Flow Favorites: Digg, Flickr, and the Colonizing of Bridging Texts

Vanessa Au / University of Washington

Every few years, Flow’s editors select our favorite columns of the last few volumes. We’ve added special introductions and asked the authors to revisit their columns and add a comment afterward. We’ve also appended the original comments to the post. Enjoy!

Co-Coordinating Editor Alexander Cho:

Pieces like this are what Flow is all about. It’s a forum for testing out new ways of thinking about interesting issues in our complicated media landscape, like an academic stretching their muscles. In our semi-formal arena, Au is able to blend her own poignant experience with a political analysis that calls attention to the fact that social media is intimately threaded through with unspoken race and gender codes — unspoken, that is, until someone chooses to nominate themselves. What happens next — when so-called “bridging texts” are themselves colonized — is often overlooked in much scholarship on the supposedly liberatory potential of new media.

The army green t-shirt that catapulted me to internet fame for a day references a scene from Stanley Kubrick’s 1987 film Full Metal Jacket in which a Vietnamese prostitute says to an American GI, “Hey baby, you got girlfriend Vietnam? Me so horny. Me love you long time.”

The line “me so horny” has since been reproduced in countless pop culture texts, including rap group 2 Live Crew’s song “Me So Horny,” which reached number one on the U.S Billboard Hot Rap Singles in 1989.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m0YJCAedY0w[/youtube]

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DbaFM_CA4mw[/youtube]

Earlier constructions of Asian women as prostitutes actually predate Kubrick’s film by nearly a century. According to Robert G. Lee, more than ten thousand Chinese women were forcibly brought to the United States as prostitutes in the late 19th century, thereby reinforcing Edward Said’s claim that the West had Orientalized the East by exotifying Asian women (88).1 Since then, many popular culture texts and western practices have reproduced this narrow construction of Asian women as sexual playthings.

My shirt, which reads “I will not love you long time,” is a statement of resistance to the construction of Asian and Asian American women as objects of white male sexual fantasy both in Full Metal Jacket, as well as in the broader American imaginary. Through the act of wearing the shirt, the “I” on the shirt refers to me and the statement becomes my own. As Vincent Pham and Kent Ono explain, wearing or producing activist counter-shirts that requires linking knowledge of Asian American history to humiliating stereotyped constructions of Asian Americans is itself a rhetorical act that allows us to be seen, not as passive model minorities, but rather as activists and political participants (193).2 Indeed, disrupting this narrative of the apolitical model minority while contesting the construction of Asian women as prostitutes and sexual playthings was my intent.

Tasha Oren explains that recent public expressions of grievance like mine from the Asian American community have mostly been over our cultural significations, “media representations and the pernicious repetition of stereotypes” (338) such as those perpetuated by numerous offensive representations of Asian Americans in the media and illustrated on apparel.3

Corporations, she explains, “miscalculate the ‘sensitivities’ of Asian Americans” because there is a lack of association between us and racial anger in the cultural imagination, which facilitates our positioning as a demographic “free of past grievance–in short as honorary whites” (353). In other words, Asian Americans might not be the target of racial insensitivities as often as we are if, perhaps, there were more visible public expressions of Asian American anger about our stereotyped and humiliating representations.

Oren explains that there are, however, several examples of counter-narratives that make these expressions public. Oren reads the Secret Asian Man comic strip by Tak Toyoshima as one such example of a widely-distributed mainstream cultural production that gives a voice to the grievances of Asian American activists. She also names the web sites Angry Asian Man and Big Bad Chinese Mama as texts that use anger and media criticism to voice racial grievance. She calls these “bridging texts” because they bring Asian American grievance into the realm of mainstream popular culture thereby disrupting the trope of Asian repression. Oren explains that they are effective because these “mainstream expressions of racial grievance, of anger, of a refusal to ‘suck it up’ are at once metaphoric and actual interceptions. In their textual presence and performance they can short-circuit old ‘oops’ formulas by insisting on the specificity of [Asian American] experience” (356).

