“They Have the Oscars”: Oppositional Telebranding and the Cult of the Horror Auteur

Joe Tompkins / University of Minnesota

“Heart-stopping violence. Explosive bloodshed. Undead flesh-eaters and dismembered ghouls. That’s right. I’m talking about all the shit we love in film, and all the finer things in this goddamn life. One man is responsible for all this. And that man is George A. Romero.” Such was the fulsome introduction Romero received at the hands of Quentin Tarantino at the 2009 Spike TV Scream Awards. The show, which claims to “celebrate the best in fantasy, sci-fi, comics and horror,” presents itself as a populist, if not entirely parodisitic, alternative to the more prestigious, mainline Academy Awards (the tagline reads: “Hollywood has the Oscars, but you have Scream”).1

Tarantino was there to present Romero with a substantial tribute: the honorary “Discretionary Mastermind Award,” which ostensibly celebrates those filmmakers whose “unique vision of horror, sci-fi, and/or fantasy is both critically acclaimed and culturally significant.” That Tarantino, perhaps the quintessential Hollywood auteur-celebrity, could be considered the right person for the job of bestowing Romero a quasi-lifetime achievement award for his seminal contribution to “all the shit we love in film” goes without saying. After all, Tarantino himself had been honored with the same award three years prior, alongside Robert Rodriguez, for their double-feature film Grindhouse (2007)—a big-budget homage to the kind of cheap, low-budget exploitation cinema that originally spawned films like Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). However, as was the case with Grindhouse, the purpose of the award presentation seemed to be less about paying homage to a “master” progenitor of low-budget “splatter” horror and more about drawing a direct lineage from one cinematically inglorious bastard to another. As Taratino would remark during his fawning tribute: “I’m here tonight to stand up for one of the coolest, the craziest, the scariest, and [one of] America’s greatest regional moviemakers of all time. I owe this man a huge debt, and so does every filmmaker who ever dared to declare their own independence, because George Romero did it first, and he did it with more guts and more gore than anybody.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h3q6OhYLrWI[/youtube]

Superlatives aside, we might take the occasion of this tawdry, televisual celebration of a cult movie “mastermind” to ask a more general, but pointed question: namely, what business does America’s “greatest regional moviemaker” have appearing on basic cable’s premier action network?2 Or better yet, what business does Spike TV—a channel that specializes in UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship) reruns and Ren and Stimpy cartoons—have in showcasing Romero, a notoriously political auteur who was once described by Robin Wood as “the most radical of all horror directors”?3 The answer, I would suggest, lies in part with the increasingly cozy institutional relation between Hollywood and its “ancillary” markets (most notably, television, video and DVD), and how these allow for industrial strategies (of branding, synergy, repurposing) designed to regulate and contain a proliferating field of consumer activities. In particular, “critical industrial practices”4 like the Scream Awards highlight just how much “ancillary” media stand to gain through an association with Hollywood’s more established forms of (cult) distinction.5 The “repurposing” of Romero’s cult auteur status by Spike TV is particularly salient in this regard for a number of reasons that warrant further elaboration.

First, is the way Romero’s contribution to early “independent” lowbrow filmmaking gets whittled down to its most gratuitous, sensational components in order to shore up the director’s reputation as a visionary herald of an “underground” cult aesthetic defined by excessive amounts of guts and gore. Contra the established academic interpretive/reading strategies, which typically approach Romero’s films in terms of their alleged radical political meanings, the “transgressive” aspects lauded here by Tarantino remain limited to those more or less outlandish stylistic features associated with cult film distinction.6 In this light, Romero’s “authenticity of expression”—his “unique vision”—can be summed up by his apparent go-it-alone willingness to directly confront the repressive strictures of mainstream, “good” taste. As the story goes, Romero’s defiance of stylistic convention, particularly his upping the ante of on-screen gore, effectively opened the door to subsequent generations of filmmakers (Tarantino included) eager to shock, offend and titillate through excessive displays of screen violence. Accordingly, what makes Romero “one of the coolest, the craziest, [and] scariest” of American filmmakers is not so much his artistic independence, nor his supposedly radical political agenda, but rather his role as an institutional fixture for a whole legion of fans, critics, and directors looking to cement their position within a (sub)cultural tradition of disreputable, seemingly uninhibited genre cinema.

