Watching The Masters: Golf Becomes Exciting (In All the Wrong Ways)

Paul Achter / University of Richmond

As televised sports go, golf provides more than the usual number of challenges. For starters, golf is almost all downtime. During a typical tournament round, which lasts anywhere between four and six hours, players spend the majority of time doing three boring things: planning shots, walking to and from shots, and standing around while other players hit shots, and a typical tournament, they do this for four consecutive days. Visually, this just doesn’t work. The golfer’s swing and shot—the only real visually dynamic moments of action in golf—comprise just a small portion of a round. The rest is walking, waiting, and planning shots—nothing interesting enough for television. By cutting from player to player golf producers maximize the number of shots shown to give viewers a roughly synchronous experience of the tournament. Tournaments themselves occasionally do produce strong narratives: the best golf television happens when the tournament leaders make important shots at roughly the same time.

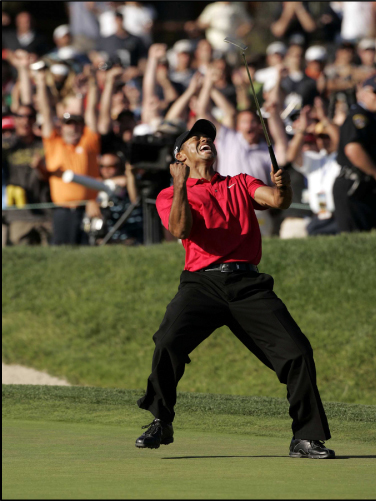

In addition to its technical anti-spectacle, golf tournaments are emotionally muted events, to say the least, and golf commentators are accordingly understated. When Tiger Woods sinks a long putt and pumps his fist, sending fans into a frenzy, it’s but a small episode in a dozen hours of weekend TV. In most cases, the professionals we see on television are a calm bunch. You can’t really blame them: unlike many other competitive activities, where athletes can gauge their opponents directly, golf isolates golfers from their opponents. Unless they regularly look at a scoreboard, which many are loathe to do, a tournament golfer cannot always be sure of his or her position in the tournament, leading them to adopt the philosophy that they are “playing against course” and not the other players.

Golf television1 compensates for its inherent lack of dynamic visual content and the emotional restraint of the players by attempting to endear audiences to the players, which is accomplished through the invention and circulation of narratives about the players and the tournament. In this respect, golf is like all major sports TV. Fans who know back-stories about a few of their favorite players experience their sport on television in a different way than non-fans do. For that matter, the way anyone makes sense of sports is dependent on their knowledge of the game and whether or not they have played it. NASCAR fans literally see a different race than I do; their “text” is denser than mine because the visuals work as cues to a series of scenarios requiring choices by the drivers and pit crews. For the serious sports fan, little may be required in terms of commentary and visually dynamic activity on the screen, because that fan comes already primed. If sports industries want build new fans, though, they must cultivate them, and they must reach beyond their events to attract and maintain them.

One of professional golf’s four major events, the Master’s Tournament at Augusta National Golf Club illustrates golf’s dependence on its players and their stories, and it also shows how the golf industry struggles over the way golf is portrayed. Often caricatured as a symbol of negative characteristics of “the South,” the Masters tournament draws the largest golf television audience of the year. For golf fans, it’s an exceedingly difficult ticket to find: the waiting list for passes to attend the event in Augusta, Georgia closed over thirty years ago. Most of us watch the Master’s on television, and we will forever.

However much the players, the club, sponsors, or other members of the golf industry would like to control the perceptions about Augusta National and its famous tournament, they have never been able to do so. The club goes to great lengths to monitor and manage the rhetoric of tournament coverage, including renegotiating its contract with CBS each year, which gives it a commanding position from which to change its representation. The club manages the language, commercial sponsorship, and the smallest details of production. During broadcasts, announcers must call those attending “patrons” and not “fans” or, as one unfortunate announcer put it, “a mob.” Augusta enforces these rules with an iron fist, forcing CBS to fire Gary McCord, a colorful on-the-course commentator, after he joked that a difficult area of the course was littered with “body bags” and quipped that the greens were so fast they must have been “bikini waxed.” It also limits commercialism: during weekend coverage, the club requires that CBS air only four minutes of ads per hour (the norm is 12) and it has on two occasions, in 2003 and 2004, run commercial-free on the weekend.

