Sex and the Postsocialist City

Anikó Imre / University of Southern California

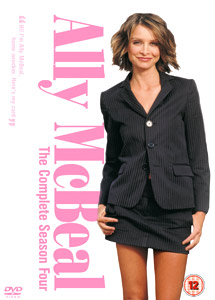

The image above comes from an online ad for the “Guy-Substitute Pillow”. The ad promises that the product provides the closest approximation of an absent man’s arm around a single woman; and she does not even have to endure the snoring! It comes in various colors and fabrics and is easy to order online for a mere $15 or so. I first found the ad on the largest Hungarian fan site for Sex and the City. The HBO show has been at the center of discussions about popular television and (post)feminism, along with other recent quality dramas that revolve around strong, independent women, such as Ally McBeal, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Desperate Housewives or Gossip Girl. In fact, Sex and the City has been called “a key cultural paradigm through which discussions of femininity, singlehood and urban life are carried out.”1 The appearance of independent, often single women in movies and smart quality television dramas has been associated with (post)feminist political empowerment by advertisers, television producers, popular critics and even some academic feminists. Many argue, however, that such empowerment is tempered or undermined by the elitist consumer agency these programs promote. While assessments of postfeminist agency drawn from pop cultural consumption vary from radical skepticism2 through ambivalence (Negra) to affirmation,3 few would disagree that, at the very least, the shift begun by American and British movies and TV shows in the 1990s mix academic and popular strands of feminism. In other words, postfeminism is firmly grounded in and constituted through popular television dramas that perform positive work for young women, who can enjoy their mothers’ feminist achievements but no longer need to pit femininity and feminism against each other.4

Thanks to the global proliferation of American popular culture, particularly television programming, postfeminist ideas and representations now reach much larger populations than did earlier shows that inspired feminist mothers, from I Love Lucy through Maude to The Mary Tyler Moore Show. In postsocialist Eastern and Southern European countries, the formal disappearance of censorship and the absence of economic and political resources with which to resist the European and global push to deregulate resulted in a flood of primarily US television imports in the past 20 years. Postfeminist ideas and images are being disseminated within local national cultures of a defensive patriarchal bent, which have long nurtured a great deal of hostility to feminism. In the Hungarian and, by extension, postsocialist, context, popular postfeminism, imported along with postfeminist television drama, is translated in ways filtered through the local nationalisms of emasculated, peripheral states. Metaphorically speaking, feminist empowerment is limited to a single woman’s financial ability to purchase the guy-substitute pillow when the real thing is not available. While the single woman has emerged in the region in the past two decades, she is hardly a celebrated model of female independence. Rather, she is defined by the absence of strong manly arms that the pillow makes almost sarcastically visible. She tends to be seen as an overworked victim of global capitalism, who has no time to build meaningful relationships with men, which would lead to a fulfilling life as a mother.

As a result, the female-centered storylines of Sex and the City and similar programs automatically reduce them to the position of chick shows, the equivalents of superficial female chatter and glossy women’s magazines, not worthy of serious critical consideration. This is so despite the fact that, while these programs are not carried by national broadcasters, they are very popular locally and possess all the emerging criteria for “quality television”: unique creator-visions, multi-layered storylines and characters, realism, and engaging plots that break taboos and address crucial social issues. Their only significant difference from quality programs that do warrant at least some serious discussion by local critics, such as The Sopranos, House and 24, is their lack of masculine pedigree, most evident in the relative marginality of husband, brother and father characters. As a result, postfeminist quality shows tend to be processed among embarrassed fans in online closets, isolated from discourses that concern the national public sphere.

Reconciling femininity and feminism on a postfeminist terrain is conditioned on a previous discourse of anti-feminine feminism, which was subsequently repudiated in the West as a problematic construct that limits women’s agency. In the East European absence of historical layers of feminism, traditional femininity becomes an excuse not to have feminism at all. It confirms the nationalistic status quo: an essentialist hierarchy between the sexes. In the US and other Western countries, academic feminists have had to acknowledge the fact that popular culture has become a powerful conveyor of (watered-down or even distorted) feminist ideas. However, without a trajectory of academic or activist feminism, East European women, for the most part, are stuck with watered-down, commercialized feminist ideas, which limit agency to good fashion sense. The campy, queer readings of these shows, which are common in English-language reflections, are absent even in the fan commentary, where the programs are re-channeled in a strictly heteronormative discourse.

This is why Ksenija Vidmar-Horvat, in an article that looks at the reception of Ally McBeal among Slovenian women, goes as far as claiming an affinity between postsocialism and postfeminism.5 A strictly consumerist femininity, deprived of feminism’s activist potential, is currently employed to re-legitimate a strict patriarchal nationalism, which is increasingly entangled in a neoliberal culture of consumerism. Feminine desires, encouraged by both consumerist and nationalistic discourses, block, rather than support, feminist desires. In Hungary, postfeminism, much like feminism, crops up in two different kinds of contexts: In the national print and electronic media, one encounters almost exclusively uninformed, distorted, and dismissive views. Postfeminism has been introduced in the mainstream press through the publications of a male critic, Miklós Csejk, who unproblematically calls himself a (post)feminist. His generalized and authoritative pronouncements, offered with an educational air, rely on scanty and questionable sources apparently derived from the French context. He identifies postfeminism precisely in the conservative fashion in which it has been taken up by the anti-feminist backlash in the US since the 1980s. His postfeminism hovers in the abstract, without any historical or geographical anchoring, as if it has by now taken care of all female and feminist concerns everywhere in the world.

