The Return of the Digital Native: Interfaces, access, and racial difference in District 9

Kevin Hamilton & Lisa Nakamura / University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

In her keynote address at the first Digital Media and Learning Conference sponsored by the MacArthur Foundation earlier this year at UC San Diego, eminent sociologist Sonia Livingstone asserted that “the hyperbole surrounding the notion of the ‘digital native’ (or ‘digital generation’) reveals a tendency to ask questions the wrong way round – as if the technology brought into being a whole new species, a youth transformed, qualitatively distinct from anything that has gone before, an alien form whose habits it is our task to understand.” 1 The notion that those born after 1980 are indeed “qualitatively different,” privileged objects of study whose alien nature requires new methods and paradigms of scholarship casts these individuals as ineluctably different from us older folk, who are disparagingly dubbed “digital immigrants.”

Yet digital technology, like all technology, is always already alien; despite its efforts to be or seem transparent, we all approach it with varying levels of access, ease and privilege, and as Livingstone’s empirical studies bear out, the imputation of “native” levels of expertise in regards to Internet use uniformly attributed to the young are not borne out in her observational studies. The digital native is a myth, one constructed by hopeful and/or ambitious parents, the press, and the digital/entertainment/industrial complex. The shrinking job market and tanking economy, in combination with the ongoing erosion of public education and the complete failure of the state’s obligation to teach technical competence create incredible anxiety. This combined with the extreme levels of competitiveness and technological knowledge required to compete in an increasingly informationalized world engenders fear for their (and our) future: it feels much better to assume that youth have these skills “naturally” or are born with them since they are unlikely to be given access to them in any other, more systematic, way. If they are not “natives” genetically or biologically endowed with privileged and even automatic access to the digital technologies, interfaces, and modalities of ICT’s, how else are they to come by them? If they are not born tinkerers and nerds, to use some of Mimi Ito’s taxonomies of youth and digital learning, who will invent the new stuff that will drive our economy forward?

There is however some political traction to be gained by paying some attention to this idea of the “digital native,” as phantasmatic as it has proven to be when applied to the real world. Indeed, this was an excellent year at the box office for representations of digital natives, as Avatar has proven, but it is Blomkamp’s popular and much better District 9 (which unlike Avatar failed to garner any Oscar love) and its depiction of other digital natives lets us question the unproblematic arc of adoption and value that pervades the digital native mythology. District 9‘s alien “prawns” are emiserated, “disorganized,” and “unhealthy” immigrants, users and creators of an advanced technology that they seem to have inherited, and that they only they can use, but in limited and apolitical ways that they themselves seem not to understand. In this way, they have a somewhat similar relationship to their own technology that the so-called “millenials” have to the Internet. More obviously, they exemplify Manuel Castell’s influential notion of the “Fourth World,” made up of “subpopulations socially excluded from global society”; they have a highly constrained access to ICT’s as users, and are thus permanently shut out of power as it circulates in the globalized world. However, in a relation reminiscent of both the case of Henrietta Lacks and the biopiracy industry, their genetic material is necessary to operate the extremely valuable “alien technology” such as the powerful weapons much desired by UMN–their bodies are the cheapest and most disposable part of the “soft” interface to extremely valuable hardware. The protagonist, Wikus, becomes an unwilling “digital native” when he undergoes a biological conversion from human to alien. His transformation from a citizen to a hardware peripheral, from subject to object, lets us weigh the trope of the digital native in the context of the Fourth World as well as our own.

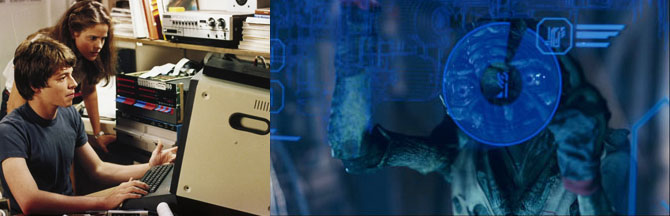

Consider the tinkerer in “his” cave – Bill Gates in his garage, Ted Kaczynski in his cabin, WarGames‘ David Lightman in his bedroom, or the alien Christopher in his shack. Despite their formal similarities, such characters are differently authorized to conduct their secret experiments. Wikus’ “find” of a shack full of old human tech would be a suitable setting for a young boy genius or a 1930’s radio operator, but for an unauthorized user such disorder and “late adoption” is a sure sign of deviance. Whether a hero of “global ghettotech” or a target for MNU detention, the alien tinkerer is alternately celebrated or suspect because she didn’t follow the arc of legitimate use from novice to expert. The alien user is doubly damned here; she is neither permitted to follow the arc, nor to break the story by achieving fluency through other means.