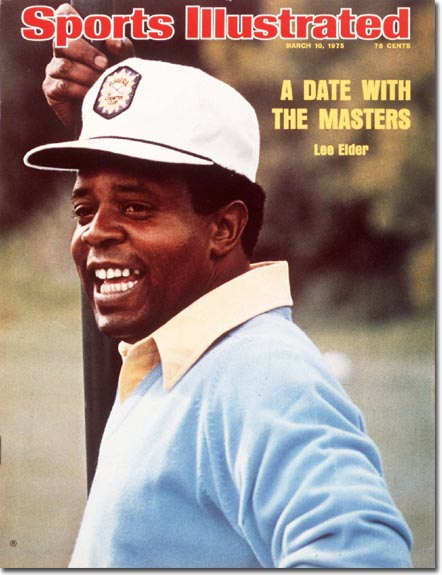

Though it enjoys an authoritative position in sports, Augusta has always had its critics, a condition generated by its popularity and visibility in the sports world and the largely negative perceptions of its elite, white, male membership. In 2002, feminist groups garnered a great deal of pre-tournament coverage with a well-executed protest of the club’s all-male membership policy. The campaign did not result in female members at August National, but it succeeded in embarrassing the club, it forced discussions of gender equality, and a few tournament sponsors and some members backed away. Moreover, it stole time from golf stories, such as the one about Tiger Woods, already a two-time champion. Woods is very important to the Masters and the Masters is very important to Woods. The tournament was one of the last to invite or qualify a black player, when Lee Elder qualified in 1975. According to David Owens’ The Making of the Masters, Elder’s qualification, because it came a year before the tournament, sparked a long and intense exploration of race, golf, and the south that required considerable effort by both and Elder club officials to manage. After Elder, and until the late 1990s, however, the only black people you would see at Augusta National, with few exceptions, were the ones carrying the clubs.

Just as Augusta celebrated Lee Elder and patted itself on the back for breaking a racial barrier in 1975, Tiger Woods’ arrival as a professional in 1996 was celebrated and promoted as sign that golf was no longer just the bastion of white male elites. In the early years, Woods delivered, giving golf a dynamic, winning player and a symbol of social change all in one package. This was good TV. Over time, people began to say that Tiger Woods transcended race, but what really happened is that his winning enabled the construction of a story and persona that was almost exclusively about golf. For the golf industry and the sports media, his steady accumulation of major tournament victories was the equivalent of the late 90s market bubble—he won so early and so often that all of the hype, product endorsements, and grandiose predictions surrounding him seemed justified. Despite the promotional army at his side, he mostly avoided questions about race relations and social change, almost guaranteeing that the story was always his golf. With each tournament win, with each step closer to owning all the major golf records, Team Tiger molded his image as an e-raced exemplar of hard work, discipline, and competitiveness. Given the force of his gifts and his remarkable ability to earn money for everyone, Tiger Woods more or less shaped his own image, and he really had no critics. It’s important to remember that with the exception of a small shoe line, Nike did not manufacture golf products until Tiger came along. They’re an entrenched player in the golf club, ball, and apparel markets today because of him. Woods had the upper hand and he controlled the narrative. The last time he missed a long stretch of tournaments, TV ratings dropped a whopping 47 percent.