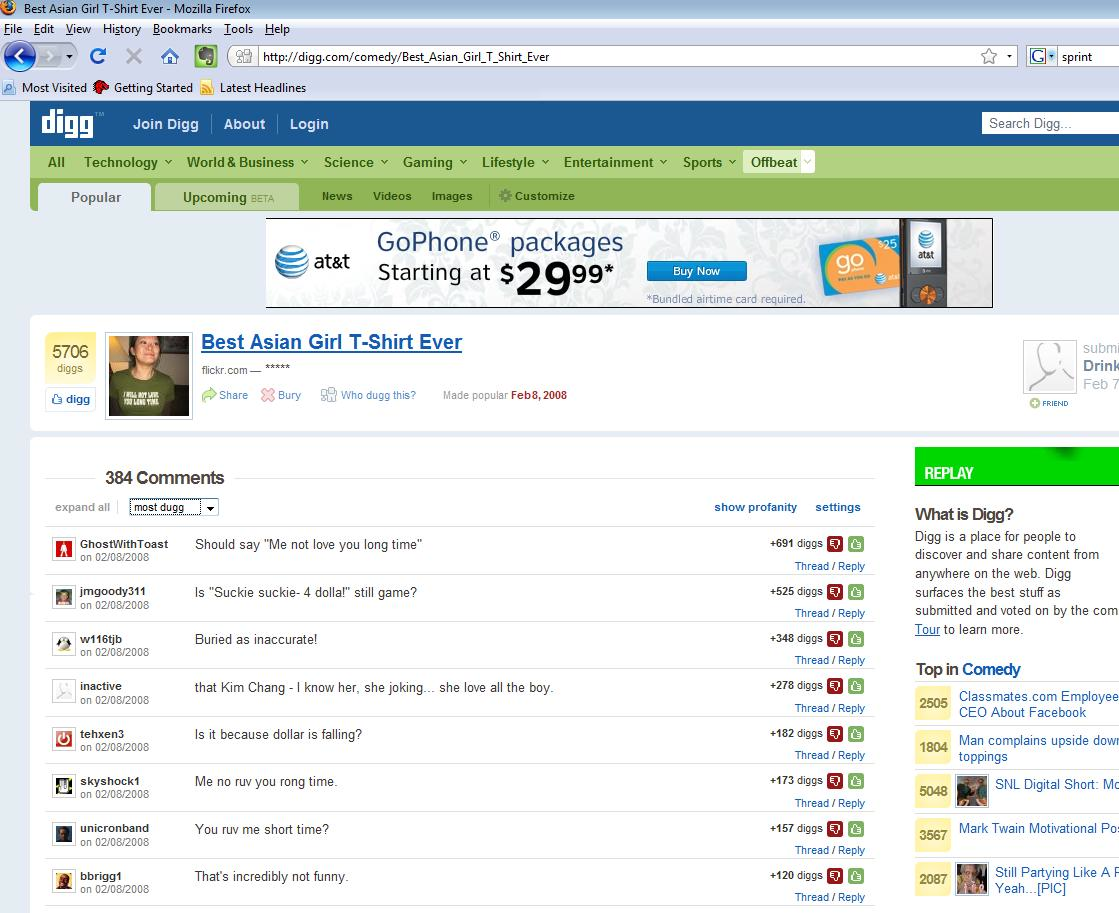

But the question remains, how do we figure whether Secret Asian Man and other bridging texts actually succeed in contesting dominant constructions of Asian Americans? My statement of resistance to the construction of Asian women as prostitutes became an interesting case for re-examining Oren’s argument about the resistive meaning-making that happens by way of bridging texts. When a very popular user on Flickr, an acquaintance of mine, posted the photo of me wearing my “I will not love you long time” shirt and the page hosting the photo made it to #1 on Digg with 5706 “diggs,” it reached a large mainstream audience and in that moment the photograph became a bridging text by Oren’s definition. The difference between this text and those cited by Oren, however, is that social media sites like Digg and Flickr invite public dialogue which effectively becomes incorporated as part of the text, while such opportunities for participation are absent from sites such as Angry Asian Man, Secret Asian Man and Big Bad Chinese Mama.

