Women in Post-Democratic Italy: A documentary perspective

Michela Ardizzoni / University of Colorado at Boulder

2009 seems to mark a turning point in the history of Italian documentary filmmaking. In the past year alone, two young documentarians have embraced their cameras and their dissatisfaction with Italian media to produce two visually strongly and discursively sharp films. While their respective foci are somewhat different, both directors aim at exposing the superficial commodification of celebrity status and women’s bodies that has characterized Italian television in the past 30 years and has been nurtured by the growth of Prime Minister Berlusconi’s media empire.

Erik Gandini’s “Videocracy” suggests that present-day Italy is no longer a political democracy, but rather a tv-based democracy: what matters in the Italian socio-political milieu is what airs on television; therefore, if people and issues are not popularized through the small screen, they consequently do not warrant any serious attention. In this sense, television in Italy has come to dictate the agenda for the public sphere. The problem in this line of thinking arises when such agenda includes, almost exclusively, fame, beauty, physical prowess, amorality, and disrespect for gender equality as pivotal features to succeed in 21st-century Italian society. Through an extensive review of many hours of current and old footage, Gandini, an Italian-born, Sweden-based filmmaker, succeeds in eliciting the intricate connections between the ‘culture of appearances’ (cultura dell’apparire) and the oligopolistic nature of Berlusconi’s regime that have bestowed upon the ‘image’ the power of democracy. As Gandini puts it, “In a videocracy the key of power is the image. In Italy only one man has dominated the images for three decades. He was a TV magnate, then President: Silvio Berlusconi has created a perfect combination, characterized by political and entertainment television, as anyone else influencing the content of commercial television in the country. His TV channels, known for the excessive display of seminude girls, are considered by many a mirror of his tastes and his personality.” The seemingly illogical link between futile television stardom and real political power has proven strong and durable not just for Berlusconi himself. Indeed, his present cabinet features a 36-year-old former showgirl, Mara Carfagna, as (the ironic) Minister for Equal Opportunities , the evident corroboration of the extent to which mediatic power yields a place in the national public space of politics.1

One of the sustaining arguments of “Videocracy” is the confining notion of ‘reality’ that is engaged on Italian television. Here, reality is visibly gendered, sexed, classed, and politicized, and leaves no room for alternative or apparently unorthodox views. The democratic political system in Italy is thus bound to collide with the highly oligopolized nature of the media and the conformist social perceptions they foster. It comes thus as no surprise that the “Videocracy” trailer, used to promote its screening at the 2009 Venice Film Festival, was banned from public television in Italy on the grounds that it represented a personal attack against Prime Minister Berlusconi. In their rejection letter, RAI claimed that the spot is offensive to Berlusconi and indirectly addresses the recent sex scandals in which the Prime Minister was involved by underscoring the link between Berlusconi’s network and the proliferation of images of scantily clad young women on television. This recent incident clearly elicits the role of public television as subservient to the political establishment and ultimately incapable of fulfilling its public service goal.

The inevitable intricacies between media and politics in Italy tend to focus often on the centrality of the body as the new cultural capital in this late-modern society. Whether it’s the heteronormative, overly virile male body or its exoticized and objectified female counterpart, public discourse, regularly informed by the media, lingers on the idea of the body as the preeminent form of identification and individual expression. This obsession with physicality is at the center of Lorella Zanardo’s short documentary “Il corpo delle donne” (‘Women’s Bodies’), released in the Spring 2009. Zanardo, a management consultant on diversity and equal opportunities, wrote and directed this documentary as an attempt to expose the ubiquitous and almost pornographic display of women’s bodies on public and private television channels alike. The 25-minute-long video successfully merges the most popular images of female bodies and the pervasive insistence on lips, breasts, bottoms, and hips shared by day-time and nightly programs. As an almost desperate cry for help, “Il corpo delle donne” provides visual evidence of the way in which Italian women have been trained to use their bodies as marketing tools to penetrate the flimsy world of television stardom and social power. Women, Zanardo argues, have thus acquiesced to seeing themselves exclusively through the patriarchal, masculine lens that frames them day after day. In this context, it is their vulnerability, their frailty, and their ultimate submission to male desires that constitute the most appealing traits of televised women.

Yet, as Gandini’s work on Italian videocracy reminds us, these traits are hardly confined to the small screen. Rather, the circus-like hyperreality of television has become the normalized standard for large sections of Italian society, culture, and politics. In the 2008 Global Gender Gap report, which looks at economic participation, educational attainment, political empowerment and health, Italy ranked 67th out of a total of 130 countries – lagging behind almost all other EU members and several developing countries, such as Mozambique, Tanzania, and Ukraine. If this report is indeed indicative of the status of women in Italy, one can easily draw a direct connection between the humiliating representation of women on television and their second-class status in what _i_ek calls a ‘post-democratic’ state.

In conclusion, 2009 might prove to be a decisive moment in the history of Italian documentaries, a history abounding with short documentary films (11-13 minutes on average) but lacking in longer, more developed works. This paucity has characterized especially the past four decades, when the production of medium and long documentaries has been erratic and inconsistent. As noted by Aprà in his survey of the Italian documentary, post-world-war-two productions have focused mostly on travel, eroticism, and montage, while investigative works are scarce and often unknown.2

The crisis of democracy at the heart of Italian media and Italian society alike might actually stimulate the resurgence of a dormant documentary tradition, which, aided by globalization and new technologies, could reclaim the publicness of a space and a culture that have for too long been privatized and stifled.

Image Credits:

1. Silvio Berlusconi

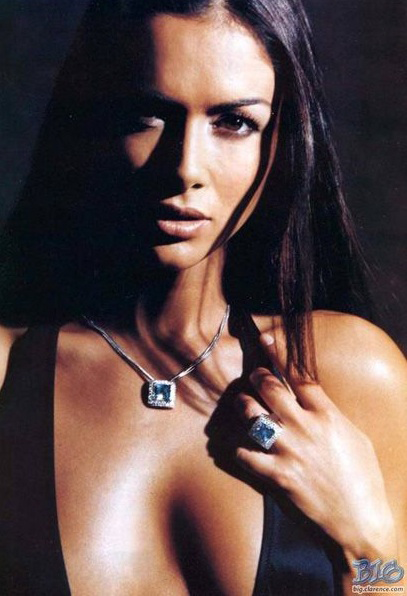

2. Mara Carfagna

3. Silvio Berlusconi

- After a decade-long career as a nude cover girl on several men’s magazines and as a showgirl on Berlusconi’s network, Carfagna was in charge of the women’s section of Berlusconi’s rightist party Forza Italia. Not surprisingly, Carfagna was at the center of one of Berlusconi’s controversies, when, commenting on her beauty, he stated “If I were not married already, I would certainly marry her [Carfagna].” [↩]

- Adriano Aprà “Primi approcci al documentario italiano”, adapted from “A proposito del film documentario,” Annali dell’Archivio audiovisivo del movimento operaio e democratico, 1, Roma, 1998, pp. 40-67. This survey does not include documentaries made for television. [↩]