Somewhere in a CBS Sports office in New York, a network official is laughing a wry laugh. Tiger returned to golf at this week’s Master’s Tournament, his first golf appearance since news of his adultery hit the web four months ago. Now the problem for golf TV is not so much that it is boring, the problem is that it’s exciting in all the wrong ways. How will CBS address Woods’ philandering and his stints in unspecified “rehabilitation” programs? Given Augusta National’s traditional insistence on tight lips, we can expect a great deal of discretion from Jim Nance and the other commentators. They will make allusions to Woods’ “off the course problems,” but little more. Talk about an elephant in the room.

In terms of which stories are told about Tiger Woods, everything starts over at the Masters. His career will now be framed as pre-and-post sex scandal. Giving short interviews without addressing questions about the scandal is unlikely to stop the questions and the search for stories about his affairs.

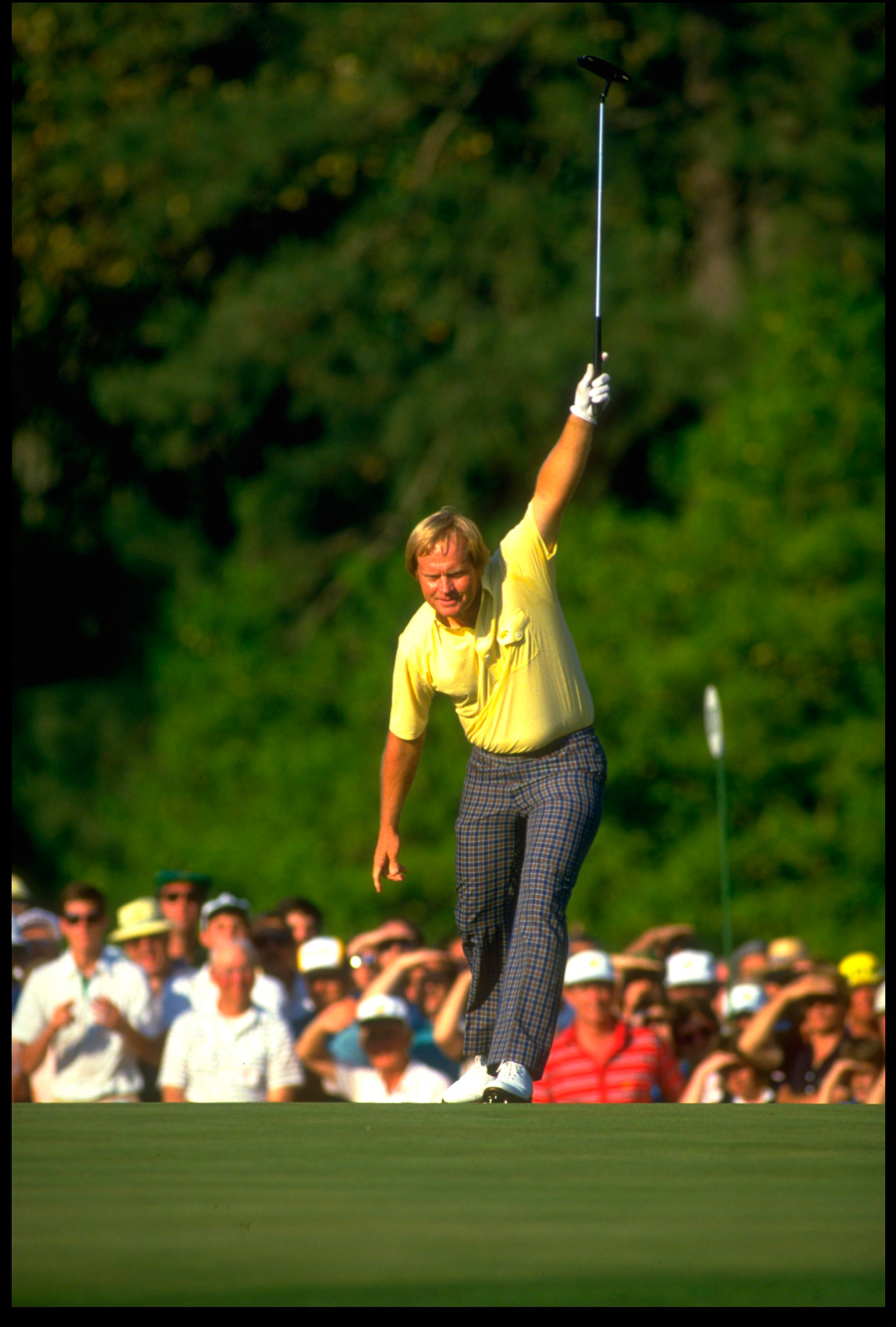

Team Tiger would like nothing more than if the story of Tiger Woods is always the one about a golf prodigy who chases and surpasses the record for major golf wins set by Jack Nicklaus. For now, at least, CBS Sports is likely to comply. But in the long term, outside of the small universe of professional golf, the only thing that will prevent scandal coverage is if Tiger wins golf tournaments. Nicklaus won 18 majors, and, so far, Woods has won 14. Before the scandal, Woods was on pace to pass Nicklaus and secure his place as golf’s greatest player. As he returns to golf this week the record takes on new meaning, because if he does not surpass Nicklaus, it will be attributed it to the scandal, and the legacy written will be one neither he nor his benefactors saw coming.

Paul Achter is an associate professor of rhetoric at the University of Richmond. He played on the golf team at Concordia College-Moorhead and earlier at Sauk Centre (MN) High School, where his team won back-to-back state championships.

Image Credits:

1. The challenge for golf is to make the game interesting to newcomers without losing what is distinct about it.

2. Tiger’s fist pumps are legendary, but they are relatively few.

3. Lee Elder’s qualification generated intense interest in the Masters and of racism in golf.

4. Jack Nicklaus winning at Augusta in 1986.

