You’re Fired! Reflecting the Economic Crisis in the Business Entertainment Format

Lisa W. Kelly /University of Glasgow

Together with my colleague Dr. Raymond Boyle, I have recently begun working on a two-year project researching representations of business and entrepreneurship on British television and, given the current economic climate, it seems very timely. With the fifth series of The Apprentice back on British screens (and The Celebrity Apprentice showing in the US), questions have been raised about the appropriateness of the show and its slogan ‘You’re Fired!’ during a period in which large numbers of people are struggling to keep their jobs in the real world.1 Even more problematic is the type of culture it celebrates; the cutthroat, ruthlessly competitive, ‘Winner Takes It All’ mentality that sees the BBC trailer for the series drawing on the Abba song of the same name and which has led journalist Polly Toynbee to suggest that it was exactly this type of behaviour ‘that got us into this mess in the first place’.2 Yet, the first episode of Series Five attracted record viewing figures (8.1 million viewers tuned in, securing a third of the available audience) and the rhetoric surrounding the series has focused on how it aims to reflect the credit crunch by freezing its production budget and going back to business basics. This means that rather than travelling abroad for one episode, to the exotic climes of France or Morocco, the candidates’ skills will instead be put to the test in the seaside town of Margate where they will be charged with reinvigorating the town as an attractive holiday destination.

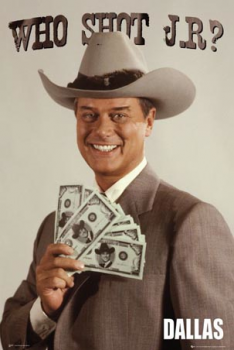

It will be interesting to see whether this current wave of public opinion will result in a sea change in the types of representations of businesspeople and entrepreneurs found on our TV screens. After all, as recently as the 1980s, British attitudes to wealth creation and big business were mostly negative, and businessmen (as they did tend to invariably be men) were depicted primarily in drama and comedy programming as either suspect and untrustworthy or mere figures of fun.3 While British examples of this include Arthur Daley in Minder and Del Boy from Only Fools and Horses, one of the most globally recognisable from this era is, of course, J.R. Ewing from the American prime-time soap Dallas, suggesting that American attitudes were similar. Indeed, in a study by Lichter et al. analysing the portrayal of American culture in prime-time television from the 1950s to the 1980s, the authors’ found that businessmen were ‘three times more likely to be criminals than [ ] members of other occupations’ and that their crimes tended to be ‘either violent or sleazy’.4 With the dawn of the 1990s however, public attitudes to business, entrepreneurship, and wealth creation began to change, as did their respective representations on television. Although there is no room to discuss this in detail here, advances in communications technology and the dotcom boom led to a sense that anyone could start their own business (even if this was not always acted upon) and the emergence of social and creative entrepreneurship meant that ethics and profits were no longer regarded as being mutually exclusive. While news and current affairs has always engaged with the world of business, entertainment-driven television also began to understand the benefits of this area. Providing risk, jeopardy, and, more crucially, stories that viewers could relate to about the everyday decisions and pressures involved in running a business, the rise of the business entertainment format soon took hold.

In Britain at least, this can be traced to the successful series of programmes produced in the early 1990s by Robert Thirkell at the BBC Business Unit. Troubleshooter, Trouble at the Top, Blood on the Carpet, and Back to the Floor each took a particular focus on businesses and the people who run them. While the latter (in which bosses returned to the shop floor to experience the problems besetting their workers first hand) drew on the docu-soap aesthetic that was popular at the time, it was perhaps the first of these, Troubleshooter, that has been of most influence within the industry, as shows such as Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares and Mary Queen of Shops follow the format of sending an expert (from the restaurant and retail trades respectively) into failing or underperforming businesses with the aim of turning them around. Yet, the business entertainment format has also diversified to quite an extent in the last decade or so. Not only has lifestyle programming been merged with business, in the manner of Property Ladder, but numerous programmes about entrepreneurship have also arisen, including Risking it All, Make Me a Million, and The Secret Millionaire. Two of the most original formats to have been developed are The Apprentice and Dragons’ Den, with the former introducing a competitive game element to the interview process and the latter involving pitching to a panel of ‘dragons’ for capital investment.

