Foam Finger Cubicle: Selling ESPN360 as Workspace Media

Ethan Tussey / UCSB

Before he passed away in late June of 2009, Billy Mays had established himself as cultural icon of the infomercial genre. His energetic manner and booming voice provided just the right amount of exaggerated sincerity that has proven irresistible to the YouTube remix community. Mays’ resonance with “technologically savvy multi-taskers” was undoubtedly the reason that ESPN selected him to be their official spokesperson for their online sports video service ESPN360.1 In a series of advertisements that began airing in December 2008, Mays self-consciously employs his brand of histrionics to argue that advances in streaming internet video technology have created a “revolutionary” moment for sports fans. The rhetorical appeal of these advertisements is designed to expand the venues of the sports media from the living room and the stadium to the cubicle, and in the process, transform the meaning of sports fan activities.

Internet video services like ESPN360 attempt to transition the communal activity of fandom into a rebellious act against the monotony and oversight of the stereotypical work place. The discourse of the advertisements and the design of the video player situate sports viewing as a type of “workspace media.” Workspace media is a term I have developed to describe internet media content that is designed to be consumed and shared in relation to the rhythms of the work environment. The term emerges from a path of scholarship that considers the impact of digital technology on the traditional viewing contexts and meanings of entertainment content. Barbara Klinger’s 2006 book, Beyond the Multiplex: Cinema, New Technologies and the Home includes a chapter on e-films and web parody that posits the idea that internet content is often treated as an, “antidote to office or school routine, while fitting seamlessly into both the surfing mentality that defines media experience and the multitasking sensibility that pervades computer culture” (200). Though Klinger is describing web shorts, her characterization of the viewing mentality of the workspace is instructive to an analysis of the discourse of internet video services like ESPN360.

The advertisements for ESPN360 characterize the work environment as a dehumanizing and lonely wasteland similar to the depictions of films like Mike Judge’s Office Space. In the commercial entitled Billy Mays Office a cubicle worker claims that watching sports at work is “better than doing work at work” while another states that ESPN360 makes the workday “way less soul crushing.”2 Another commercial, called Billy Mays College, features a student closing his books and opening his laptop with the explanation “I’m not that strong a reader.”3 Though these testimonials are heavily coated in sarcasm the message is clear, ESPN360 is a new media technology that allows for multitasking and a sports fan experience in traditionally professional contexts.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PWPwrIVk6v4&feature=player_embedded[/youtube]

ESPN’s identification of the office as a viable market for sports viewing is not a new concept. Since 2006 CBS Sportsline has offered a streaming video service for the annual NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament. The tournament’s opening rounds air every year in March with many games beginning during the day. Employee organized “office pools” have been a popular way to create interoffice contests and community since the 1980s. Live video streaming of the event has only increased interest and media coverage of office viewing. Each year articles are written that decry the billions of dollars that have been lost because of the widespread watching of the NCAA tournament in offices across the country.4 In these articles a dichotomy is created between the efficiency standards of work and the cathartic, community building effects of sports video in the office. Clearly, the sports video providers are building on this dichotomy in their advertisements and in the design of their video players.