- I refer here to “stroke play” and not “match play” events. The match play style is a form of head-to-head golf, where players are placed in a bracket and play one-on-one matches until a winner is determined. Stroke-play golf is by far the most common format in the professional game. [↩]

I like your take here. I’m intrigued by how the commentators strive to weave together a coherent narrative of a golf tournament that relates the actual events of the play while taking into account different players with different backgrounds and individual stories. It amazes me just how much these commentators seek to impose a narrative on the overall tournament that speaks to just one player, or perhaps to just a few, and that therefore also inherently dismisses or even negates other competitors from the “story” of the tournament. Witness the Masters just completed, which ultimately became about Phil Mickelson’s win “for the family,” a rousing counterpoint to the blow to family implicit in the Tiger Woods narrative. It is the networks who create these narrative frames and who therefore control how we come to see the events when we view them through the medium of television, and I wonder at what cost? What is lost when we frame – or, perhaps better put, acquiesce to the framing of – these events?

Thanks for your comments Steve. I’m not sure exactly what is lost–it’s a great question–but I’m sure that folks who do reception studies would tell us that if we’re talking about what audiences loses, it varies depending on who’s doing the viewing, because the narrative frame can always be rejected. (Did you watch any free coverage online? I thought it was great). But to take your question more directly, the coverage this year submerged any real discord about Tiger, enabling the networks to produce something even more capable of generating capital. TIger’s Nike commercial was interesting in this regard, because it functioned as a form of apology for Tiger the person. Instead of Tiger selling Nike, Nike was selling Tiger, betting that people have to like him again before they’ll buy. There was a moment on Thursday or Friday when cameras caught an airplane banner mocking him, but that was about it. Of course, there’s a huge gossip industry happy to fill in where the golf media leave gaps, so “bad” Tiger generates capital, too. But the big sponsors and the golf industry need old Tiger, and they are off to a good start.

