“The future, Mr. Gittes. The future.”: Next Wave Filmmaking and Beyond, Part 1 *

Robert Sickels / Whitman College

Rather than trying to make low budget versions of high-end Hollywood films, many contemporary young filmmakers are instead ignoring the commercial marketplace and making the movies they want to make on their own terms. At the forefront of these filmmakers are folks like Andrew Bujalski, Joe Swanberg, Aaron Katz, and Mark and Jay Duplass, who are considered founders of and key players in the so-called “mumblecore” movement, even though they uniformly find the moniker “reductive and silly”.1 There is far from consensus as to the value of their work, but much of the extant criticism is misplaced and focuses too much on what they’re doing in comparison to Hollywood and not enough on how they’re doing it, as it’s the how that may ultimately prove to be much more influential.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_DYbMPmG28[/youtube]

“Mumblecore” is a terrible name for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the way it has been pounced on by its detractors, who use the term derisively to emphasize what they see as its shortcomings. Take, for example, Amy Taubin, who asserts that “[o]n a technical level, these are micro-budget movies where sound is almost always a neglected element.”2 While the technical acumen isn’t always in the same league as a studio production, the sound is fine and regardless, I’d argue the term is less about sound quality then it is the way the characters talk, which is in halting, elliptically clipped phrases, full of the “ums,” “you knows,” and “likes” that are the lingua franca of the twenty-somethings these films typically feature. The inarticulateness is representative of an inability or unwillingness on the part of the characters to connect with one another on an emotional level that goes beyond their normal superficial but safe mode of communication.

While there are differences in the work of these directors, there are some unifying elements as well. Most of them shoot on digital video and there are a lot of long hand held shots. Part of this is aesthetic, but functionality and financial imperatives play a role too. With small, often non-professional casts and crews that are donating their time, it’s easier to do longer, uncomplicated shots. While the shots are simple, the editing often isn’t, in that there are frequently arrhythmic cuts, resulting in an unsettling effect on the viewer. Additionally, they tend to be more open to improvisation than most filmmakers. The reasons for this are also as much financial as they are aesthetic. Because they often get their friends to act (and crew and create the music, etc.) and typically shoot on digital video the only extra cost improvisation incurs is time, which, as they aren’t paying union rates for cast and crew, doesn’t translate to monetary cost in the same way that shooting extra footage does on a studio production. And, as Taubin writes, “. . . these non-actors are perfect choices for these films because their insecurity and embarrassment about voicing their characters’ ideas, desires, and feelings . . . dovetails with a defining characteristic of the particular cohort (white, middle-class, twenty-something) to which the filmmakers and their quasi-fictional characters belong. The mumblecore films literally speak in the voice of that cohort, and the best of them do so with remarkable and revealing precision.”

The subject of these films frequently centers around the characters’ “quarterlife crises,” which accompany the difficulty many post-grads have in transitioning from college to the working world. Dennis Lim evocatively describes this period as “the blurry limbo of post-collegiate existence, a period at once ephemeral and cruelly decisive” (commenting on “The Graduates”).3 This focus on post-college malaise has resulted in these filmmakers being dubbed the “voices of their generation,” a sobriquet with which they are justifiably uncomfortable, even while they acknowledge the possibility. As Bujalski posits, “‘fear of adulthood is a theme that pervades [my] films . . . and . . . maybe that is something that is specific, if not to ‘my generation,’ then at least my subset of it. I feel like a lot of people I know, myself included, are still figuring out what we’re doing, are single and so forth, even though we’re now at a point where we’re older than our parents were when they married and had us’”.4

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VYpxFXBf1g[/youtube]

But even if one views the term “mumblecore” as being more about the emotional stuntedness of its characters than a snide reference to its perceived technological deficiencies, it’s still a rotten term that doesn’t do the importance of the work justice. In describing the current state of independent cinema John Patterson claims that the “last independent generation has been co-opted by the studios, and the next one still labours in digicam/web-based/mumblecore obscurity, with its auteurs and iconoclasts yet to establish themselves.”5 Again, the idea that these filmmakers are working in “mumblecore” is derogatory in that they’re simply marking time until they get to the big league of Hollywood cinema. But what’s important to take from this is that many of them are going to eventually make their way to Hollywood; they are the next wave of filmmakers, and that’s exactly what they should be called: Next Wave filmmakers. There’s a lot of contention over whether or not the work of these filmmakers to date comprises a genre. David Denby refers without comment to “a recent genre of micro-budget independent movies,”6 whereas Taubin argues that mumblecore was “never more than a flurry of festival hype and blogoshpere branding” and definitely not a movement in “the grand sense of the French New Wave or the postwar American avant-garde.” While I don’t think the collective output of the Next Wavers comprises a genre, I do think there’s no doubt that a movement is afoot and history may well prove it to be every bit as grand as those Taubin cites. In fact, the French New Wave is a particularly apt analogy, in that it included a bunch of different filmmakers making a wide array of movies. The variance of their output prevented their being generically categorized, but the fact that they were making movies at the same time and that their work, often funded by the French government, was an anarchical alternative to mainstream European cinema is what made it a movement.