Second, Tarantino’s hallowed affirmation of Romero as the director who “did it first”—despite remaining sufficiently vague as to what “it” actually is—rehearses an all too familiar canonical history of the horror genre, which cuts across taste cultures and interpretive communities. That is, whether one’s allegiance is to the deviant pleasures of cult movie fandom or the more bona fide intellectual pursuit of reading for “hidden” allegorical truths, Romero remains the go-to-guy; he is consistently situated at the fulcrum of American horror cinema’s iconoclastic rebirth during the late 1960s and 70s. And for this reason, his canonical auteur status remains largely unquestioned. Yet, the exact “cultural significance” of Romero’s auteurism is far from clear-cut. On the one hand, he remains an institutional fixture for “serious” film critics looking to champion a distinctive strain of politically subversive horror cinema—a camp we might identify with the more “legitimate” (read: academic) forms of criticism. This is largely due to the perceived social critique that is readily assumed to lie at the heart of Romero’s Dead/zombie films (e.g., lumbering zombies represent mindless consumers!). On the other hand, those same “oppositional” qualities are just as easily equated with cult film sensibilities. Indeed, it would appear that, for those Spike TV Scream fans who arrived at the award ceremony dressed as their favorite “dismembered ghoul,” Romero persists as the quintessential horror auteur, not because his films contain some radical political challenge to the social order, but because he seems to embody and openly embrace all of those features that correspond with a genuine cult cinema. In the words of Tarantino, not only did Romero do it first, he did it “with more guts and gore than anybody.” Again, Romero’s central contribution to the cult film community—his defiant confrontation with dominant conventions and Establishment culture—boils down to those “trash” elements routinely glossed over, or simply rejected, by the “official” film community, which are key to rendering the auteur-director a consummate symbol of “authentic” cult appreciation.7

Finally, it’s hard not to mistake in Tarantino’s prideful endorsement (“I’m here to stand up for one of the coolest, the craziest…”) a tiny hint of self-congratulation. And why not? The ceremony did, after all, provide the director—and self-proclaimed cult aficionado—further opportunity to heighten his own cult-auteur status by once more insinuating himself (if anachronistically) into exploitation film history. Never mind the fact that, as an industrial-economic category, regionally produced and exhibited exploitation movies of the Romero ilk effectively met their end in the early 80s, when low-budget genre cinema began increasingly to operate under the umbrella of a shrinking number multinational media conglomerates;8 the purpose of this trademarked tribute to a cult movie “mastermind” had more to do with convincing a “post-theatrical film culture”9 that a certain transgressive, underground exploitation community still exists—the growing obsolescence of repertory cinemas and drive-in movie theaters notwithstanding.

And here’s where the branded media showcasing of figures like Romero (and Tarantino) takes on new meaning. Particularly, as the “cultural geography” of cult movie fandom becomes more diffuse, or “less dependent on place,” cult movie audiences are transformed into a potentially more powerful market force.10 Indeed, the Scream Awards attests to this very fact: that is, that today’s cult film cognoscenti thrive not on the margins of media culture, but at its center, and that, what’s more, cult movie audiences have become increasingly integral to a host of ancillary media industries (TV, DVD, video games, commercial websites, blogs). Thus events like the Scream Awards prove indispensable for entertainment media moguls and cult film fans alike, as both appear eager to maintain sufficient levels of subcultural distinction amidst the ongoing “mainstreaming” of cult phenomena.11 Hence, the give and take: Spike TV attempts to trade on the nostalgic, “subaltern” sheen of an erstwhile “midnight movie” culture, while nouveau-exploitation Scream fans are provided the requisite air of (il)legitimacy with which to cloak their otherwise run of the mill niche cinematic pleasures. All the while, Tarantino keeps everyone assured that, indeed, “one man is responsible for all this…”