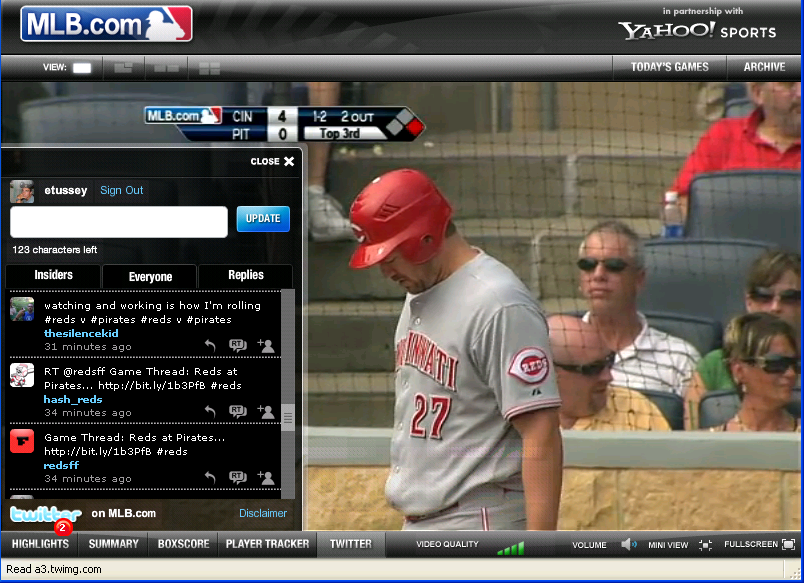

Sports video players, like Adobe Flash’s MLB.TV, attempt to channel office sports fandom into interactive features. Buttons on these video players allow the workspace sports fan to chat or Twitter with other sports fans that are logged in and viewing. This allows the workspace audience to check in with the game’s events and the viewing community while shifting back and forth with work projects. While writing this article I logged on to the Twitter feed connected to a recent Reds v. Pirates day game and declared that I was watching while working. Within minutes I received a response exclaiming, “watching and working is how I’m rolling,” and another offering to help me write this article. Most of the other comments had to do with brief observations on the game. The activity on the chat window demonstrates the mode of viewing for MLB.TV day games. The game discussion and brief interpersonal conversations provide a way to communally update the audience on game events, making it easier to follow the progress of the game (without sound) while maintaining a productive work flow.

The perception that the workspace media venue is a distracted viewing experience is a key tension of the transition to online sports viewing. In our current economic moment the threat of layoffs makes workspace media a particularly risky activity. One manifestation of this tension is a feature installed into the CBS Sports viewer called the “boss button” which when clicked transforms the video player into a spreadsheet full of numbers and nonsense data. During last year’s NCAA tournament when 92% of the online video audience for CBS was watching games from work computers, the “boss button” was pressed 2.5 million times.5 Close inspection of this spreadsheet disguise reveals it for what it is, a humorous but ineffective attempt at avoiding surveillance. Yet this button is much more significant as a symbol of the meaning of online sports viewing at the workspace.

Fans have often been described by media scholars as the most advanced examples of the active viewing audience. They are distinguished from other types of viewers because of the way in which they appropriate entertainment texts for their own communal meanings and uses in daily life. The rise of digital technology has increased the evidence of fan activity. Scholars and industry professionals that subscribe to the tenets of Convergence Culture argue that digital technology requires a more collaborative and responsive relationship between producers and consumers. Often this has translated into entertainment industries efforts to facilitate fan activities through proprietary channels of industry owned new media products. P. David Marshall argues that the entertainment industry’s ability to switch their mode of address from a traditional stationary audience to a “user-subjectivity” has resulted in the “most successful new media entities.”6 He points out that “In the various online services that have emerged in the latest generation of the Internet, what is highlighted is the ease of use for personal expression, exhibition, and distribution.” Reflecting on the discourse and design of the online sports video players, it is apparent that a particular user-subjectivity is being constructed around workspace media. It is one in which the media industries and the fan audience conspire together to “borrow” time from employers in the name of fandom. The inclusion of the “boss button” and chat features materially deliver on the promise of the advertisements, that online sports viewing is a way to bring leisure activities to the “oppressive” site of labor.

While these employee tactics seem to be an affective way of “sticking it to the man,” we must not forget the economic imperative of the media industries when considering the creation of a workspace media sports fandom. Though the discourse and design of online video players cast entities like ESPN, CBS and MLB as members of a fan community these companies obviously have a disproportionate amount of power. Scholars like Mark Andrejevic have argued that new media interactivity is merely an industry tactic for mining audience data and creating more insidious strategies of capitalism.7 John T. Caldwell has similarly warned that “second shift” new media products serve as a way of establishing conglomerate synergy within the open space of the World Wide Web.8 These two scholars raise important questions about the economic motivation for industry collaboration with fan communities. It must not be forgotten that the media industries and employers are both driven by a commercial economic system. Thus online sports video services must be understood within a framework of what Manuel Castells calls “informationalism.” As digital technologies and networks facilitate the blending of the lines between work and leisure we must remember that the destruction of barriers affects both sides of the divide. To accept the discourse of workspace media, being offered by ESPN360, is to participate in an economic system increasingly defined by instability, fluidity and the value of networking.

