On Retrospective Reception: Watching LVN Pictures at the Cinemalaya Film Festival

Bliss Cua Lim / University of California, Irvine

One of nine films in the 2010 Cinemalaya Film Festival’s retrospective exhibition of LVN studio classics,1 the 1961 crime thriller Sandata at Pangako (Weapon and Promise, dir. F.H. Constantino) was made at the threshold of the old and the new. Sandata was LVN Pictures’ last release and its only film featuring action icon Fernando Poe, Jr. (“FPJ”), the wildly popular box office king whose decision to break his studio contract in favor of independent producers’ larger talent fees heralded the studio system’s demise.2

The enthusiastic audience at Cinemalaya’s retrospective screening of Sandata had come for a glimpse of the late star in his youthful glory, but we left savoring other pleasures: the technical polish of a well-made studio film and the bright-eyed, incandescent “screen personality” of multi-awarded actress Charito Solis, cast alongside the legendary FPJ. (The action king was rumored to have been her first real heartbreak).3

At the end of the screening, a college student filing out of the theater remarked—“We should have just watched all the LVN films!”4 —confirming that Cinemalaya, known for fostering independent filmmaking, is also creating an audience of young film buffs eagerly rediscovering older films.5 This emerging cinephilic encounter results in a horizon of retrospective reception that counters easy dismissals of studio era films as hackneyed formula pictures made solely for profit. More importantly, moviegoers who may have come to see how familiar stars once looked end up discovering how familiar places once looked as well: a registering of historical time inscribed in the Philippine cityscape of the forties, fifties, and sixties. This is cinematic remembering, one enabled by the archive.

Established in 1938, LVN was among the Big Three studios whose output accounted for 65% of the films produced from 1946 to 1960, a period roughly coextensive with the Golden Age of Filipino filmmaking.6 The commercially profitable star vehicles crafted by executive producer Doña Sisang7 at LVN were an admixture of nationalism, commercialism, and escapism. Director Lamberto Avellana recalls her saying, “Why remind audiences of their hardship?”8 Studio era escapism was most often achieved by predictable happy endings. Yet in Gregorio Fernandez’s 1955 melodrama Higit Sa Lahat [Above All]9, the obligatory narrative resolution is undermined by the film’s trenchant critique of postwar materialism.

Based on a serialized radio play, Higit pursues the tragic consequences of the idea that money is the highest expression of love. The film’s critique of the emptiness of the postwar culture of acquisitiveness comes through in an early scene when Roberto (studio icon Rogelio de la Rosa) and his wife Rosa (Emma Alegre) go window shopping in Manila. If the similarity between cinema screen and department store window rests on their ability to sell the pleasures of the gaze to consumer-spectators,10 then the onscreen shop window in Higit attempts to do the reverse, exposing the moviegoer’s complicity in conspicuous consumption.

When an accidental fire razes the warehouse, everyone concludes that Roberto is dead, despite the fact that he was not killed in the fire. Deciding that the windfall from his life insurance would give his family the future he could not otherwise provide, Roberto embraces self-imposed exile from his family. The intricately plotted story forces Rosa to mourn her living husband thrice over: first, when his necklace is found among a co-worker’s remains; second, when his wallet and a family picture are discovered on the person of a dead thief; and lastly, when Rosa spots him being run over by a car. When the dust from the near-collision clears, Roberto and his family are reunited at last. People are more important than money, Rosa maintains throughout the film, but Roberto is convinced that providing for his loved ones is more important than being with them (his situation is chillingly prescient of the conundrum of overseas Filipino workers today, who are forced to leave their families in order to sustain them).11

