Just Add Performance

Kiri Miller / Brown University

When I tell people that I’m doing research on Guitar Hero and Rock Band, I usually get one of three responses:

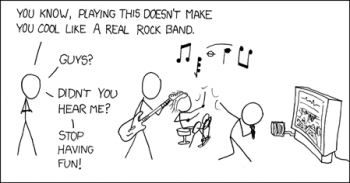

1. “But those games aren’t really musical, right? Isn’t it just pushing buttons in time?”

2. “Are you studying whether they get kids interested in playing real instruments? Because I read an article about how guitar teachers are getting a lot more students since that game came out.”

3. “I love those games! So, do you actually play? Like, for work?”1

People who don’t already have personal experience with the games usually think it’s self-evident that Guitar Hero and Rock Band are only creating musical automatons who suffer from escapist delusions of rock stardom—or, as guitarist John Mayer has said, “Guitar Hero was devised to bring the guitar-playing experience to the masses without them having to put anything into it.”2 If I’m talking to a fellow ethnomusicologist, s/he often assumes that my project involves a critique of the games as the latest symptoms of the decline and fall of genuine musicality and DIY creativity. If there is a saving grace here, it can only reside in the possibility that the scales will fall from players’ eyes and they’ll be inspired to pick up real instruments: in the words of Sleater-Kinney guitarist/rock critic Carrie Brownstein, “[M]aybe by pretending to be in a band, there will be those who’ll find the nerve to go beyond the game, and to take the brave leaps required to create something real.”3

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LnwpfJRea3k[/youtube]

My previous video game project was on Grand Theft Auto, and there, too, much of the non-gamer media response revolved around the relationship between gameworld activities and “the real thing”—only with GTA, the winds of moral panic blew in the opposite direction. Clearly, games like this would inspire players to pick up a real gun or beat up a real prostitute. Think of the children, especially the underprivileged children! As Congressman Joseph Pitts (R-PA) asserted at a June 14, 2006, hearing of the House Subcommittee on Commerce, Trade, and Consumer Protection, “It’s safe to say that a wealthy kid from the suburbs can play Grand Theft Auto or similar games without turning to a life of crime, but a poor kid who lives in a neighborhood where people really do steal cars or deal drugs or shoot cops might not be so fortunate.”4

This kind of “media effects” discourse is so well-established and pervasive that it took Guitar Hero and Rock Band in stride. Will these games save real rock music or destroy it? News at 11!

Come to think of it, Congressman Pitts’s logic might be a more persuasive fit for Guitar Hero than GTA: it does seem more likely that a wealthy kid from the suburbs would have the resources to move from playing a plastic controller to taking private lessons on a Fender.

But really, I think this obsession with the relationship between playing Guitar Hero or Rock Band and playing “real music” is missing the point. My standard strategy for explaining my research to those caught up in the effects debate is to point out that playing these games isn’t just like playing real instruments, but it’s nothing at all like just listening to music. It’s a third thing, a new way of musicking. And if you want to get involved in value-oriented debates about it, here’s a thought experiment: rather than concluding that Guitar Hero players are wasting the time that they would otherwise be putting into long hours of practice on a real guitar, consider the possibility that they might otherwise spend that time just listening to recorded music (or, of course, playing Grand Theft Auto). Anyone who has played Guitar Hero or Rock Band for more than five minutes will tell you that it requires a deeper level of musical engagement than listening to an iPod—intellectually, emotionally, physically, and often socially. Moreover, everyone I’ve interviewed for my research reports that the games have substantially changed the way they listen to popular music when they’re not playing. This has certainly been the case for me; after playing drums in Rock Band I started to hear and understand drum parts in a totally new way (forever altering my visceral reaction to heavy metal, for instance). I’ve been running an online survey about the Guitar Hero/Rock Band gameplay experience, and so far 79% of my 480 respondents have indicated that the games have increased their appreciation for certain songs or genres; 75% have added new music to their listening collections because of the games. (A few more stats appear here.)

My survey statistics only reconfirm what the music industry already knows: these games have created a huge market for value-added versions of previously recorded popular music. Every song licensed for release in the Guitar Hero and Rock Band games has been broken down into parts and transcribed at four different difficulty levels, creating a new, hard-to-pirate digital music product. Once players have bought a game and a set of instrument controllers, and have invested the time required to achieve proficiency on one or more instruments, they are happy to spend money on new repertoire. (This is a venerable business model; in the nineteenth century, once a family had a piano in the house, they gladly kept buying four-hand piano transcriptions of the latest symphonies and chamber music for parlor entertainment.) In March 2009, Harmonix announced that the Rock Band franchise had surpassed one billion dollars in North American retail sales revenue in 15 months, including over 40 million paid downloads of individual songs. In September, Harmonix will release The Beatles: Rock Band, an extraordinary licensing coup—The Beatles back catalog can’t even be purchased on iTunes yet.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPkVNC-h_TE&feature=fvst[/youtube]

