“I See You?”: Gender and Disability in Avatar

Michael Peterson, Laurie Beth Clark, and Lisa Nakamura

When we committed to write about Avatar several months ago, we had no idea that it would be the most profitable movie ever.1. The stratospheric costs of the film’s production set a very high bar for profitability. This film, which ultra-auteur James Cameron imagined 1975 but could not make until CG technology evolved to create this particular artificial world, both profits from and critiques technology. And in order to do this, it focuses on bodies–non-normative, genomically identifiable, gendered bodies. Annalee Newitz points out in “When Will White People Stop Making Movies Like Avatar” that the film’s plot revisits and revises of the narrative of going native, leading many, including television’s South Park, to deride it as “Dancing with Smurfs.”

Clearly, Avatar lends itself to a critique of empire, yet has not yet been read in terms of its most striking visual trope, exploited in the trailer: disability. It is precisely because gender and disability are persistently addressed in the film but not in commentary about the film that we know how central it is. As Cameron said in his interview with Newsweek this January, “It’s the Story, Stupid,” his attempts to “sell” the movie were far more successful when the trailers depicted Jake Sully’s disabled body than when they focused on depicting the lush landscape and ultra-expensive “effects”. Cameron claims that the second trailer emphasized “story” or narrative, a feature that even the most effects-driven films must have (and a feature that keeps them well within the genre of narrative film rather than spectacle, as most IMAX films have been) and that the film’s success is ultimately due to this.

Though technology can fix many things in Pandora and in our world, it still apparently cannot or rather chooses not to fix human bodies. This is of great note in a film that both displays and is about the transcendent qualities of CGI and biotechnology. When Jack Sully transmits his consciousness into the hybrid Na’avi body that he eventually comes to occupy permanently, a world of limits is evoked. We can see that the bias against disabled people is exactly the same in the future as it is at present–one passing soldier refers to Sully as “meals on wheels” and another replies “that’s just wrong,” apparently refering to Sully’s very presence on Pandora.2 Sully’s spinal injury is repairable, but he can’t afford it. However, as we see during the avatar-training scenes, the disabled body is viewed as “waste” that a thrifty military industrial complex can recoup. Disposable military bodies, often bodies of color in this film, are continually sacrificed: Sully is given the ability to acquire a prosthetic alien-soldier body not as compensation for his disability, but in spite of it–his genomic capital as the identical twin to his scientist-brother makes him the only possible match for the cloned Na’avi body, a technology far more expensive and precious than his own defective body.

The film’s tag line “I see you” points both to the film’s innovative technological apparatus, the glasses and screen and images that let us see like never before, and to the possibility of empathy…towards aliens. What does it mean that, while it’s possible in Avatar to see a critique of both gender and disability, this is not what critics seem to be “seeing”? The disabled body in this spectacular film is the sole spectacle we are meant to look away from, the blind spot in this visual field which otherwise seems to invite immersion.

While Jake’s masculinity is called into question via these disability hazing rituals, Avatar is constructed specifically for a heterosexual male fantasy of penetration–the question is whether the film’s revisions to this structure are decorative or substantial. The movie first hyper-masculinizes Jake, who bursts into his re-born ability in a boyish romp across the avatar base, but then pursues dual tracks of developing his violence-capable masculinity and at the same time steadily feminizing him. He learns not to stab Gaia with an improvised flaming spear, but instead to engage nature through a collaborative hairstyling.

This interbraiding is probably not an intentional homage to the performance artists Marina Abromovic and Ulay, who in Relation in Time (1977) sat for 17 hours with their hair braided together, though this lengthy film does give extended consideration both to asymmetrical warfare (involving both male and female warriors) and to an exploration of spiritual connection with the world which is figured as material–that is, as scientifically observable.

One obvious visual pleasure offered up by Avatar is the spectacle of the giant, blue-skinned nearly nude Neytiri; in an interview with Playboy Cameron acknowledged (or bragged) about the centrality of her “smoking hot” body to the picture: “Right from the beginning I said, ‘She’s got to have tits,’ even though that makes no sense because her race, the Na’vi, aren’t placental mammals.” However, Cameron’s feminist sensibility must be acknowledged, and the violent maternal figures played by Linda Hamilton in Terminator 2 (1991) and originally by Weaver in Aliens (1986) are central to the pleasure of those narratives. Cameron’s feminism, however, appears both narrow and generalized to the point of meaninglessness in Avatar.

Action films now seem either conscientious or trendy about including women capable of violence, as evidenced by the Lord of the Rings films’ efforts to beef up the roles of Liv Tyler and Miranda Otto. Here, while Weaver appears in a kind of homage to both her earlier role with Cameron and to her characterization of Diane Fossey in Gorillas in the Mist, Michelle Rodriguez essentially reprises her role from Aliens as a butch marine with a penchant for salty tag-line dialogue (and has her own moment of going native when she wears a discreet swoosh of war paint as she pilots her helicopter into battle against the human mercenaries). The film is full of gestures of equality and showcases female combat and leadership, yet those touches should not obscure how deeply the narrative is organized by gender. For example, the male Na’avi understand weapons, and the women understand the network.