Kim Masters describes the output of Next Wave filmmakers as simply being “made with tiny budgets, shot on hand-held digital cameras, with unknown actors who talk a lot about their lives.”7 While true, there is more to their work than broad similarities that could just as accurately describe most home movies. In fact, there is a lot more narrative unity among the output of Next Wave filmmakers than there ever was among New Wave filmmakers. As Lim notes, “. . . what these films understand all too well is that the tentative drift of the in-between years masks quietly seismic shifts that are apparent only in hindsight. Mumblecore narratives hinge less on plot points than on the tipping points in interpersonal relationships . . . . Artists who mine life’s minutiae are by no means new, but mumblecore bespeaks a true 21st-century sensibility, reflective of MySpace-like social networks and the voyeurism and intimacy of YouTube.”8

The press has done a lot to pigeon-hole Next Wave filmmakers, in no small part because they typically focus on Bujalski, Swanberg, Katz, and the Duplass Brothers, which makes it seem more like an exclusive fraternity than a broad scale movement. Taubin is absolutely right when she taps Korean American filmmaker So Yong Kim as deserving inclusion in what I call the Next Wave movement. I would put Kelly Reichardt in this group as well. In fact, there are a ton of young Next Wave filmmakers of all colors, genders, and sexual orientations who are embracing the freedom and opportunity that comes with low budget filmmaking, digital or otherwise, and some of them will definitely break through and make their marks as filmmakers. The club as touted by the media is small, but that’s not reflective of the groundswell that’s taking place in the world of filmmaking right now. To wit, in the winter of 2010, the Sundance Film Festival included a new section that featured low and no budget films, tellingly titled “Next.” Eight films were selected for Next, all of them shot on digital video by a multi-ethnic array of directors who range in age from 24 to 32.9 While not identified as part of the “mumblecore” gang, there’s no doubt they are all working in the same ballpark. In “A Generation,” Lim writes that Next Wave filmmakers are part of “[m]ore a loose collective or even a state of mind than an actual aesthetic movement,” but I would argue that they are at the forefront of a revolutionary technological movement that will undoubtedly have profound long term effects on the industry. Add to that the fact that they are much more open to change and new methods than their elders, and it seems inevitable that they will play a role in the future of Hollywood. It’s not “if,” it’s “when.”

*This essay stems from a chapter on Next Wave filmmaking that will appear in American Film in the Digital Age, forthcoming from Praeger Press in November of 2011. http://www.praeger.com/catalog/C9862.aspx

Image Credits:

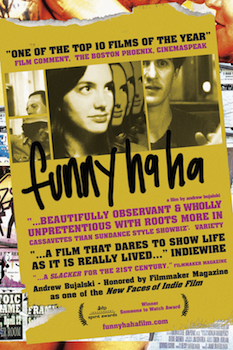

1. Funny Ha Ha poster

2. Still from Mutual Appreciation

- Koresky, Michael. “The Mumblecore Movement? Andrew Bujalski on his ‘Funny, Ha

Ha.’” Indiewire.com 22 August 2005. [↩] - Taubin, Amy. “All talk? Supposedly the voice of its generation, the indie film movement known as Mumblecore has had its 15 minutes.” Film Society of Lincoln Center.com November/December 2007. [↩]

- Lim, Dennis. “The Graduates: Indie Captures Twentysomething Indecision, Like, Perfectly.” The Village Voice.com 19 April 2005. [↩]

- Foundas, Scott. “Mutual Appreciation Society: The World of Andrew Bujalski.” LA Weekly.com 7 September 2006. [↩]

- Patterson, John. “The Last Indie Film Generation has been Co-opted by the Studios, While the Next Still Labours in Digicam, Mumblecore Obscurity.” The

Guardian [London].com 18 July 2008. [↩] - Denby, David. “Youthquake: Mumblecore Movies.” The New Yorker.com 16 March 2009. [↩]

- Masters, Kim. “The Brothers Duplass Go Studio.” KCRW’s The Business Podcast 21 June 2010. [↩]

- Dennis Lim. “A Generation Finds its Mumble.” The New York Times.com 19 August 2007. [↩]

- Wood, Jennifer M. “Sundance’s ‘Next’ Wave of Indie Moviemakers.” Moviemaker.com 19 January 2010. [↩]

Thanks for writing about these newer filmmakers. The films I’ve seen, seem to be made by filmmakers fully engaged in the full range of film history and theory, as well as artistic practice, instead of focusing on narrative-film-as-product. One thing that I’ve noticed reading critics that focus on the supposed lack of production values in independent films, is that the authors treat the aesthetic choices (shaky camera, minimally processed sound and image, etc.) as if they were a mistakes.

Nestor,

Thanks for the comment. I couldn’t agree more. Too often the extant criticism assumes like folks think these filmmakers are just young kids that don’t know what they’re doing, and that’s just not the case. They definitely know their craft and could easily make their work more appear more polished if they wanted to, but they are making choices for a reason, just as Godard did in Breathless. At the time a lot of folks were annoyed by all the jump cuts in Breathless, but its influence is pretty clear today. It’ll be interesting to see how the work of this group of filmmakers is considered in the future.