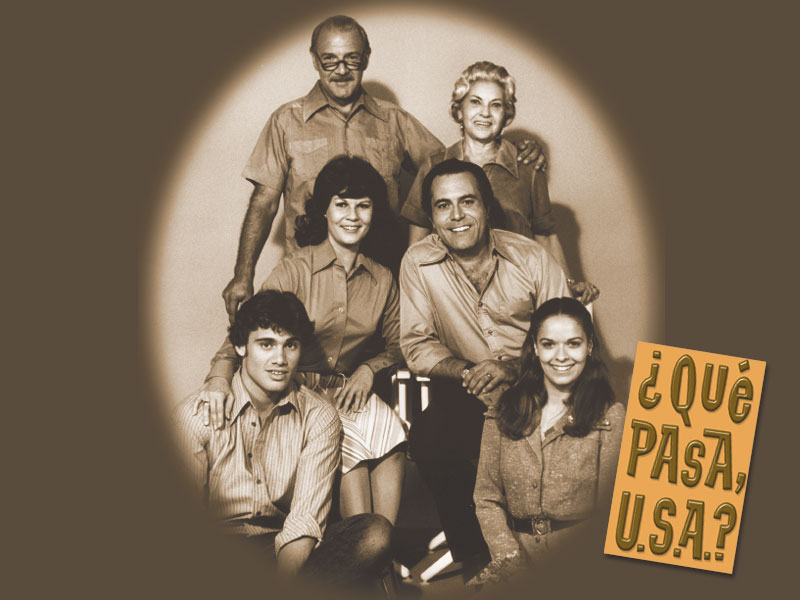

Carla’s, Callie’s, and the Suárez’s Long Lost Ancestors: ESAA-TV and ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.?

Carla Espinosa in Scrubs. Callie Torres in Grey’s Anatomy. The Suárez family in Ugly Betty. The presence of these characters in prime-time programming are the highly visible products of significant transformations of Latina/o representations in US English-language television. Yet, even though I love to watch the kick-ass Tony award winner Sara Ramírez playing a doctor in front of the cameras, I echo Chon Noriega’s assessment: we also need to see changes behind the cameras. As Noriega observes, Latinas/os in Hollywood still have only limited access to positions tied to ownership, production, and decision-making practices.1 This struggle, however, is not a new one, and it seems appropriate and perhaps useful to look back to a federally funded program that intended to open the Hollywood doors to Latinas/os and other minority groups. This program, the Emergency School Aid Act-TV (ESAA-TV), was directly responsible for what should be regarded as the first Latino situation comedy on US television: ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? [What’s happening U.S.A.?]

The 1972 Emergency School Aid Act (ESAA) bill was a governmental intervention to address the legacy of school segregation from the pre-1954 Brown vs. Board of Education era, by eliminating the sustained ethnic, economic, and educational inequalities present in the post-civil right era. Through federal monetary assistance, local school districts with a sizeable minority student population obtained funds to develop educational programs that would help end segregation and discrimination. Besides taking into account race, ethnicity, and class, the bill considered language and culture as aspects that might affect children’s learning environments and their potential sense of isolation.

A minimum of three percent of the ESAA funds were allocated for the development of “ESAA-TV,” educational television programming to promote “positive racial attitudes in children.”2 Using Sesame Street as the primary model for ESAA-TV shows, ESAA-TV was additionally envisioned as on-the-job training for minority media professionals. All the awarded proposals required minority personnel in important positions such as administrators, writers, talent, producers, and project managers. Consequently, ESAA-TV’s secondary purpose was to train a group of minority media professionals who, through working on ESAA-TV, would obtain experience and increase their future job opportunities in the television industry.

ESAA-TV shows were additionally conceptualized as “purposing programming” and as such they were designed to attract particular minority groups in either regional and/or national contexts. For example, ESAA-TV target audiences included Chinese Americans in San Francisco, Puerto Ricans in New York and Connecticut, Mexican Americans in Texas and Los Angeles, Hispanics across the country, Japanese Americans and Vietnamese Americans in Los Angeles, Native Americans in Menominee County, Wisconsin, and African-Americans in Washington, D.C. and Florida. Both regional and national shows had the option of focusing on one or more of the following categories: expression skills, reading skills, cultural programming, bilingualism and biculturalism, and interracial and interethnic tension and conflict resolution.

Reaching the minority target audience was one of the primary objectives of ESAA-TV programming and a major concern for ESAA-TV television producers. As noted in a study sponsored by the US Office of Education, “ESAA-TV series must compete with the high budget, high production value commercial series which do much to condition viewers’ taste.”3 Whereas the phrase “condition the viewers’ taste” suggested a patronizing perspective regarding commercial television’s allegedly faulty citizens/viewers, the issue of market appeal opened the door for a Latino situation comedy on WPBT, the Miami–South Florida PBS station.

¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? addressed the complexities of assimilation endured by the Peñas, a lower-middle class, three-generation Cuban/Cuban-American family. The bilingual, working-class Peña household included the adolescents Joe (born in Cuba, raised in Miami) and Carmen (born and raised in the United States), the adolescents’ parents and the primary income providers Pepe and Juana (born and raised in Cuba), and the adolescents’ grandparents Adela and Antonio (Juana’s parents who dreamed of a return to Cuba). The secondary characters incorporated in almost every episode were Carmen’s best friends Sharon (Irish-American) and Violeta (Cuban-American). The genre’s convention of order, confusion, and restoration of order primarily related to Joe and Carmen’s negotiations between their Cuban and American cultural values; Pepe and Juana’s struggles to keep a balanced Cuban and U.S. educational, social, and cultural environment for their children; and Adela and Antonio’s inability to immerse themselves in the English language–based and totally foreign U.S. milieu.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ctGlsbbJLcM[/youtube]

In its five years of production (1975-1980), ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? explored a variety of socially, culturally, and politically significant themes that included and also transcended the Cuban/Cuban-American Miami community. Over the span of thirty-nine episodes, the Peñas and their friends encountered issues related to the Cuban diaspora in Venezuela, New Jersey, and New York, some Cuban exiles’ obsession with material assets, the community’s racial and ethnic prejudice against other groups, the gay movement and issues of homophobia, the feminist movement, and the emergence of equal opportunity programs. Deemed as one of ESAA-TV’s most critically acclaimed shows, ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? was awarded six regional Emmys and was one of the few ESAA-TV regional television programs to be broadcast on PBS nationally. As a New York Times television reviewer remarked in 1978, “Indeed, it [¿Qué pasa U.S.A.?] puts many commercial productions in the genre to shame.”4

But the enthusiastic reviews and awards were not enough to keep ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? on the air. The ESAA-TV legislation did not require PBS to feed ESAA-TV shows, therefore, only thirty percent of ESAA-TV programming was broadcast on PBS. Yet, even those shows that were picked up by the network were at a disadvantage by being scheduled during what Dr. Dave Berkman, the director of ESAA-TV, described as “toilet time.” Scheduling problems, lack of promotion, and new Hollywood opportunities for some of the show’s actors (Stephen Bauer and Andy García began their careers with ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.?), probably all contributed to the end of ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? in 1980. A couple of years later, President Ronald Reagan’s administration dismantled ESAA-TV.

In the literature on federally funded children’s programming, ESAA-TV has been characterized as an institutional failure. This assessment is based on the project’s lack of financial support and the absence of data indicating whether the shows’ educational objectives were achieved. Although I can understand the basis for these criticisms, I have a different evaluation of ESAA-TV programming. First, ESAA-TV provided once-in-a-(US television)-lifetime opportunities for Latinas/os (and other groups) to work in the industry and produce shows without institutional intervention and with minimal commercial pressures. Second, while I did not have space to elaborate on the other Latino productions (for example, Carrascolendas and Mundo Real), ESAA-TV fostered connections among various Latina/o media professionals without forcing them to construct a homogeneous political, cultural, social, and linguistic “Hispanic” identity.

Certainly, ESAA-TV could be seen as a fiasco in terms of pluralizing television’s workforce and content. Yet, what this piece of US television history demonstrates is that, as Mary Beltrán et al. contend, a combined effort among advocacy groups, guilds, the industry, educators, researchers, and I should add–the government–is needed to transform the ethnic and gender composition of Hollywood’s workforce.5 Until then, we have to pay close attention to what’s happening and what’s not happening on Hollywood’s front stage and back stage.

Image Credits:

1. Carla Espinosa and Callie Torres

2. The Suárez family of Ugly Betty

3. The Cast of ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.?

4. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- Chon Noriega, “Strategies for Increasing Latinos’ Media Access.” Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy 16 (2004): 105-109. [↩]

- Education Amendments of 1972, “Title VII-Emergency School Aid,” P.L. 92-318, 421-442. [↩]

- Bernadette Nelson, Daniel Sullivan, Joseph Zelan, and Susan Brighton, Assessment of the ESAA-TV Program: An Examination of its Production, Distribution and Financing (Cambridge, MA: ABT Associates Inc., 1980), 96. [↩]

- Les Brown, “TV Weekend,” New York Times, June 16, 1978, 22. [↩]

- Mary Beltrán, Jane Chi-Hyun Park, Henry Puente, Sharon Ross, and John Downing, “Pressurizing the Media Industry: Achievements and Limitations,” in John Downing and Charles Husband, Representing ‘Race’: Racisms, Ethnicities, and Media (London: Sage, 2005), 160-174. [↩]

Thanks for a great column Yeidy! It is important to learn about the historical lineage to today’s television Latinos. I find fascinating that the federal government funded “a program that intended to open the Hollywood doors to Latinas/os.” Interesting also is the fact that Cubans were chosen to represent the Latino lot in the US at that time. It seems to me this is representative of issues relating to “model” Latino citizens versus those ‘Others’ (such as Puerto Ricans, Mexicans) who according to people like Linda Chavez (1991), refuse to assimilate. I agree with your conclusion, that it will take a combined effort to transform Hollywood’s current composition.

Hilda, thanks for your comments. One thing to keep in mind is that Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans also had their own shows. What pushed ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? to PBS nationally was the quality of the sitcom. Although I recognize the subjective nature of “quality,” critics at the time praised the show’s production. My own assessment is that the acting, the scripts, the direction, and the overall production are superb. Part of the show’s success related to the extensive television experience of many of the people who worked in the production. Some of the creative and technical staff began their careers in Cuban commercial television. For example, Velia Martinez, the actress who played the grandmother was a well-respected television actress in Cuba during the 1950s. Regarding assimilation, in a longer piece (maybe published in 2010…not sure) I argue that, in fact, the main goal of ¿Qué pasa U.S.A.? was assimilation. Another objective was to challenge the discourse of a singularized middle-upper class and Cuba-centric Cuban Miami community. If you have not seen the show, I highly recommend it (and you might find episodes online). And, if you are interested, as soon as the longer piece is published, I will be happy to send you a copy.

I am interested in reading the longer piece once it is published. You can email it to me at hilda.llorens@gmail.com

Gracias!

Its a Great news, that Latino are being presented on this platform to express their views. More good news is that, Fed Government is encouraging by many means. I hope this may continue, so that Latino community can express their problems on broader spectrum.cisco exams