The other public context in which postfeminism appears, besides the few new academic gender studies hubs, are self-identified feminist blogs and discussion spaces. Unlike Csejk, however, such discussions do not tend to reference popular culture, most likely out of an understandable fear on the part of the authors over not being taken seriously if they associate themselves with television and other feminized cultural forms. Instead, the discussions revolve around issues of policy, politics and, occasionally, theory. Unlike in Britain or the United States, postsocialist discussions of feminism are isolated from the fan venues formed around Sex and the City and similar programs. Feminists try to claim legitimate space by adopting the high-cultural stance and rational discourse of the national public sphere; whereas “regular” women-viewers’ thoughts and pleasures remain depoliticized and outside the public sphere.

It seems that the missing link between emerging postsocialist feminist groups, who are forced to play the boys’ game and distance themselves from popular representations, and decidedly non-feminist or anti-feminist viewers, whose identities are profoundly affected by the pleasures of postfeminist popular media, is the transcultural study of television. With Vidmar-Horvat, I want to suggest that postfeminism should be used less as a taxonomy of Western discourses around feminism than a global meeting point of cultural discourses around femininity. The growing global popularity and social importance of television provides an excellent opportunity to show that the traditional paternalistic treatment of media audiences and their tastes betrays a nationalistic insecurity. Tracking programs beyond the Anglo-American cultural sphere also makes it possible to broaden and re-activate the gendered roots of television scholarship on a transnational scale.

Image Credits:

1. Boyfriend Pillow

2. Sex and the City

3. Ally McBeal

Please feel free to comment.

- Negra, Diane (2004) ‘”Quality postfeminism?”’ Genders 39, http://www.genders.org/g39/g39_negra.html [↩]

- See Angela McRobbie, “Young women and consumer culture – An intervention.” Cultural Studies 22, no. 5 (2008): 531-550 [↩]

- See, for instance, Amanda Lotz, (2001) “Postfeminist television criticism: rehabilitating critical terms and identifying postfeminist attributes,” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 105-120. [↩]

- Moseley, Rachel and Jacinda Read (2002) ‘”Having it Ally”: popular television (post)feminism,” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 231-249. [↩]

- Vidmar-Horvat, Ksenija (2005) “The globalization of gender: Ally McBeal in post-socialist Slovenia,” European Journal of Cultural Studies vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 239-255. [↩]

Interesting analysis and observations. I’ve recently been paying curious attention to the newer crime/medical shows which have been popping up that portray women protagonist, shows such as Nurse Jackie, Saving Grace, The Closer, and HawthoRNe. It seems that they are making efforts to break out of the “chick flick” paradigm of TV, or in other words, the shows want to be taken seriously rather than dismissed as “women’s TV”. I don’t know how successful this attempt is, but they seem to be marketed as “bad-ass femininity” (or feminine feminism?) intended to appeal to both men and women (or at the very least, shows men can tolerate watching with women). I don’t know how much public discourse these shows will generate (in America or elsewhere) and unfortunately the discussions will be limited to those with cable and premium cable, but nonetheless I find it a curious that these “masculine” genres of crime and medical dramas are portraying strong female protagonists in such a way that does not overly feminize the shows/genres/audiences. Certainly this is not new (as you mentioned Ally McBeal), but it does seem as though the shows are being packaged and marketed slightly different or to wider audiences (for example, I saw a trailer for HawthoRNe while waiting for The Hangover to start). The shows want to be considered quality television rather than relegated to the realm of “women’s tv” and have the potential to spark conversations about (post)feminism.

I agree with the previous poster, but I wonder about the closeted fandom of these shows in Hungary, because despite the professional independence of the female leads in shows such as Sex and the City and Ally McBeal, the major plotlines are entirely concerned with finding and maintaining a relationship or at least sex. I wonder if there is more resistance to these new “feminine feminism” shows as Jacqueline mentions, Nurse Jackie or HawthoRNe, shows that are clearly based around strong female leads, but marketed towards a more gender neutral audience? would there be more patriarchal resistance? do these shows have the same appeal as the previous postfeminist shows?

Thank you, both, for the great feedback. I think it’s certainly true that there are various versions of femininity and feminism circulating in the US, or more broadly English-language, marketplace. It might be that Nurse Jackie et al. actually represent less of a new direction in this respect than do “feminine” quality shows such as SITC. There’s also a generic specificity to the “badass” type, as you say, Jacqueline. The situation is very different in regions like Eastern Europe, though, where nationalism has a strong hold (a stranglehold) on acceptable and desirable femininities, let alone feminisms. It was easier for state institutions, including TV, to sustain this hold during socialism than it is now, in a deregulated environment, where US programs have a powerful appeal. I do think, however, that a local selection mechanism is in place, which screens and channels the reception of new programs, from the acquisition stage through critical reactions. For instance, House and 24 have done exceedingly well in the region, whereas it’s hard to even find Saving Grace, let alone shows like The L Word. Nurse Jackie is too new to have established any kind of fandom. (It’s downloadable, along with subtitles, but shows typically run a season behind on TV.) It will be interesting to compare its reception with that of House, for instance. Clearly, a lot more work to be done.