Ethan is a PhD candidate in the Film and Media Studies Department at UCSB. His scholarship primarily focuses on Hollywood’s relationship to the digitally empowered public. He is particularly interested in the ways that niche communities interact, interpret and re-imagine mass media texts. His forthcoming dissertation entitled, “Workspace Media: New Media Technology and the Monetizing Efforts of the Entertainment Industry,” examines the production, distribution and reception practices related to online entertainment content.

Image Credits:

1. Billy Mays at the office – author’s screen shot

2. March Madness on Demand – author’s screen shot

3. Watching and working – author’s screen shot

Please feel free to comment.

- Sultan, F. and Rohm, A. (2005) The coming era of “brand in the hand” marketing. MIT Sloan Management Review 47, 83-90. [↩]

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PWPwrIVk6v4, accessed September 24, 2009. [↩]

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0MQzgd_cfw&feature=related, accessed September 24, 2009. [↩]

- Goldinger, Dave. “Workers Find Bettor way to Spend Madness Time,” Daily News. March 18, 2008. [↩]

- Petrecca, Laura. “It’s tempting to watch NCAA games at work, but keep it under control,” USA Today. Money; pg 3B. March 19, 2009. [↩]

- Marshall, P. David. “New Media as Tranformed Media Industry,” in Media Industries: History, Theory and Method ed. Jennifer Holt and Alisa Perren. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2009. p85. [↩]

- Andrejevic, Mark. iSpy: Surveillance and Power in the Interactive Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007. [↩]

- Everett, Anna and John T. Caldwell ed. New Media: Theories and Practices of Digitextuality. New York and London: Routledge Press. 2003. [↩]

I’m really interested in this idea of a ‘media second-shift’ — as a graduate student, blogger, Flow Editor, instructor, and celebrity gossip aficionado, I often feel that I should be multi-tasking while ‘at work.’ I should keep my celebrity twitter feed, blog reader, and my own blog stats up and running — just like a ‘true’ sports fan can now (and must now) keep track of his team even during work hours. There’s a specific difference between listening on the radio while working and ‘watching’ through a live web feed — the secondary features call for you to disclose your personal fan preferences, which may then be used by ESPN (or whomever) to better sell you future services, guide you to message boards, and help their advertisers better shill merchandise.

Ultimately, I tend to agree with Andrejevic — we think that we’re getting choices, and our fan ‘needs’ are being better served, but we’re really just opening ourselves up to surveillance, both on the part of the provider and, in many cases, on the part of the employer…who, having become knowledgeable of services such as the ‘boss button,’ may increase surveillance of each worker’s web activity.

As a sports fan and consumer, I found this analysis of ESPN 360 and ubiquitous, internet-based sports consumption fascinating. It is clear from my own experiences that communal interaction has branched out into nearly every facet of sports media. It’s a real triumph for the ESPN model of total immersion that has become the dominant philosophy in other networks and events as well. The desire for sports consumption in all different forms has risen so drastically from where it was before ESPN and the internet that companies are struggling to figure out how to “feed the beast” in a way that will stand out from the clutter.

Workplace sports viewing seems to be the natural next level. In the time since this article was written, ESPN has expanded and rebranded its online service to make it even more essential and accessible, while events like March Madness and The Masters are following close behind. I have many friends who admit to watching sports frequently while on the clock, and the trend has seemed to grow. The brilliance of the ESPN model is that it forces you to keep up with the latest level of sports immersion or else be left behind. For example, Fantasy Sports has grown from a niche market to becoming so widespread that national broadcasts of football games will routinely make mention of it. Viewers who choose not to participate in fantasy miss out on the references and their status in the community is lessened. ESPN makes direct reference to this idea in its marketing of its fantasy website.

In the workplace, ESPN has made sure that it is not adequate for sports fans to discuss last nights events around the proverbial water cooler or even sneak a read of the articles or game updates. Rather, to participate in the sports fan community, one must actually watch the live games presented to them during work hours and, in so doing, submit themselves to the altar of sports fandom at all hours of the day, not just those of their choosing.

Pingback: Foam Finger Cubicle: Selling ESPN360 as Workspace MediaEthan … - Find4Real