The planet’s network-culture decides what peripherals or hardware can interface with each other; one could say that it organizes both ability and gender. It regulates what organ can plug into what port or orifice; echoing the technological machine culture of the military industrial complex, the planet’s animals are the peripherals or hardware that the natives employ as prostheses. The culture of positivist digital technology development, exemplified by Avatar‘s telegenic, Minority Report-style interactive displays and 3-d imaging, echoed in the film’s exhibition itself, is contrasted with the earthy pleasures to be had from the groovy eco-spirtuality of the “Gaia Hypothosis,” in which the natural world is considered as a single living organism.

Near the end of the film, after the big battle has, in effect, been won, Colonel Miles Quaritch, wearing a mecha-suit, a metal prosthetic soldier body (very similar to the suit Sigourney Weaver wears at the end of the Aliens) goes to find Jake Sully for a form of personal revenge. This battle is fought between a stereotypically virile hyper-masculine marine who controls his mechanical body physically, and a biological being, “wet ware,” controlled by a disabled, feminized body so vulnerable that it cannot reach its own breathing machine. Ultimately, Neytiri joins the fight, bringing a third term to this hard body / soft body dichotomy. She is a real being. Her body is visually but not ontologically like Jake Sully’s avatar body. The thanator, a violent and uncontrollable animal that submits to her for the purpose of this fight, signifies the seamless and intuitive connection with “nature” that crunchy feminism has often attributed to women. Neytiri and her mount disrupt the oedipal conflict between two men and their prostheses.

Neytiri is then seen cradling Jake’s tiny, frail human body. While this scene replays–with genders reversed–the scene in which a giant avatar version of Jake Sully cradles a tiny dying human version of Grace Augustine, it also has some significant ramifications for our concerns with gender and disability. The scene is an odd pieta, but rather than the Virgin Mary cradling the dying Christ, we see powerful, authentic female nature nurturing the damaged vestige of masculine humanity. Here Cameron may for the first time in the film go beyond his earlier butch feminist heroines to offer a queerer formation of gender and ability.

It’s easy to bash Avatar. In fact, the proliferation of reviews in the popular press that do a good approximation of an academic critique of colonialism leads us to wonder how this critique came to be part of popular culture. So common is the “Dances with Smurfs” critique that when someone forcefully and coherently takes a contrary view it’s worth paying attention–as with the argument made by Metafilter user Pastabagel, who asserts that “the plot is completely predictable, not because you’ve seen it before, because you actually haven’t. Avatar differs from the plot of every single one of those archetypical films in one extremely important way – the forces of civilization/progress/technology lose.” Whether this defeat is either unique or transformative might be debated, but this argument usefully demonstrates our faith in science fiction’s ability to get us beyond the trap of our own historical postcolonial moment. It seems, however, that our current ideologies of gender and disability are harder for the film to transcend.

In the final scene of the film, then, we find Scully laid at the foot of Tree of Souls in order to transfer his “soul” from his human body to his avatar/golem. If Avatar suffers from the same traps of all the nativist fantasies that have preceded it, both filmic and literary, in this fantasy the protaganist must literally die (just as humanity has been literally defeated). In order to occupy a place in the world of the Na’avi “others”, Jake Sully must fully relinquish this human form. There will be no going back. While this could be seen as another Christian reference (this time to the Resurrection), it is also a fantasy of being able to live in virtuality, leaving our physical bodies, and their political baggage, behind.

As media critics, we have a responsibility not just to bash Avatar, but to come to terms with its remarkable popularity, which has occurred either because or in spite of the ease with which the film can be critiqued for its virtual colonialism. Avatar is popular because it provides a good deal of spectatorial pleasure to a relatively diverse audience, pleasure that for some has turned into depression as they realize that Pandora is an artificial world, and not one they can enter at will. It’s no wonder that some audiences are said to experience such powerful post-Avatar blues, a nostalgia for an entirely artificial place. The film gives us a navigable-looking virtual world (modeled after the groovy visual style of Roger Dean, a favorite of the stoner set from the 70s) and it’s not surprising that audiences are disappointed that they can’t live there (without dying first). And its narratives about transcending or “losing” the defective bodies resonates particularly strongly in the age of reality programming such as The World’s Biggest Loser and Extreme Makeover.

Avatar manages to bring together spectators that like war movies with spectators that like peace movies. It’s of equal interest to adults and to children. It offers points of identification for folks who are diversely positioned by race and by gender. Can we derive any reasonably hopeful message from this popularity? Is there any chance that these differently positioned audiences are talking to each other about the issues raised in the film? Or are we simply seeing the movie side by side, taking away our separate messages, and going home changed only by the weight we gained from our buttered popcorn and twizzlers? The centrality of disabillity and gender in the film’s narrative is easily hidden within its lush CGI-generated landscape–a visual achievement which is its most powerful agent and advertisement–yet which grounds it back in the body, just where the viewer finds herself when she takes off her 3-D glasses.

