Justice Is a Bitch: On Damages as a Liberal Revenge Fantasy

Lucas Hilderbrand / University of California, Irvine

Let me just say up front that nothing bores me more than TV procedurals along the lines of Law and Order. So it look a lot of coercion to talk me into watching Damages. To my great pleasure, despite being a lawyer show, Damages cares little for the rules of that genre and, moreover, offers a cynical view of the law as out-of-order. More paranoid thriller than procedural, the show refuses courtroom speeches, and the end-of-season verdicts seem practically irrelevant; it breaks from both the plausibility of “authenticity” and the strictures of the legal process. Instead, it reflects a complete lack of faith in the system and the people who operate within it. Damages is about justice outside the rule of law; it’s a liberal vengeance fantasy that societal harm will be exposed, that knowledge actually does equal power, and that a strong woman can make the powers-that-be (straight white men) pay for their misdeeds.

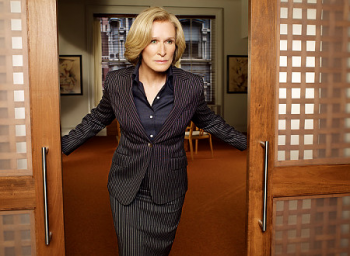

That strong woman, of course, is played by Glenn Close. Damages is perhaps most visible as a star vehicle, but it’s one that taps Close’s savvy and strength from Dangerous Liaisons rather than her hysteria from Fatal Attraction. Close plays Patty Hewes, a class-action litigator who is the kind of character other characters refer to by first and last name, even if they know her. She’s legendary for playing dirty, always winning, and destroying everyone she meets. The theme song, speaking for Patty, repeats, “When I’m through with you, there won’t be anything left.” Yet, she is not a monster; her politics are progressive, and she has a complex personal sense of right and wrong. She doesn’t care, for instance, that her husband cheats on her, but she hates him for being stupid enough to get caught and even more so for betting against her with corrupt investments. The character invites admiration and suspicion, and Close plays her with a kind of shrewd control and superiority—at least until some long pent-up scenery chewing finally erupts near the end of the second season with, for instance, the divaesque line, “I’ve had a shitty month, and somebody’s going to pay”.

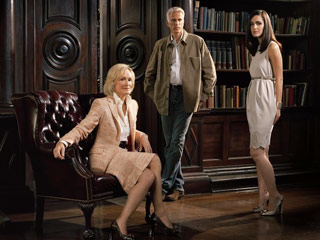

Damages is, in many ways, a revenge plot—of a diva who proves she can carry a TV series in the face of an ageist film industry, of a young lawyer who was nearly destroyed by her boss, and of a liberal who is mad as hell and isn’t going to take it anymore. During the first season, Patty Hewes’ firm takes on a Enron-style tycoon (played by Ted Danson) who has bankrupted his employee’s pensions while profiting enormously himself. To gain access to an elusive witness, she hires new law school grad Ellen Parsons (Rose Byrne), a smart but exploitable subject. The primary arc of the first season is about the ways Patty manipulates and destroys Ellen. In the second season, Patty goes after a company that has been dumping toxic waste and poisoning a small town, and Ellen goes after Patty. Between the first and second seasons, Byrne’s Ellen transitions from an undernourished beauty with a striking emerald trench coat to a far more compelling damaged and pissed off broad. Damages, fascinatingly, revels in transgression for the sake of the public interest.