When audiences can contribute to the generation of a bridging text, such as on the Flickr and Digg pages that hosted my photo, they can shift the meaning of the text. I argue that social media web sites like these can in fact reignite expressions of traditional or “old fashioned” racism, which Chesler, Peet, and Sevig define as the “expression of traditional negative prejudice, bigotry, stereotypic beliefs about the inferiority or even dangerousness of people of color” (219), particularly when readers can post their contributions to the dialogue anonymously.4 Although theorists including Eduardo Bonilla-Silva argue that a more socially-acceptable “color-blind racism” (2) has replaced old fashioned racism, old fashioned racist sentiments seem to flourish when identities are hidden or falsified online.5

At least half of the comments on either social networking site could not be read, even generously, as a support for, or even recognition of my act of grievance. Instead, many of the comments are anonymous personal attacks condemning my opposition to the construction of Asian women as prostitutes and sexual playthings. Often they are neither subtle, nor color-blind. For example:

Sie Sind Schwach says: So, you won’t “Love me long time”, you’re scrawny, and quite angry. What use are you then? Are you good at math or something? It doesn’t seem like you have a developed sense of humor. I thought plain looking girls were supposed to try harder.

lossjim says: [to the owner of the Flickr page] you have one friend with SERIOUS issues, and, to boot, comes off like most “holier than thou” asian chicks, with a low self esteem, but need to be seen/appreciated? whatever, good luck with your “good friend”

Other comments reinscribe the very construction I was attempting to contest, the Asian woman as prostitute/object of white male sexual fantasy, or perpetuate other humiliating constructions of Asian Americans such as the non-English speaking foreigner. For example:

jonolan says: No boom-boom, no visa!

promqu33n says: needs more chinglish. me no love you longtime.

slider527 says: ahahaha me want fly lice with that asian girl.

A critical analysis of all the comments and the meanings they produce is beyond the scope of this short monograph (but forthcoming in a separate paper). What I am suggesting here though is that the narratives created in these spaces–one that condemns my act of grievance and another that reproduces and reinscribes common stereotyped constructions of Asian Americans–overshadow and displace expressions of Asian American grievance both literally and discursively. Oren points out the importance of bridging texts in interrupting narratives of Asian American passivity that can lead to miscalculations of our tolerance for racially offensive cultural significations, but the construction of a whole new text–pages upon pages of online reader-generated comments–clearly take up more space in a literal sense than the original bridging text. Space allotted to the act of grievance is effectively colonized by commenters, many of whom react with hostility. The examples of online expressions of Asian grievance that Oren cites do not provide a space for public dialogue as do social media sites such as Flickr and Digg. Thus, we need urgently to complicate our understanding of how bridging texts operate, or fail to operate when the texts themselves enable audiences to effectively re-author the content. What happened on Flickr and Digg around my voicing of racial grievance suggests that while any disruption in the persistent narrative of passive model minority is important, it is crucial to consider how the text might produce different meanings when it is visually and discursively colonized by oppositional discourse.

Vanessa Au is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Communication at the University of Washington. Her current research explores online public discourse around Asian American contestations of Orientalism in contemporary American popular culture. A software product marketing manager in a previous life, she is currently working on a manuscript for an edited volume on transgressions and web 2.0. Vanessa is a member of University of Washington’s Asian American Studies Research Collective and Women of Color Collective.

Vanessa Au revisits her column for Flow Favorites:

Looking back at my May 2009 FLOW article, Digg, Flickr, and the Colonizing of Bridging Texts, made me think more about anonymity on the web and whether the colonizing of “bridging texts” with blatantly racist and sexist commentary reveals a racism that still exists today despite popular claims that, since the election of President Obama, we live in a “post-race” society where racism ceases to affect the lives of people of color. Writing this article piqued my interest in a broader question that extends beyond the specificities of understanding how bridging texts can fail in a social media environment. Rather, why in the first place are people so eager to express such blatantly racist and hostile views and with such vehemence? What might this vitriolic racial backlash reveal about expectations of colorblindness and political correctness that have figured so prominently in American society since the 1990s? And, finally, how might we still use social media effectively in anti-racist efforts knowing the dynamics produced by anonymity and structures that enable users to colonize web space? These are the urgent issues facing race and new media scholarship, and shaping my own research trajectories.

Image Credits:

1. “I will not love you long time” t-shirt, author’s screenshot

2. Abercrombie and Fitch t-shirt

3. Adidas shoes

4. Digg page for “I will not love you long time” t-shirt, author’s screenshot

Original Comments:

Alex Cho said:

What an interesting experience, Vanessa. Thanks for writing about it. One thing I am curious about, since I don’t use digg – do people “digg” things they don’t like? For example, you mention you got 5,076 diggs (wow!); to “digg” something means to “dig” it, yes? I’m not 100% sure. But either way, I wonder if there are a lot of people who support your political statement implicitly by the act of “digging” – and thereby broadcasting to their own networks – but decide not to participate in active commenting. I hope so, at least.