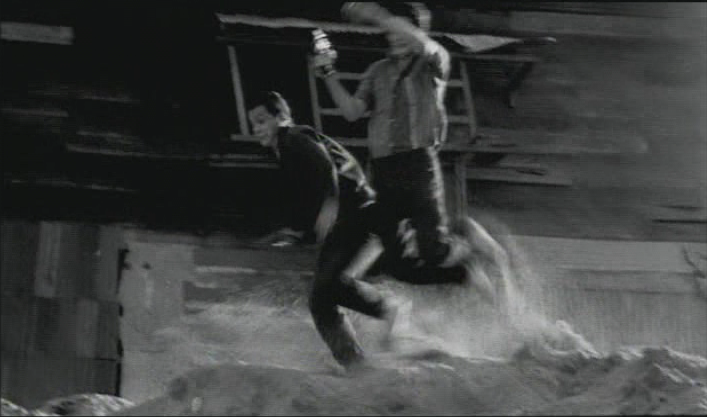

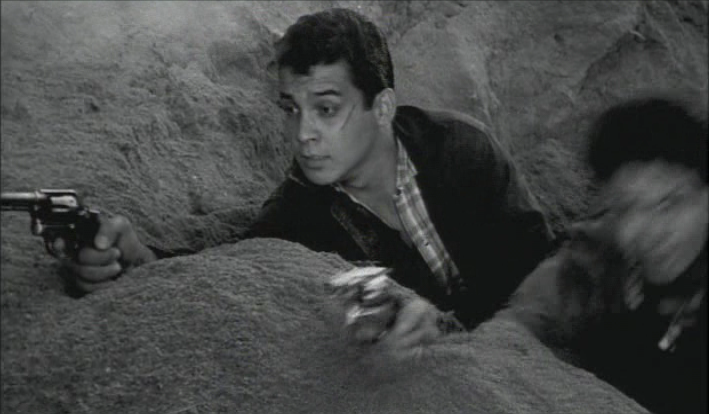

Like Higit, Sandata also contests dismissals of LVN as churning out nothing but “antiseptically rigid”, “wholesome” films. The film’s plot centers on organized crime, drug addiction, and pedophilia, surprising present-day spectators expecting a stereotypically “chaste” studio product. The plot traces a hapless couple’s involvement with a crime syndicate: Mando (FPJ), an ex-gang member, successfully helps his sweetheart Dolores (Charito Solis) overcome drug addiction.

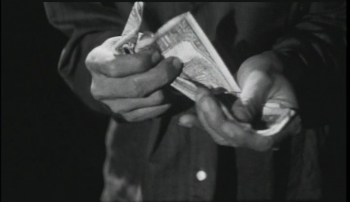

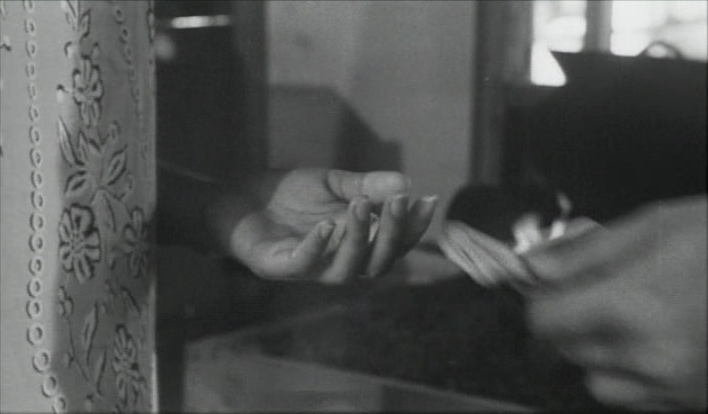

Scene transitions are conspicuously marked by graphic matches, dialogue bridges, and matches on action. In one effective transition, a match on action across two scenes underscores the thematic of filthy lucre.

The numerous editing flourishes ended up eliciting laughter from the Cinemalaya audience, whose campy response signaled not ridicule but affection.12 At one point, a form of call and response among Sandata’s viewers seemed to be taking place, with comments by a group of girls in the front of the theater provoking good-natured replies from spectators in the rear. Affectionate laughter greeted the action king’s impossible action feats as well.

Watching LVN films several decades after their initial release invites a retrospective horizon of reception. More than camp enjoyment, retrospective reception also provokes a spatial sense of the uncanny, as evident in another narratively gripping and technically polished Gregorio Fernandez film, Kung Ako’y Mahal Mo [If You Love Me, 1960].