The show thrives on that early stage of legal work: “discovery.” Knowledge—and the ability to prove that knowledge—is the core of Patty’s legal work. Such epistephilia and dramatic irony are likewise central to the show’s appeal. Without official institutional positions within the boys clubs of the government or corporations, Patty’s power comes from her incisive ability to see through the pricks in power, creatively amass evidence against her defendants, and to bluff when in a pinch. Patty often violates legal process to gain access to privileged information, and likewise the show frequently refuses to play fair the viewer through misleading plot twists. Damages offers a pulpy narrative of teasing flash-forwards, sudden revelations, and dubious reversals—the kind of narrative complexity and manipulation that only television allows. Yet the show strategically refuses the audience the ability to make sense of the puzzle the way other complicated, masculinist serials often offer the satisfaction of narrative mastery; instead, Damages suggests that we, the viewers, can’t possibly understand and that we just have to trust that Patty knows how to win in the end. And part of the fantasy is Patty’s implausible knowledge—that Patty could know so much, could have so many undercover sources, and that she could always be one step ahead of the characters and the audience. When Ellen enacts her personal vendetta against Patty, it’s again primarily through leaking knowledge and betraying confidences as an informant for the feds. Yet, compared to Patty, she’s a novice, and so we wait anxiously for her to be undone.

The pleasures of the text make Damages good TV, but I think the show resonates beyond its clever form. I suggest that Patty isn’t just a fun antihero, but that she is actually embodies a contemporary liberal revenge fantasy. In the post-Bush, post-Enron, post-regulation era, we have repeatedly seen the failure of our government, corporate, and watchdog leaders to act in the best interest of the people. Instead, we have seen conservatives steal elections, mislead the public, abuse power, poison the environment, impoverish the citizenry, and promote the collapse of infrastructure. They fight dirty, and too often liberals have let them. Patty, unethical as she may seem, plays tough, fights back, and is driven to take these kinds of guys down. To quote Tina Fey’s famed Saturday Night Live claim about Hillary Clinton during last year’s primary, “Bitches get things done.” Patty Hewes is a bitch, and she is out for justice.

Damages is not a show about the law, rights, ethics, or morals. It’s not about due process or closing arguments. It’s about justice. For some time now, I have been interested in the tensions between ethics and the law—in the dilemma that they are not always one and the same, that the law can actually fail to serve the public interest because so often it is written to protect special lobbies. Justice, I think, suggests a third category, one that comes into play when neither ethics nor the law have sufficed in guiding actions and when some kind of equalizing retaliation becomes desirable. Obama may have given us hope and begun reform, but conservatives and CEOs still have a lot of atoning to do. Damages offers a retribution fantasy—one that vicariously allows viewers to take pleasure in transgressing legal ethics or due process and that seeks justice from those who’ve so betrayed the American Dream. In the world of the show, Patty demands that corporate crooks and government sell-outs recognize their accountability, and she brings transparency to the ways in which the system can be bought. She strives to punish those in power for what they’ve done, proves that the system needs regulation, and accepts that, if necessary, questionable inside dealing—even violence—may be the way effect progressive change. Of course, as much as we might want our liberal leaders to play a little dirtier at times to get shit done, in reality it would ultimately be difficult to endorse the ends-justifies-the-means model of political process. (It also problematically offers a neoliberal solution to problems caused by neoliberal policies.) That may be why the justice pursued in Damages is so satisfying as a fantasy: through discovery, Patty allows us to know the truth, and through manipulation and litigation, she exacts her—and our—revenge.

Image Credits:

1. Damages on FX

2. Glenn Close in Damages

3. Glenn Close and Rose Byrne in Damages

4. Glenn Close, Ted Danson, and Rose Byrne in Damages

Please feel free to comment.

I agree with presumed link between ethics and the law. The idea that the law is there to “do good.” I think the problem with the law is that it is so often written in black and white. The third category, justice, should incorporate all sides and take all sides into consideration, but instead, you get a hurried document that defends one group and not the other (usually like you mentioned the lobbyist). Two examples would be the Arizona immigration law, and the law currently being disputed in the Senate that would protect the public from large corporation. The Arizona law chooses sides between a group that contributes to the economy but isn’t legalized, and the other group which also contributes to the economy but is legalized (the backlash, even by the Phoenix Suns, shows how see-through this law is). The second law is suppose to grant the federal government the power to dismantle a large failing corporation before it causes irreparable damage to the economy and the public. So why is it stalling? The dispute pins the public versus the corporations. In this world’s capitalistic mindset, competition will always be significant, and in competition, the end result is a winner and a loser.