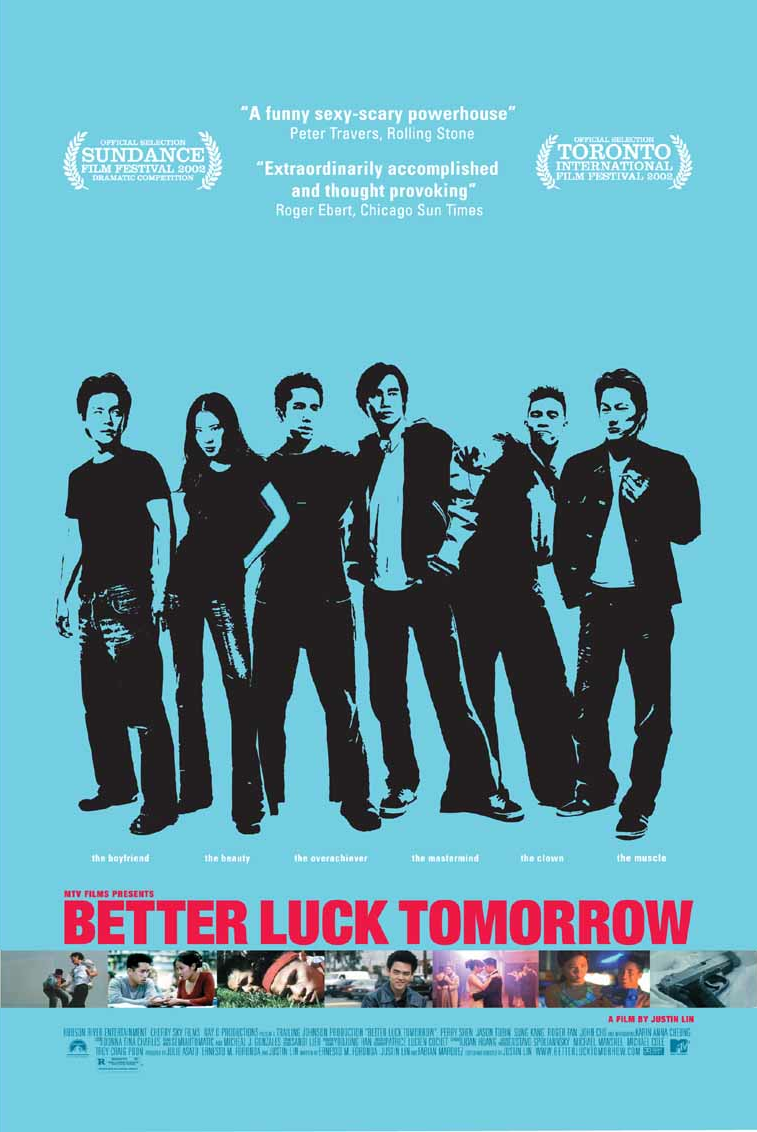

I want to return to Justin Lin, a filmmaker whom I have discussed in a previous column. “Too Asian” reminds me of how Lin’s film, Better Luck Tomorrow (2003), critiques the stereotypes promoted by the Maclean’s article. Better Luck Tomorrow was nominated for awards at the Sundance Film Festival and the U.S. Independent Spirit Awards and was the first feature film acquired by MTV film division. The film is about how a group of suburban Asian American high school seniors use Asian American stereotypes as a cover for their illicit activities. The main characters earn straight-As, hold jobs, participate in high school sports and clubs, compete in academic decathlons, perform public service and have applied to Ivy League schools. Although their outward appearance personifies the model minority image, the characters use the stereotype to cover their cheating, stealing, drug trafficking, sex, violence and murder. The main character, Ben, states, “Our straight As were our alibis, our passports to freedom. Going to study group would get us out of the house until four in the morning, as long as our grades were there, we were trusted, we had it all.” Eventually, the group’s collective desire to “buck the system” leads to their self-destruction but any sense of personal development is denied by the film’s ambiguous ending. Ben dismisses the deadly events of his senior year as a “learning experience” and decides to focus on attending university and the budding relationship with the girl whose boyfriend he murdered.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bf9q7twWZlc[/youtube]

While the story takes aim at Asian stereotypes, the complexity of the film’s visual language is worth noting; Better Luck Tomorrow frames how the discourse of the model minority confines Asian representation in the West while simultaneously suggesting dissent. For example, the film’s mise-en-scene and cinematography uses the idealized space of suburbia to locate the story within a space primarily known for its orderliness. The opening scene is of a gate opening to a suburban community. The predominant backdrops are schools and playgrounds enclosed by fences with a majority of the action within or behind fenced areas. Additionally, the characters are framed tightly, at the edge of the frame, occupy the entirety of the frame or are blocked in crowded spaces. These aesthetics of confinement convey a feeling of claustrophobia and helps set the tone for the motivation to change from being “model minorities” into criminals. The aesthetic of confinement continues throughout the film while the narrative dictates a descent that accelerates into a freefall. At the point when the characters begin their crash, Lin employs aesthetic choices like the extensive manipulation of image speed, jump cuts and increased cutting to create a disorienting and alienating experience. The effect of the aesthetics of confinement and discontinuity creates a visual grammar whereby Asian-ness is a volatile agency and resists the damaging simplicity of the model minority stereotype.

A film like Better Luck Tomorrow circulates representations that counterbalance images that continue to inform pieces like “Too Asian.” These alternate portrayals of Asian life in the West do not reflect reality or aspire to do so. Rather, the film participates in a politics of misrepresentation that crowds the popular imaginary with conflicting images and by so doing, the film adds complexity and consciousness to the understanding of Asian-ness. In other words, the critical worth of Better Luck Tomorrow is its ability to add work to the activity of social understanding; viewers are encouraged to determine the accuracy and value of the imagery in circulation. Indeed, the possibility of films like Better Luck Tomorrow is how the conceptual labor added to the act of understanding a more populated visual field will encourage the media’s depiction of Asian American and Canadian life in more complex terms.

Image Credits:

1. Author’s screen capture.

2. © 2003 MTV Films. All rights reserved.

3. Author’s screen capture.

Please feel free to comment.

- For more background, please see Henry Yu’s “Why Macleans and racism should no longer define Canada,” Georgia Strait, November 16, 2010, http://www.straight.com/article-358546/vancouver/henry-yu-why-macleans-and-racism-should-no-longer-define-canada (accessed November 16, 2010) and “Macleans offers a nonapology for writing a nonstory called ‘Too Asian?’,” Georgia Straight, November 17, 2010, http://www.straight.com/article-361680/vancouver/henry-yu-macleans-offers-nonapology-writing-nonstory-called-too-asian (accessed November 27, 2010). [↩]

- Elaine Chang, Reel Asian: Asian Canada on Screen, Toronto: Coach House Books, 2007, 19. [↩]

Insightful points into the connections between representative imagery and popular discourse. Your article made me wonder just how prominent some of these issues may be in university systems across North America. The publications and ads you discuss appear to be emerging out of the same vein of discourses as those in recent trends in conservatism, and “a more populated visual field” seems necessary in not only the cinematic landscape, but also the political landscape. Hopefully more complex imagery will find greater distribution in mainstream media avenues.

Pingback: Better luck tomorrow | FinAppx