A spurned suitor’s attempted rape of Lydia (Charito Solis) along Highway 54 is foiled when Ramon (Nestor de Villa) responds to Lydia’s cries for help. In the ensuing scuffle, Lydia drives off, so Ramon is alone when the villain inadvertently shoots himself. In the absence of the woman he claims to have saved, the police disbelieve Ramon’s protestations of innocence. His worsening plight at the hands of the justice system is intercut with shots of an impeccably dressed Lydia en route to her flight to the US the next morning. In an LVN version of the vanishing lady motif,13 Lydia’s failure to appear results in an innocent man’s conviction. Years later, unaware of their shared past, socialite and mechanic fall in love. Delayed revelations dilate the plot’s progression towards the inevitable happy ending, when all is forgiven and the lovers are reunited at last.

For contemporary viewers, scenes of the lovers against the backdrop of Balara are unexpectedly startling. When Ramon says of Balara, “The sights here are beautiful!”14 the scene triggers a kind of spatial uncanny, an unfamiliar, because forgotten, evocation of familiar urban space.15 I was amazed by Ramon’s line because I went to high school near Balara and remember it as a bustling jeepney stop and the far from scenic site of the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS).16 My mother recalls Balara as an idyllic picnic spot in the late forties; in Fernandez’s 1960 film, it is a scenic resort.

In Kung Ako’y Mahal Mo, the LVN logo and opening credits are superimposed over a crane shot of Highway 54, site of Lydia’s rescue by Ramon. For contemporary viewers, however, Highway 54 is best remembered as the pre-sixties name for Metro Manila’s most vital artery, E. de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). Today, EDSA’s north- and south-bound thoroughfares are crammed with cars, people, buildings, and billboards. Onscreen, Highway 54 in 1960 is above all a long dangerous stretch of darkness, the undeveloped real estate between Guadalupe and Buendia, notorious in the fifties for roadside robberies.

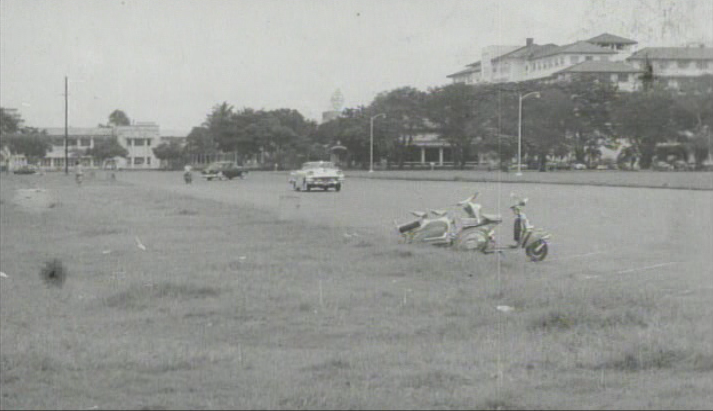

Footage of Ramon and Lydia driving around Luneta Park along T.M. Kalaw inspires an uncanny sense of spatial recognition, of presence and absence. To the right rear of the 1960 shot is the Manila Hotel, built in 1909. In the left rear is the Manila Army and Navy Club, built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1911 along Luneta on Dewey (renamed Roxas Boulevard in the sixties). Invisible, offscreen and to the left of the frame, would have been the now-abandoned Luneta Hotel, built in 1918; most strikingly, the expansive, grassy foreground in the lower left of this 1960 shot calls to mind the same spot today: a tangle of condominiums and storefronts, a Shell gas station and a 7-Eleven among them.

For Vivian Sobchack, the inscription of history in film is not metaphoric but literal: in her well-known analysis of film noir, history inheres to the visible places of the story world, the “concrete locality” of the mise-en-scène.17 In these LVN films, the visibility of historical time as place is owing to location shooting: the orderly expanse of Baguio’s Burnham park in Susana de Guzman’s Sumpaan [Vow, 1948]; Balara and Luneta in Kung Ako’y Mahal Mo. The pleasures of the archive are to be glimpsed not only in the faces of stars as they once looked but also in the forgotten visage of the Philippines’ urban iconography.

I am grateful to Vicky Belarmino and Nestor Jardin for graciously agreeing to be interviewed for this piece. This essay was made possible by the place-memories of my mother, Dr. Felicidad Cua-Lim, and the spatially-attuned cinephilia of Joya Escobar. This is dedicated to both of them, with profound thanks.

Image Credits:

1-11. Author Provided Screencaptures

Please feel free to comment.