I agree with much of what you’re saying here. But I’d like to pose other questions which stem from your article. First and foremost, I want to entertain the idea of whether or not commentators/sponsors will move beyond the model of “integrating narrative” into golf programming. I for one, am tired of all the coverage of Tiger Woods’ personal life, and would like to see golf move toward simply giving us the play by play. I realize this is a bit of a conundrum, but I think it can be done. My primary example is baseball. Though baseball gets exciting, it doesn’t have the visual flair that a sport like basketball or boxing or football has. I would argue that it’s America’s pastime because of it’s relaxing nature, peppered with the excitement of a big moment. Golf operates in a similar fashion. Slow, slow, slow, BOOM. In all honesty, I do not see how “integrating narrative” became the norm for Golf programming, and I think it unnecessary. I’d rather just watch the golfers in all their intensity on the green, and imagine that I have a direct line into their minds: “how do I make the perfect putt?” That’s always been far more interesting to me then what color Gatorade Tiger is currently drinking with his kids.

On a pure “sports” note- Tiger is going to pass Jack. Even after this layoff, what is the result? He’s still a contender. Sure, there’s going to be rust, that’s expected, and his performance showed it. But more importantly, Tiger has TOO MUCH time on his side. I know I’m purely speculating, and you’re more qualified to speak on it (as you played collegiate/high school golf) but i just can’t see this personal business derailing him completely. Give him another year, and his game will be fine.

Finally, I just want to give you kudos for the breath of your article. You have golf history, race issues, commercial concerns, media, reception studies all in one article (I think I might be missing something too). Bravo.

Michael, thanks for your comment and the compliments. I agree with you that there’s more to be said in terms of commentary and the commentators. There’s been at least one good article about that on flow: http://flowtv.org/?p=859

Golf TV without commentators (or description only) might work for those with high knowledge of the game/sport/match. It would work for me–part of the reason I said so little about commentators here is that I don’t like to listen to Jim Nantz and Johnny Miller. They don’t do it for me. In other sports, like basketball, I really enjoy what they add, particularly people like Steve Kerr, Bill Raftery, Jay Bilas, and Jeff Van Gundy, who provide expertise about some of the more complicated strategies teams use during games. My preferences aside, I would argue that commentary and the narrative are crucial connecting fibers between the golf industry and new fans. Narrative is a common human form, and stories about infidelity and betrayal are especially capable of bringing in a wide audience because many people experience those things. I like what you say about fatigue–and indeed, I have been listening to sports journalists express it for weeks about Woods. If past sex scandals involving famous men are any indicator, interest in this will continue to ebb. Tiger can help the cause by winning and thus providing a story to compete with the sex scandal.

Overall, I really enjoyed this essay, and, like Michael’s comment above, I agree that you deftly cover a lot of issues in the Master’s alone that need to be addressed, including gender and race relations.

However, I disagree with your assertion that golf isolates golfers from their opponents; in fact, I think the dynamic of an indivudal golfer vs. his or her opponents adds to the narrative that the commentators and television producers try to convey. In addition to the golfers’ personal narratives, there are opponent-based narratives that mirror rivalries in team sports. Using your NASCAR example, NASCAR fans know of which drivers are teammates, and which are bitter rivals, and that makes their enjoyment that much better; it is the same in golf.

Television broadcasts do everything they can to structure tournaments to play up the narrative between opponents, moreso than they do individual narratives. In the first two days of a tournament, tournament organizers create pairings and threesomes of golfers that will be dynamic together, and often decide tee times based on the pairings that should get the most TV time: the players with the most interesting narratives and/or likely to generate the highest ratings (usually the pairing in which Tiger Woods is placed).

On the last two days of the tournament, players are paired based on their scores, with the leading pair last. In my opinion, you can’t get more compelling head-to-head opposition. Not only does the leading pair have the advantage of knowing how the rest of the field finished before they do (if they choose to look), but they also have the pressure of having to beat their playing partner. It’s not match play, but it’s close. In fact, often when Tiger Woods is in the final pairing, people tune in to see how well his opponent and playing partner can handle the pressure of playing with Woods head-to-head. Ratings for golf tournament Sundays where Tiger Woods is in the final pair far exceed ratings when he is not. Part of this is watching Woods himself; but people know he is good—what they watch for is whether the underdog can challenge him. Further, the narrative of inner tension between opponents dovetails with the public gentlemanly etiquette with which the players treat each other when playing. This is especially obvious with known foes, such as Mickleson and Woods.