Of course, the adaptability of Romero’s particular brand of auteur celebrity fits comfortably here. For instance, I have already suggested that Romero’s reputation as a “rebel” auteur functions to guarantee a more “authentic” type of cult film encounter. However, it also appears that Romero’s transgressive iconicity serves equally well in a transindustrial capacity—that is, as a promotional category to be repurposed across industries, specifically for the purposes of organizing audience reception across multiple media/exhibition sites. For this reason, we might say that Romero persists as a commercially reputable “brand name vision”12 whose commodified public image remains viable principally for the ways it gets reworked and appropriated as both marketing category and interpretive position. Accordingly, his chief function as an auteur today has little to do with any actual textual output and more to do with the commercial conditioning of his cult status to fit a variety of institutional niches, discourses, and constituencies.

Joe Tompkins is a PhD candidate in the Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota.

Image Credits:

1. Scream Awards Logo

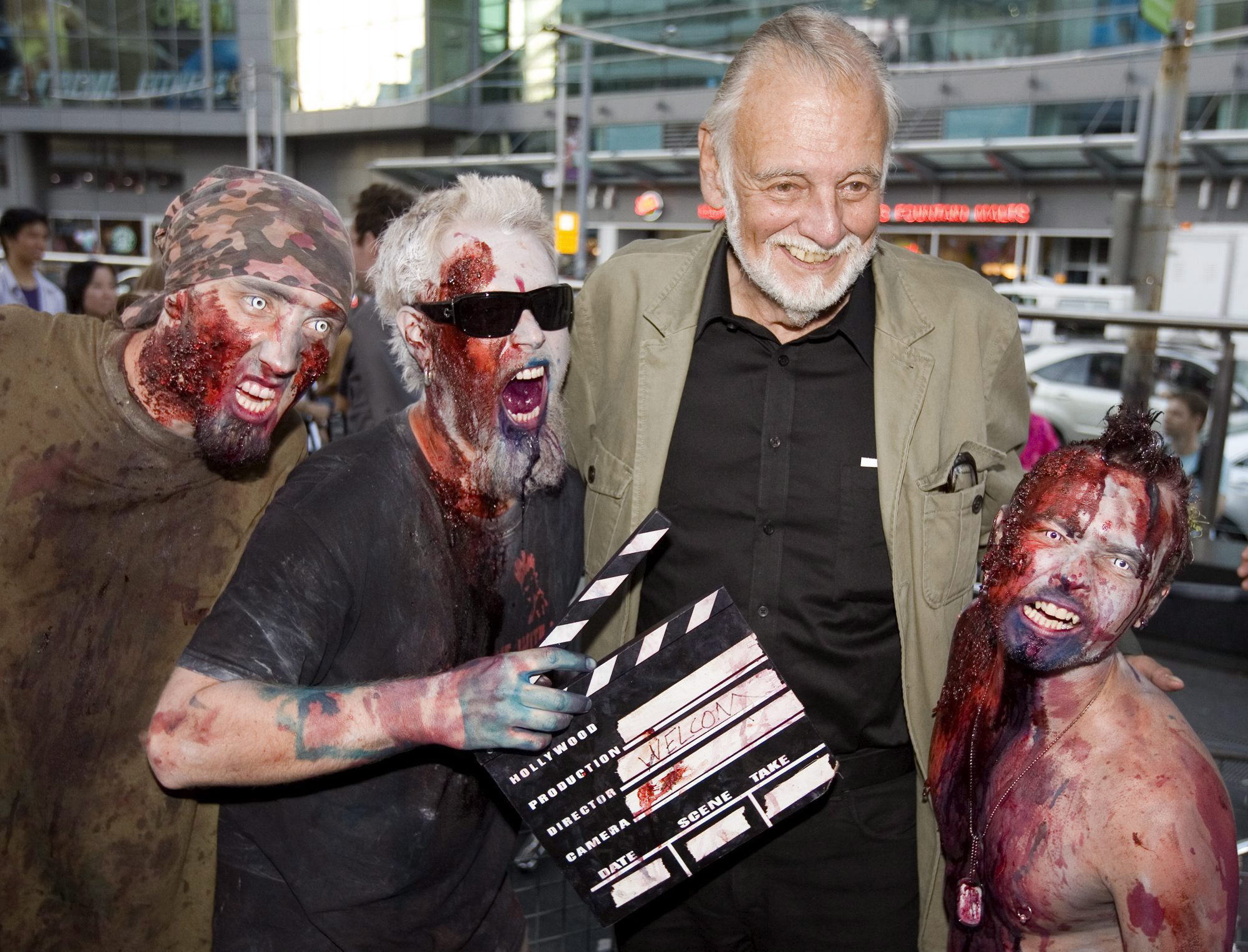

2. Romero with fans

Please feel free to comment.