- According to CCP film archivist Vicky Belarmino, she and film historian Nic Tiongson chose the films for the Cinemalaya LVN retrospective from a dozen relatively well-preserved LVN titles with good image and sound quality (see my prior Flowtv.org column on the archive crisis in Phlippine cinema.) They adopted the following criteria in choosing nine films for the retrospective program: good copies must be available in digital format; the titles must be rarely exhibited; and the program as a whole must comprise a mix of genres. Personal interview with Vicky Belarmino, July 23, 2010. [↩]

- Coincidentally, FPJ’s father, Fernando Poe, Sr., starred in LVN’s very first film, Giliw Ko [My Darling, 1939]. Two years after FPJ broke his contract with mother studio Premiere Productions in 1960, he founded his own production company, ushering in the post-studio trend of independent superstar-producers. The decline of the studio system meant that by 1965, a handful of top stars were getting paid six times their normal asking price in comparison with their usual fee in 1960; the film industry as a whole was producing almost 200 films a year, double the annual number of films produced in the studio era. See Ross F. Celino. “Busiest Stars of 1965.” Weekly Graphic 32, no. 28 (January 5, 1966): 38-39; and “Sandata at Pangako (1961)”, http://fpj-daking.blogspot.com/2008/09/sandata-at-pangako-1961.html

FPJ’s film career began in the mid-1950s and spanned almost five decades; he was a contender in the 2004 presidential elections but was defeated by Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. FPJ is widely believed to have won more electoral votes than Arroyo, but Arroyo was never impeached despite proof of her direct involvement with large-scale vote tampering. [↩] - According to Baldovino, Charito Solis received twelve acting awards and thirteen nominations over the course of a forty-three year career in movies. As a young actress, Solis was quiet and introverted, despite the “incandescence that showed in her eyes”. (Tirol, 46) She possessed what LVN studio chiefs called a “screen personality”, “that indefinable ‘something’ that causes the audience to rivet its attention” on her. (Torre, 11) See Gypsy Baldovino’s two-part article, “Charito Solis: Empress of Drama,” and “Charito Solis: a Tough Act to Follow”, Manila Bulletin, July 14 and 21, 2009; Lorna K. Tirol, “The Starmaker,” in Doña Sisang and Filipino movies, ed. Monina A. Mercado (Metro Manila: A.R. Mercado Management, 1977) 46; and Nestor U. Torre, “Doña Sisang: Her Times, Her Studio,” in Doña Sisang and Filipino Movies, 10-16. [↩]

- “Dapat pala, puro LVN na lang ang pinanood natin!” All translations from Tagalog to English are my own. [↩]

- Businessworld reports that, from 8,000 attendees at the first Cinemalaya in 2005, “the audience turnout for the film event has shot up by as much 54% every year. Last year, Cinemalaya’s box-office attendance ballooned to 42,000, from about 30,000 a year ago. For this year, Mr. Jardin said organizers hope to attract an audience of 50,000.” Jeffrey O. Valisno, “Old hands join newbies in Cinemalaya,” BusinessWorld July 8, 2010. Available http://www.bworldonline.com/weekender/content.php?id=13910. [↩]

- LVN is an acronym for the surnames of its three founders: Narcisa Buencamino vda de Leon, Carmen Villongco, and Eleuterio Navoa, Jr. Tiongson writes, “The 1950s and early 1960s have been described by many writers as the Golden Age of the Filipino film… [because] most of the films churned out by the Big Three Studios of this period – Sampaguita Pictures, LVN, and Premiere Productions… achieved a higher level of technological expertise and artistry in filmmaking.” Nicanor Tiongson, “The Filipino Film Industry,” East-West Film Journal 6.2 (1992): 29. [↩]

- Known simply as “Doña Sisang,” LVN Executive Producer Narcisa Buencamino viuda de Leon was the preeminent female auteur of the studio period. Film critic Nestor Torre credits Doña Sisang’s “painstaking attention to every phase of moviemaking” with creating the studio’s legendary house style. “Doña Sisang read scripts, decided on projects, supervised casting, designed costumes, viewed rushes, all down the line. This helps explain why LVN pictures tended to look and sound alike (“the LVN style”) despite the fact that they were filmed by many different megmen.” Torre, “Doña Sisang,” 14. [↩]