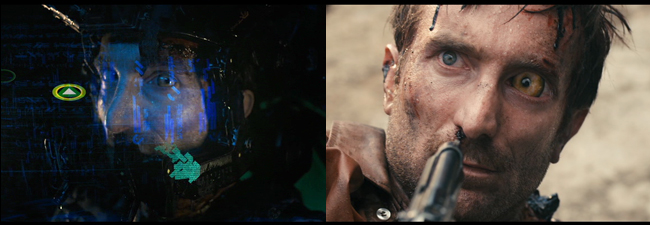

District 9 does contain a digital native who fits the common notion of the geeky little boy (never a little girl) who makes computers do amazing things (as in the film WarGames, a key text in the visual culture of digital tinkering and the trope of the digital native). Christopher’s son is able to pilot the mothership remotely using a sophisticated transparent heads up display that he plays like a virtuoso, demonstrating that it takes an alien, specifically a young alien, to engage with technologies proficiently. Of course the viewer roots for and is made to admire this reassuring display of competence, since it gives us a break from the unrelenting horror, fear, and anxiety that drives much of the plot thus far. It stands in direct contrast to Wikus’s abject abnegation to technology; the whiz-kid clicking and flicking his way through the haptic interface we are so used to from our ipods and pods fits nicely into the notion of the miraculous digital child, always-already able to perform the most difficult tasks with seemingly no effort, and with no help.

Among Wikus’ layered transformations, his body almost never leaves the moral control of his employer, the arms-manufacturer and military contractor MNU. At the film’s start, we see an unwitting Wikus in an unlikely promotion, serving as a surrogate in the delivery of MNU’s immoral relocation plan. He is good for them only as a body, one which conforms to the rules of procedure, management and policy. As an alien, he is just as transparent a conduit, a mechanism through which MNU enacts violence on others and displaces culpability. What changes here is Wikus’ awareness of his role in the transmission of death. His body also no longer requires the training of a career in management. As an alien, Wikus is far from fluent at firing weapons and killing – his torturers know more than he what uses his body might be good for in the enaction of violence and displacement of moral blame. They shock him into action, wrest him into unwilling fluency, and re-value him as a mere medium, rather than as an well-behaved agent. Wikus just moved down the ladder of global labor, across the sea to the roles that “other” peoples typically play. He has entered the Fourth World.

The hopes around computer interfaces have long positioned mastery and fluency as the only and static goal of all use. Epistemologists teach us that the virtuoso violinist’s relationship to her instrument is not always seamless, and even Heidegger’s hammer at times feels foreign in the hand of the carpenter. But the hopes around computers – if not always the actual design – almost universally situate fluent use as fluid use. In these visions, the user eventually achieves pure fusion with her console, and has arrived there only as a result of deft design and skillful operation. In this arc, the skin is the last bridge to cross in the divide between hand and instrument. The touch screen revels in this boundary, and the heads-up-display slices it even thinner, through producing a control surface with no thickness at all.

Though the heads-up-display plays a familiar role in District 9 for the proficient alien operators, only Wikus shows us the gooey gateway to the thinnest touch. His alien hand slips into a slimy hole, presumably facilitating a fusion of amino acids that obey no boundary, because they constitute these boundaries.

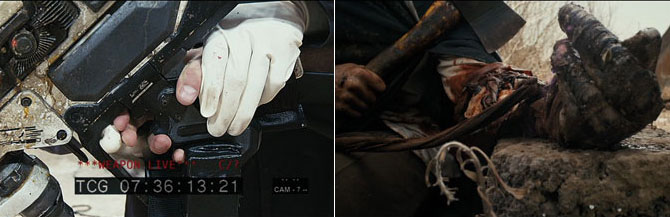

The hand is the key in District 9‘s story of bodies. In other narratives of unwilling racial or species transformation, the protagonist first notices (or doesn’t notice) a new feature in the mirror – the face is the place. Wikus’ exposure to the alien liquid was even through the face, yet the transformation begins in his hand. Where countless television and cinematic narratives rely on the DNA test to verify identity, the torturer-researchers of MNU take a much more literal approach; they force the body in question to fire a gun that only an alien could operate. Like the whiz-kid digital native who is assumed to be able to just “pick up” any device and use it perfectly and creatively, Wikus’s newly alien body is able to “pick up” any alien weapon or technology and deploy it without even meaning to–in a cruel scene of torture which drove at least one of our friends into the depth of her theater seat, Wikus is repeatedly zapped with a cattle prod and made to insert his alien hand into multiple weapons and demo them in front of an audience of scientists. This is a parody of the digital native mythology that reminds us: even if it is so that those born post 80’s can “pick up” any digital technology, under which compulsions do they do so? For whose benefit? What kinds of choices or agency are involved? For Wikus, at least in the first half of the movie, there are none. Wikus’ identity as an alien is confirmed through the violent use of his hands, and against his will. In fantasies of the “native user,” will usually plays little part in fluency; for the native, fluid use of interfaces should come as naturally as breathing. MNU’s confirmation of Wikus’ alien identity reflects a perverse exaggeration of this dream. Through forcing his hands around a deathly trigger, they remove will from the picture and compel him to perform their fantasy of effortless use. Terrified, Wikus looks to remove the offending limb – but this act of self-immolation is impossible, he cannot will his hands to do it.