- The show also maintains traditional award show categories, such as Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Director, while also putting its own decidedly irreverent spin on the genre by intermixing rather unorthodox categories like Best Villain, Most Memorable Mutilation, Holy S***! Scene of the Year, and the crème de la crème, The Ultimate Scream. [↩]

- Indeed, the Spike network (formerly The National Network, or TNN) has undergone a spate of brand makeovers in recent years. Most notable, perhaps, is the adoption of the “Get More Action” tagline in 2006, which functions as a double entendre, alluding at once to the network’s high concentration of syndicated action programming and the targeted audience of adult, heterosexual men presumed to enjoy such fare. [↩]

- Robin Wood, “Fresh Meat: Diary of the Dead may be the summation of George A. Romero’s zombie cycle (at least until the next installment),” Film Comment 44.1 (2008), p. 29. [↩]

- John Caldwell, “Critical Industrial Practice: Branding, Repurposing, and the Migratory Patterns of Industrial Texts,” Television and New Media 7.2 (2006), pp. 99-134. [↩]

- Recently, media scholars have begun to consider the impact of media convergence and new media technologies on cult movie fandom. See, for example, Timothy Corrigan, A Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture After Vietnam (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991), pp. 80-98; Matt Hills, Fan Cultures (New York: Routledge, 2002), pp. 172-182; Mark Jancovich, Antonio Reboll, Julian Stringer and Andy Willis, “Introduction” in Jancovich et al (eds), Defining Cult Movies: The Cultural Politics of Oppositional Taste (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2003), pp. 4-5; and Barbara Klinger, “Becoming Cult: The Big Lebowski, Replay Culture and Male Fans, Screen 51.1 (2010), pp. 1-20. [↩]

- See Jeffrey Sconce, “‘Trashing’ the Academy: Taste, Excess, and the Emerging Politics of Cinematic Style”, Screen 36.4 (1995), pp. 371-393; and Mark Jancovich, “Cult Fictions: Cult Movies, Subcultural Capital and the Production of Cultural Distinction”, Cultural Studies 16.2 (2002), pp. 306-322. [↩]

- Both Sconce (1995) and Jancovich (2002) have remarked upon the mutually “oppositional” character of both academic and subcultural audiences with respect to “mainstream, commercial cinema.” [↩]

- Kevin Heffernan, Ghouls, Gimmicks, and Gold: Horror Films and the American Movie Business, 1953-1968 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), pp. 225-226. [↩]

- Caetlin Benson-Allott, “Grindhouse: An Experiment in the Death of Cinema,” Film Quarterly 62.1 (2008), p. 20. [↩]

- As Jancovich et al (2003) argue, “New media such as video, cable, satellite and the internet have produced fundamental effects on cult movie fandom. On the one hand, these technologies have made cult movie fandom much less dependent on place, and have allowed the distribution and diffusion of cult materials across space. This has made possible the creation of large niche audiences that may be spatially diffuse but can constitute a powerful market force…new technologies not only allow fans across the world to communicate with one another and even organize themselves as a collective; it also enables industries to construct them as just another niche market” (4). [↩]

- Contra the suggestion of Jancovich et al (2003) that industry exploitation of cult movie fandom “threatens to blur the very distinctions that organize it,” I would argue that Spike TV’s brand exploitation works precisely because it upholds a necessary sense of “oppositionality” and exclusivity. Hence the tagline: “Hollywood has the Oscars…” [↩]

- A phrase borrowed from Corrigan (1991), p. 102. [↩]