In an individual sport like golf, or NASCAR, or tennis, half of the interest is in how the player strategizes against his opponent, and half of it is how he plays against himself. It is true that the golfers play against the course, but that is not solely what makes up the narrative that people tune in for; they want to watch the players interact, the dynamic between the opponents, especially the final pairing on the final day. The mental strain of having to stand up to someone like Tiger Woods and simultaneously play your best golf game is why people watch. In short, golf is twice as interesting because golfers really have two different opponents: the field, and themselves.

(And a truly minor quibble: you misspell Jim Nantz’s name in the article, but not in your comment above.)

Pingback: Albatrosses - Plasma Pool

Hilary, that’s some really good stuff. Thank you. The only qualification I would to your excellent point is that the narrative dynamic created by golfer versus opponent is not a very reliable one in stroke play events. As you say, the pairings make sure that head-to-head drama can occur, but quite often it does not. Tiger becomes even more important because he can still draw interest and ratings even in the absence of the drama provided by a close tournament. But when the tournament is a blowout and essentially decided with hours still left, or when a no-name wins, the narrative collapses. This happened in the 2009 British Open, albeit very close to the end of coverage. Tom Watson led for much of the tournament, and his win would have fit many feel good narratives–he was already a legend, he was a fan favorite, he would have been the oldest winner of a major–but he folded down the stretch and Stewart Cink won. Cink’s a talented player, by no means a no name in world golf circles, but still–the disappointment in the coverage and in the response afterward was palpable. Even Cink talked about how he would have liked to see Watson win.

As someone with negligible interest in both televised sports and Tiger Woods, I found your article very insightful, and it actually makes me want to go and watch some sports. Although I see why Tiger draws in audiences in this particular case, I hadn’t thought of the fact that sporting events continually draw audiences because of their moldable narrative qualities.

What similarities would you say exist between the way broadcasters shape news into narratives and the way sportscasters shape sporting events into narratives?

Hi Sonia K., excuse my delay while I’ve been wrapping up the semester. I’ve been thinking about your question and mostly, I’m stumped! It would be easier to tackle if one had an idea of the particular genre of news in question, because the narrative possibilities are dependent, in part, upon the “event” (crime differs from weather differs from sports). There are other factors at play, of course, such as whether the news event is live or based on footage. Sports are live events, generally, so perhaps you get less spontaneity and more formality from commentators in other news genres. But again, I’m just speculating because it is hard to generalize here.

Un très bon site riche en informations. j’ajoute votre blog à mes favoris. Bravo !

I really enjoyed this article and think it did a fine job of scratching the surface in the relationship between golf and television.

A few things I’d like to comment upon.

Because the inherent conflict of golf is man vs. nature or man vs. self, whereas most sports rely on man vs man, television programmers and commentators often relate golfer’s play on the course to their lives off the course. As a golfer looks over a 15 foot putt, knowing that a pregnant wife is waiting on the 18th green or that a sick father is resting in the hospital, this only takes the drama of golf to a new flight. It may seem exploitative but to keep golf popular, fans need the backstory.

My father was a professional golfer for over 20 years. When his first wife passed away, he was swarmed by media sources, all wanting to know how the tragedy would translate onto his golf game. Watching him finish 2nd on the first playoff hole in the 1990 Hardee’s Golf Classic (months after her death), provided a deeper emotional and compelling narrative for golf patrons.

Furthermore, I believe there is an interesting article to be written based solely on Tiger Woods and how he changed the way we’ve watched golf. Tiger has transformed the way athletes are shaped, the way they dress, and how they appear on television.

Thank you for the article and be sure to watch the new documentary The Short Game, which premiered at SxSW.