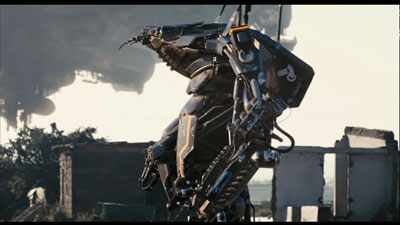

2009 was the year of the mecha suit, a much welcome feature of the science fiction film canon that was due for a revival. Nothing puts a smile on a sci fi fan’s face like a good mecha suit combat scene, and District 9 delivered, to great effect. These scenes exemplify Wikus’s corporeal distress as a technology user: rather than glorying, as we viewers do, in the prosthetic pleasures of catching RPG’s in flight, hurling pigs into buildings, and shooting absurdly overpowered weapons with unearthly accuracy, Wikus’s relation to the transparent interfaces of the alien body seems to be fraught with fear, confusion, pain, and anxiety. What’s more, it’s during these scenes of interpellation into the alien interface displays that we are shown that all interfaces are really alien, or rather, render us alien. Wikus’s left eye transforms into an alien eye, and we are reminded that his days of racial passing are over–he has permanently crossed a racial boundary.

The turning point of District 9 takes place during a beautiful conflation of willful moral action and un-willful inhabitation of identity. Wikus most resembles a “prawn” while in the mecha-suit. The animation of the suit, though modeled after motion-capture of the actual human actor, also shows Wikus at his most confidently insect-like. Walking away from the scene of violence, he pauses to listen and look at the mother ship moving away. From inside the suit, Wikus is in bewildered and traumatic rapture, but from outside he looks wholly embodied and of one piece – he truly appears as alien. (Later, we will barely glimpse his movement as a fully-transformed prawn, but as the technologically-augmented shape of a prawn, Wikus moves with grace.) It’s at that very peak of bug-ness that he makes the most willful decision of the film, a moral choice to turn and save the alien Christopher, no matter what the benefit or harm.

There has been much debate about the meaning of the technical competence displayed by Christopher and Son; their digital nativity seems to call the idea of the “stupid prawn” into question, and seems to present a problem at least with continuity if a series flaw in narrative logic. Instead, their story represents the political coming to consciousness of the “digital native” and the extremely partial and unevenly distributed reclaiming of a technological birthright. If aliens in other films always know how to use technology perfectly, these aliens do not. The lie of the digital native is revealed when we witness Christopher and friends painfully reconstructing their hardware from garbage gleaned from a city dump–surely a visual reminder of the highly toxic and miserable electronic metals reclamation industry in China. Technical mastery is more hard won for all of us than we would like (or perhaps can afford to) to admit, but as this scene points out, it is harder for some than others. The global South is present and alive in District 9 in a way that is entirely unavailable in Avatar, another film about technologies, natives, and difference. While Jake Sully’s crossing over from one race to another, from human to alien, is all about transcendence (as Neo murmurs in the first Matrix sequel when he encounters bigger, stronger, faster enemies: “upgrades”), in District 9 it is all about abjection, technology as an agent of compulsion and oppression as well as possible empowerment, racial ostracism, and thwarted longing. In short, District 9‘s lack of 3D bells and whistles doesn’t make it less “real” than Avatar; though it’s a world that none of us long to enter and inhabit, we don’t need to, for we are already there.

Image Credits:

Authors’ screenshots

- http://www.scribd.com/doc/27906764/Sonia-Livingstone-2010-Digital-Media-and-Learning-Conference-Keynote [↩]

An intriguing part of this article for me is the statement of “digital technology, like all technology, is always already alien” which I think is eloquently fleshed out by the mention of Heidegger’s hammer and the virtuoso violinist’s relationship to her instrument; this sort of tension of technology always threatening to slip out of control. And certainly this subject has gotten proper attention from popular media throughout most of the modern age from films like the Terminator, to the hype surrounding the Large Hadron Collider. Though to what extent do we take the discussion from technology, as such, to the arena of technological and scientific progress. While discussions about technology seemingly push us into thinking about the future, so much of the discourse is rooted in the past, particularly this article makes me begin to think about the manners in which technology and notions of progress served the aims and was the impetus for colonialism, and how much our notions of modernity and technological progress owe themselves to these histories of inequality and economic exploitation. And surely contemporary discussions over issues such as globalism and labor policies in the developing world are inseparable to this. And even in a film such as District 9, which isn’t necessarily about this, in its subtext “it is all about abjection, technology as an agent of compulsion and oppression as well as possible empowerment, racial ostracism, and thwarted longing.”

Pingback: Internet Art – The Art of O :: Uncategorized :: Exeter area parents learn to be Internet savvy