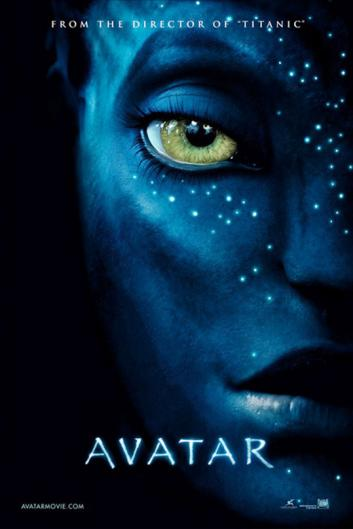

Image Credits:

1. Avatar movie poster

2. Jake Sully, the wheel-chair using hero of Avatar

3. Na’avi and Jake

4. Thanator attacks Sully

Very interesting article folks. I appreciate your attention to gender and disability in this film, which have – as you point out – been overlooked in favour of more obvious critiques of its colonial discourse.

While it is true that Michelle Rodriguez gives her usual one-note performance as a bad-ass Latina (a la Girlfight, Fast & Furious and Lost), she was nevertheless not the bad-ass Latina in Aliens that you refer to. She would only have been about 8 years old. The butch marine you seem to be thinking of is Private Vasquez who was played by Jenette Goldstein, another one of Cameron’s favourties who turns up again in Terminator 2 and Titanic.

A very interesting article! I agree with a lot of your points, especially regarding the “blind spot” of disability in criticism of the film. Moreover, I’m intrigued by your use of “golem” in the third-to-last paragraph, as golems are protectors and ciphers for communities. Though Rabbi Loew created and controlled the Golem of Prague, but it was created to serve the Jewish community, and in some versions I heard grew in relation to the fear that community felt. So to introduce the term golem into Avatar seems both strange and fitting and worthy of some more unpacking.

Very interesting piece! One comment from the Dis Studies perspective: great to have a dis/abled character, shame he wasn’t played by a dis/abled actor. The stereotype noble savage of the Nav’i extended here, as no Nav’i that we see has any form of visible dis/ability. Another thought might be that the 3-D versions require such an enhanced version of spectatorial immobility à la Mulvey as to constitute a form of cinephiliac impairment, the absolute necessity of not moving, of keeping the eyes slightly out of focus, in the mode of the old stereoscopes.

I did like the ‘blue face’ comment in regard to Avatar as the Jazz Singer 2!

Pingback: Men and Their Prostheses - Plasma Pool

Pingback: KJELL STJERNHOLM Teater & Funktionshinder: Avatar

Pingback: Lost and masculine mobility | Dis/Embody

I must admit that I was largely oblivious to the problematic representations of both gender and disability in Avatar (2009) before reading this article. Much like the first paragraph suggested, most criticisms I have encountered regarding the film were either tied to race in some way or decried it’s similarities to Dances with Wolves (1990). Neocolonial and neoliberal critiques have also been common. And yet this is the first time I have seen or heard issues of gender or physical disability enter the conversation. Why is that, I wonder? Let’s say for a moment that we were meant to overlook Jake Sully’s paralysis. Why have the problematic representations of gender and heteronormative sexuality not received more attention? This is a sincere question for which I do not have a decent answer. Particularly because feminist thought has been around for so many years, I find it especially odd that such criticisms seem to remain uncommon.

The “looking away” from Jake Sully’s physical disability seems slightly more complex to me. I wonder if, in some way, his disability is what makes us accept his transformation. If he were not in some way “otherized” in his human life, would he really be able to fully identify with the Na’avi when placed in opposition to the human invaders? So then we do see it…kind of. But how this half-recognition impacts our experience is only marginally outlined here and a more detailed exploration of the issue is surely needed.

Finally, I would also like to look more closely at this association of Sully’s physical disability with femininity. I wonder if this is not slightly problematic. On one hand, I see the argument, yet on the other, I feel it is counterproductive to one of the larger points of the article. It seems that one of the central arguments here is that Avatar promotes negative or stereotypical views of gender. Yet the argument that Sully’s physical disability feminizes him is only logical if these negative and stereotypical views of gender are accepted (i.e. weakness=feminine). I am not sure how to resolve this contradiction without restructuring this portion on the argument; however, I would like to see the issue explored a bit further.

Pingback: Critique of gender and disability in Avatar « Unstable Bodies

Pingback: Syllabus « Pop Culture E2043

Pingback: Lisa Paitz Spindler, Danger Gal»Blog Archive » Danger Gal Friday: Neytiri

Pingback: Avatar: Empire’s Analogical Machines - Plasma Pool

Pingback: Avatar I See You | More More Pics

This article inspired me to think about the representation of disability in the movie. Disabled people are still portrayed as pathetic and ridiculed. The real hero is Jake’s avatar, not the disabled himself. This further highlights the disadvantaged image of the disabled group.