The transcription work, scoring mechanism, and on-screen avatar band are the obvious components of the value-added, of course, but I want to suggest that the most important value-added aspect is the potential for performance. Actually, the term “value-reconstituted” might be more appropriate: you reconstitute instant soup by adding water, and you reconstitute a recorded song by adding performance. In both cases, the quality of the original ingredients makes all the difference. Guitar Hero and Rock Band let players put the performance back into recorded music, reanimating it with their physical engagement and performance adrenaline. Players become live performers of pre-recorded songs, a phenomenon that I call schizophonic performance. Unless I’m off-campus, in which case I just call it a lot more compelling than listening to a recording.

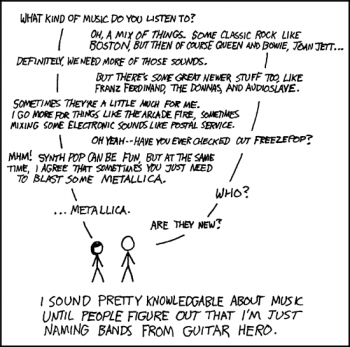

Value-reconstituted songs make some people very uncomfortable, because rock music is supposed to be über-authentic hard work. Instant fame is only for industry-manufactured sellouts, and hitting buttons on a plastic controller to release someone else’s hot guitar solo seems a lot like lip-syncing—it’s not even as authentic as karaoke. But players aren’t deluded; they’re quick to point out that they understand the difference between playing instruments and playing Guitar Hero. (It’s worth noting that 74% of my survey respondents have experience playing instruments; 49% have experience playing guitar). They know that the “instant” songs that they play in Guitar Hero and Rock Band are packaged, commercialized, and designed to be labor-saving, but that doesn’t spoil their musical experience. Just add performance, and the music blooms into new life.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ua3hZXfNZOE[/youtube]

Image Credits:

1. Rock Band

2. Congressman Pitts

3. Music Knowledge

4. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- Yes, I do play, but like everything else that has to do with my research, I can hardly ever make time for it during the academic year—I’m busy replying to student email and attending committee meetings, like everyone else in my profession. [↩]

- Brian Hiatt. “Secrets of the Guitar Heroes: John Mayer.” Rolling Stone Online. June 12, 2008. http://www.rollingstone.com/news/story/21004549/secrets_of_the_guitar_heroes_john_mayer/2. [↩]

- “Rock Band vs. Real Band.” Slate. November 27, 2007. http://www.slate.com/id/2177432. [↩]

- Transcribed from television footage. For further discussion of GTA and the “effects” debate, see Kiri Miller, 2008, “Grove Street Grimm: Grand Theft Auto and Digital Folklore.” Journal of American Folklore 121 (481):255-285. [↩]

Thank you for providing an alternate way to approach these social music games Kiri. I often think a consequence of the popularity of these games (and that they are video games period), there is a dismissal or overlooking of very interesting social effects on players and the music industry as a whole for a rather succinct judgment that they are fluff or without substance. As an avid player of both, I am both interested in the social/communal aspect that the game provides large groups as well as the way it has revitalized and exposed particular genres and specific bands to different generations of music lovers and video game players. On top of that, these games provide such unique and smart forms of marketing for music labels and bands because players begin to learn and memorize the lyrics and the individual musical parts of the song within the game in order to raise their skill level. It really is a phenomena that deserves exploration in a multitude of different areas.

These games provide an way to look at Christopher Small’s “musicking” as an active, social event in a more technological landscape. This both reflects the powerfulness and longevity of Small’s observation and the ability of these games to engage both players and onlookers into a transformative musical space that isn’t a one-way transmission of performance or reception.

A really interesting article Kiri. I really like that you mention the “value-added” concept to these games. One thing that always strikes me about the game play (at least on Guitar Hero) is that the guitar solos, though not entirely “musical” are still difficult enough elements that I believe you gain an appreciation for the formal structure of the solo within the larger song, and the ability to play them requires some form of practice in order to master it.

Anyways, I thought that your approach really adds something to the ongoing dialogue about the social role that these games play, and love that you’ve found something very substantial in your industry analysis.

Colin

Pingback: Tama Leaver dot Net » Annotated Digital Culture Links: June 29th 2009

Thanks Racquel and Colin! You make some excellent points here. I agree that the “practice” component is really important (the vast majority of my survey respondents have used practice mode). In the past couple weeks I’ve been doing more public performance fieldwork, attending Rock Band bar nights in the area. Maybe I’ll write about that in a future column.

Pingback: A MAZE. Festival » Guitar HERO?!

Pingback: Guitar Hero, Rock Band