Everybody Knows

Charles R. Acland / Concordia University

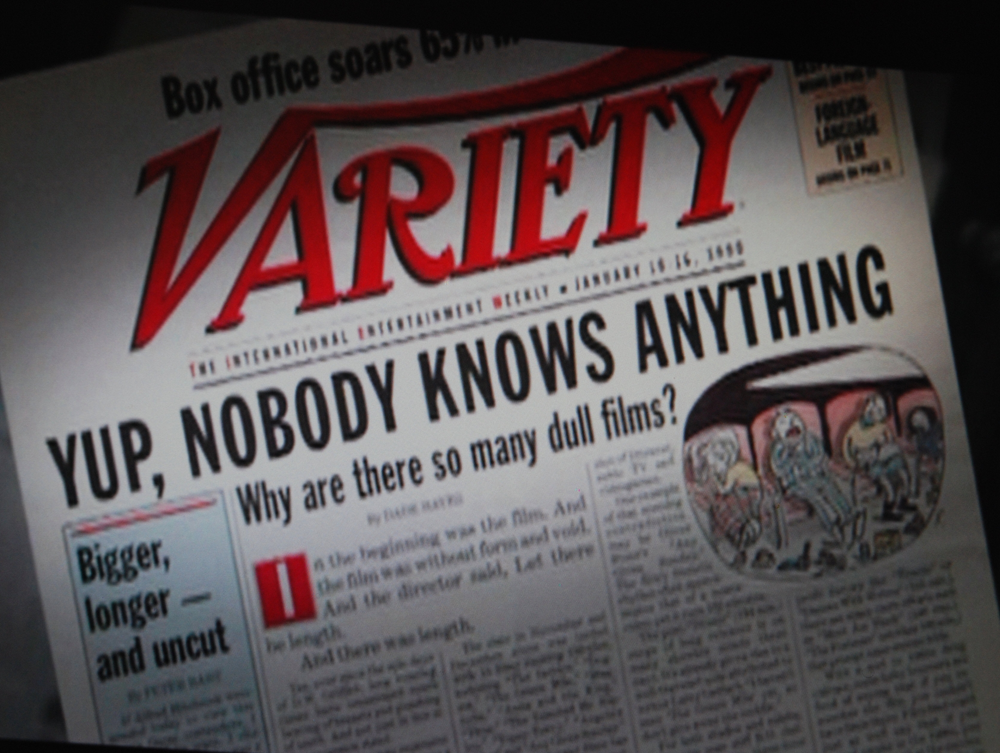

“Nobody knows anything” segment of

Boffo!: Tinseltown’s Bombs and Blockbusters1

There it is again. Like the Wilhelm Scream (“ah-AAA-ah”) sound effect, used so frequently that it has become an inside joke among sound designers and movie buffs. Or like that stock footage of a monkey washing a cat, played regularly by David Letterman and Jon Stewart on their shows, footage that is familiar and inconsequential, and references little other than its own apparent inconsequential familiarity. There it is, the most reflexively invoked aphorism about Hollywood: “Nobody knows anything.”

My most recent sighting was in the lead film article of a recent issue of Variety (September 6-12, 2010), but one doesn’t have to root around trade and entertainment news very long before you bump into this statement. More than journalistic shorthand—though it is that—it is equally likely to be uttered by producers, directors, actors, and critics. The HBO documentary, Boffo!: Tinseltown’s Bombs and Blockbusters, based on a book by Variety editor Peter Bart, devotes an entire segment of its short 75 minute running time to various celebrity insiders—among them Morgan Freeman, George Clooney, and Sydney Pollack—commenting on the accepted truth that nobody knows anything in Hollywood. In a virtually Rumsfeldian way, people in Hollywood may not know anything, but they know they know nothing.

Those repeating the “nobody knows anything” line tend to acknowledge that it is legendary screenwriter William Goldman’s acerbic assessment of Hollywood decision-making. So its repetition and attribution are a sliver of an industrial culture of citation, which, in and of itself, is intriguing. Respect for authorship and its particular creative labors, let alone the tribute of quotation, are hardly prominent features of our time. The routine incantation of Goldman’s bottom-line slogan as his slogan is recognition that it comes from an experienced and perceptive wit, and perhaps most importantly, from someone who is a critical and financial winner in the Hollywood game. Pierre Bourdieu tells us that there is no more powerful marker of cultural capital than the ability to bestow value where there is perceived to be none. Similarly, there is no more extreme exercising of meritorious status than to reveal the lie of meritorious status. Goldman’s career has earned him a position in which he can legitimately say there is nothing to earn, and still get work at good pay when he wants it.