- “Bakit mo ipapakita sa tao na mahirap sila?” Quoted in Paulyn P. Sicam and Babsy Paredes, “The Director’s Director”, in Doña Sisang and Filipino Movies, 78. [↩]

- This film won Best Director and Actor at the 1956 Asian Film Festival FAMAS awards for Best Actor, Picture, Story, Editing, and Sound. [↩]

- Anne Friedberg, Window shopping: cinema and the postmodern (Berkeley and LA: University of California Press, 1993) 3. [↩]

- Almost 10 million Filipinos work abroad, accounting for nearly 10% of the total Phlippine population. For the Philippine economy’s reliance on ever-increasing remittances by Filipino migrant worker E. San Juan, Jr. “Overseas Filipino Workers: The Making of an Asian-Pacific Diaspora,” The Global South 3.2 (Fall 2009): 99-100. [↩]

- Susan Sontag’s appraisal of camp applies here: she calls it “a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation—not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy…People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as “camp”, they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.” Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp”, Against Interpretation (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1967) 291-292. [↩]

- For the disruptive figure of the vanishing lady in cinema, see Karen Beckman, Vanishing Women: Magic, Film and Feminism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003). [↩]

- “Ang gaganda nga pala ng mga tanawin!” [↩]

- I am thinking of the Freudian notion of the uncanny as the unfamiliar in the unfamiliar: “In general,” writes Freud, “we are reminded that the word heimlich is not unambiguous, but belongs to two sets of ideas which, without being contradictory, are yet very different: on the one hand it means what is familiar and agreeable, and on the other, what is concealed and kept out of sight.” Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny (1919),” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, General ed. James Strachey in collaboration with Anna Freud, vol. xvii (1917-1919) ‘An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works’. (London: Hogarth Press, 1955) 224-225. [↩]

- A The Balara Treatment Plant receives water sourced from the Angat Dam via the Novaliches Reservoir; it supplies the eastern half of Metro Manila. See “Metro Manila Water Supply System, http://www.mwssro.org.ph/publication_mm_watersupply_system.htm [↩]

- Vivian Sobchack, “Lounge Time: Postwar Crises and the Chronotope of Film Noir” Refiguring American Film Genres: History and Theory ed. Nick Browne (University of California Press, 1998) 130, 157-159. [↩]

I am looking for Pictures of the late Tulindoy..how come there are no write ups to this great comedian.

That’s not the Army Navy Club right next to the Manila Hotel. The Army Navy is across the park, you’re looking at a building across the pier.

Hi Jeric,

I was intrigued by your comment and my partner and I tried to do a little online research to figure out what that building really was. From what we can tell from aerial views of the Manila Hotel from Flickr (one black and white photo from the 1930s and an undated color illustration), you’re right – it’s not the Army and Navy Club but another building along Katigbak drive by the water, across the pier, as you point out. Would you know the name of the building on the left rear of the picture? The building appears in the b/w photo but not in the color illustration. Thanks for pointing this out! I’ll be sure to check the spot next time I’m in Manila.

Please see the Flickr images here, if you’re interested:

Unexpectedly, the “Kung Ako’y Mahal Mo” was an enjoyable and well-polished film by Dr. Gregorio Fernandez – the father of Merly Fernandez (of “Uhaw” fame) and the late Rudy Fernandez.

Nestor de Villa, known for his musical and comedy films, was able to pit it out with quadricentennial drama queen, Charito Solis.

Good to see the young and handsome Bernard Bonnin, real papa of BB Pilipinas Charlene Gonzalez, and lovely Lourdes Medel together as reel and real lovers in this film.

Yes, the urban sceneries of Metro Manila are well-depicted in this film like the case of “Victory Joe” on war-torn Manila and in other film retros.

Best of all the film is properly achived for future generations to enjoy and learn from!

Hi! I am writing a Thesis about LVN pictures! I hope you could suggest people mindful about this topic! articles,books,writeups especially people I can interview with. pls if there are anymore remnants of their headquarters I hope i could get a address so I could get a picture of it.

Pingback: Kung Ako’y Mahal Mo (If You Love Me, 1960) Balara scene | Face 3g