This also reminds me of the mixed backlash when Chris Crocker, already a YouTube “celebrity” who challenged mainstream gender conventions, became world news with his “Leave Britney Alone” video. People in the comments section of his YouTube video page reinscribed all sorts of homophobic and patriarchal ideologies on his ambiguously-gendered performance. What could have been a “bridging text” seemed downgraded to a sounding board for reiterating conventional stereotypes. Or, given these two examples, is that reiteration an inherent property of a “bridging text”?

-June 1st, 2009 at 10:39 amVanessa Au said:

Hey there Alex, that is actually part of one of my arguments in the longer version of this paper which I’m working on for an edited book! Stay tuned and cross your fingers that the publishers take it! Thanks for commenting!!

-August 28th, 2009 at 9:05 pmPaul said:

Nice page and a good expose of the foul stereotypes that Asian women have had to endure (your T is the perfect rIposte BTW!). The products from A&F and Adidas are incredibly insensitive and remind me of the images of African-Americans in US advertising half and century ago. I wonder, Vanessa, if you have read the book “Asian Mystique” by Sheridan Prasso? It’s on my ‘to read’ list and currently sitting on my bookshelf and I’d like to know you views on it if you’ve read it. Thanks also for the tips about where to dine in Vancouver on your website. I’m going there with my wife and baby daughter this Christmas and will check out some of the restaurants you mentioned. Regards, Paul in Calgary.

PS. I wouldn’t over analyse the purile comments left on your friends flickr page (some of which you’ve featured above). They are from idiots who are doubly racist and sexist and to comment further would give them more credence than they deserve.

-December 5th, 2009 at 10:41 pmVanessa Au said:

Hi Paul,

Thanks for your feedback! I hope you had a fantastic time in Vancouver.

I hadn’t heard of Asian Mystique. Great recommendation, just requested it from my library.

re: your PS. Great point about giving them more “credence than they deserve” though it is interesting to think about what provokes such responses and what they might suggest about our racial climate and what people long to say but only when they are anonymous.

-February 24th, 2010 at 3:32 pm

Please feel free to comment.

- Chesler, Mark A., Melissa Peet, and Todd Sevig. “Blinded by Whiteness: The Development of White College Students’ Racial Awareness.” White Out : The Continuing Significance of Racism. Eds. Ashley W. Doane and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. New York: Routledge, 2003. 215-30. [↩]

- Pham, Vincent, and Kent Ono. “”Artful Bigotry & Kitsch”: A Study of Stereotype, Mimicry, and Satire in Asian American T-Shirt Rhetoric.” Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric. Eds. LuMing Mao and Morris Young. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 2008. [↩]

- Oren, Tasha G. “Secret Asian Man: Angry Asians and the Politics of Cultural Visibility.” East Main Street: Asian American Popular Culture. Eds. Shilpa Dave, LeiLani Nishime and Tasha G. Oren. New York: New York University Press, 2005. [↩]

- Chesler, Mark A., Melissa Peet, and Todd Sevig. “Blinded by Whiteness: The Development of White College Students’ Racial Awareness.” White Out : The Continuing Significance of Racism. Eds. Ashley W. Doane and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. New York: Routledge, 2003. 215-30. [↩]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists : Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006. [↩]

Hi Vanessa,

I wanted to let you know that I thoroughly enjoyed your article. I am currently in a class titled “TV Culture & Society” and we recently talked about the portrayal of Asian people on television for a portion of our class. Our professor showed us clips from old television shows and films, similar to Full Metal Jacket. She described to us the objectification of Asian women by American men, but did not talk about how Asian people are choosing to fight back today. I think it’s great that Asian people are becoming activists, and standing up for their race. I agree that big networks believe that there is a lack of anger in the “cultural imagination” like you described. I really enjoyed the examples of the comic strip and your photo being posted on Flickr. I think it was an interesting point to make about how sites like Flickr sometimes cause negativity and racism to start up again because people can say thins anonymously. Thank you!