“Nobody knows anything” is Goldman’s conclusion after years of witnessing haphazard decisions made by studio executives, who seem to be guided by sheer luck and blind impulsiveness. The line appears in his 1983 book Adventures in the Screen Trade, in which Goldman rehearses amusing behind-the-scenes stories about productions of his scripts, including Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All the President’s Men. In his low estimation, studio executives simply have no idea what will work in a film and what will click with audiences. To demonstrate this he recites examples of people making good decisions against their better judgment (e.g. after a preview for Butch Cassidy, B.J. Thomas’s representatives complained that the singer had set back his career by doing “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” for the film), people predicting success for weak properties (e.g. Richard Zanuck thought he would have a bigger hit than The Sound of Music with Star!), and people making risk-adverse decisions about movies that will prove to be lucrative for someone else (e.g. every studio except Paramount turned down Raiders of the Lost Ark, even with hit-makers Steven Spielberg and George Lucas attached to the project).

In its debut, Goldman builds up his one-liner as a core axiom of the Hollywood business scene. In fact, so no reader can misunderstand how fundamental this claim is, it actually appears on its own in the middle of the page as “NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING,” which he then repeats in the same format a few lines later. It’s like Goldman is shouting it at you. The phrase has since traveled far since its first appearance, leaving behind Goldman’s book, crammed as it is with amusing anecdotes. One almost never hears, for instance, that “nobody knows anything” was one of two core axioms suggested by Goldman in that book, the other being “SCREENPLAYS ARE STRUCTURE,” which he introduces with the same format and repetition as the first more famous one. No surprise that screenwriter Goldman places his craft at the heart of the movie-making enterprise, nor that, in the context of the hegemony of scriptwriting authority Syd Field and now of Movie Magic Screenwriter software, the logical segmentation and organization of events and tasks is taken as a primary function of scripts. What is striking is that as a key to the secrets of Hollywood, “screenplays are structure” has been left aside for the more generalizing claim that “nobody knows anything.”

Surely, part of the appeal of that oft-repeated line is its irreverence. It conveys the impression that one doesn’t take one’s profession too seriously. It is self-effacing and blasé, and in this way, it express a sense of cool. Giving credit to chance, the statement humbles. Importantly, it turns the reins over to the audience, whose wild nature makes them unpredictable and unknowable to industrial agents. “Nobody knows anything” flatters the popular movie-goer as a dignified and mystical energy that can never be captured by the mere ambitions of showman, unless, of course, we want to be captured.

This, of course, is classic mythmaking. These are stories one segment of the media industries tells in order to smooth over obvious and material contradictions, like why some marginally inventive people have long and illustrious careers and other more talented folks languish on the sidelines. The “nobody knows anything” catch-phrase is smokescreen, pure and simple, for an extensive and concentrated organization of advantage in the arena of commercial cultural enterprise. This advantage is evident in terms of access to capital, the ability to act on the rising and falling value of talent, the existence of deep-pockets for industrial-size audience research, the ownership of prized intellectual property, and a corporate structure that facilitates cross-media launches of new franchises. In other words, a good deal of time, resources, and effort are devoted to the accumulation of knowledge useful to the cultural industrial operations and to the protection of the ability to capitalize on that knowledge.

The “nobody knows anything” thesis is a bid to present the corridors of cultural finance and industry as an art world, ruled by passion and inspiration. There is something appealing, if disingenuous, about our treasured artists—Morgan Freeman, George Clooney, and Sydney Pollack—as hapless creatures of whim. Still, contra the protestations of ignorance, as Leonard Cohen sings it, “Everybody knows the dice are loaded.”

Image Credits:

1. Frame grab from Boffo!: Tinseltown’s Bombs and Blockbusters (HBO, 2004)

2. Frame grab from Boffo!: Tinseltown’s Bombs and Blockbusters (HBO, 2004)

3. Screenplay

4. Audience

Please feel free to comment.

- Bill Couturié, 2004 [↩]

It was interesting that the term “nobody knows anything” could go both ways; the audience has the power to decide which films to what and that would decide the fate of the film or that the creative industries (and other external forces) are the deciding forces of the success of the film.

Also, I was wondering why Goldman’s other saying; “screenplays are the structure” was not as widely known. Do you have any thoughts about why this phrase didn’t get quite as popular as the “nobody knows anything” phase?

Great bit of organizational sociology, suggesting the functionality of the “nobody knows” trope in supporting the power pyramid of entertainment capital. Thanks.

Pingback: Knows What It Knows | AllGraphicsOnline.com