It remains to be seen how The Apprentice will fare in this economic climate, as although the backbiting and rampant individualism of the contestants appears to be out of step with the times, the show can also be considered primarily in entertainment terms, in which viewers are encouraged to laugh at the constant ineptitude on display (there is also perhaps a cathartic element to this in that the series reflects the kinds of inadequacies exhibited by the city bankers who Toynbee blames for getting us to where we are today and who have since, in some instances, experienced the words ‘You’re Fired!’ first hand). The focus on helping small businesses in Dragons’ Den on the other hand, is in keeping with the notion that it is innovative entrepreneurs who will help lead us out of the economic crisis. With the show’s production team descending on a support exhibition for start-up companies in Glasgow in the hope of finding potential entrepreneurs seeking investment, Ceri Rogers from New Start Scotland highlights how ‘75% of Scottish new starts have been refused funding from the banks over the past 12 months so investors like the Dragons are crucial in helping SMEs struggling to survive the economic downturn’.5 While the rhetoric surrounding the series emphasises the fact that the Den may be one of the few places left to go for funding, the logistics are that of the thousands seen at the regional auditions, only a small minority will make it onto the show and even less will secure the investment they require. Nevertheless, Dragons’ Den has the chance to offer a more positive spin on its engagement with the recession than its counterpart The Apprentice.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfUuD54IuHs&feature=related[/youtube]

I want to end by briefly noting that a new area of business programming seems set to flourish in the current climate and it is that which revolves around philanthropy. Only a few short months ago in an article for Flow, I questioned the impact that the Channel 4 series The Secret Millionaire could have on society due to its focus on the eponymous millionaires rather than the ordinary people carrying out admirable work within their communities or living in poverty. While I still think the show is problematic, the latest series to be broadcast on British television appears to have come at just the right time. With news reports focusing on protestors smashing the windows of Sir Fred Goodwin’s house, due to the former Chief Executive of the Royal Bank of Scotland’s refusal to part with any of his £16 million pension (despite presiding over the bank’s collapse),6 the sight of wealthy individuals giving something back in The Secret Millionaire provides a welcome antidote to the narratives of greed dominating the press. Perhaps the last word then should go to the multi-millionaire businessman and former boss of Rover, Kevin Morley, who described the prospect of giving away a quarter of a million pounds on the show as ‘the most exciting day of my life so far’.

Image Credits:

1. Donald Trump on The Apprentice

2. Del Boy embarks on another money-making scheme in Only Fools and Horses

3. The villainous J.R. Ewing in Dallas

4. Front Page Image

Please feel free to comment.

- It has also recently been revealed that an Endemol series called Someone’s Gotta Go is in production for the Fox network in the US, although no details have been released as to when it will be screened. The premise of the show is that each week the focus is on a small business that is faced with making someone redundant due to the current economic downturn. With company bosses revealing how much each person earns, employees will then have to vote on who should be added to the rising unemployment figures. ‘Someone’s Gotta Go: Reality Show to Lay Off Employees’ in The Huffington Post (08/04/09) URL: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/04/08/someones-gotta-go-reality_n_184668.html [↩]

- Newsnight, BBC2 (25/03/09). [↩]

- Jack Williams, Entertaining the Nation: A Social History of British Television (Stroud: Sutton Publishing 2004), p. 61. [↩]

- S. Robert Lichter, Linda S. Lichter, and Stanley Rothman, Prime-Time: How TV Portrays American Culture (Washington D.C.: Regenery 1994), p. 211. [↩]

- Ceri Rogers, New Start Scotland (23/03/09) URL: http://www.newstartscotland.com/newstart/index.php?action=view&id=202&module=newsmodule&src=%40random46c1ce833e604 [↩]

- Lindsay McIntosh and Martin Waller, ‘Sir Fred Goodwin’s £3m home attacked by vandals’ in Times Online (25/03/09) URL: http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/industry_sectors/banking_and_finance/article5972737.ece [↩]

This is a really interesting wave to be riding at the moment Lisa. Good luck with this. You’re hired.

I was interested in particular in your comments on the ineptitude of the contestants in ‘The Apprentice’, and the image that this presents to me about the nature of expertise, skill and integrity that this programme offers in relation to that of the cut-throat entrepreneur. This is particularly pertinent in relation to the fact that Sugar (or is it Nookie Bear?) is the weathered face for a UK Govt promotion of actual apprenticeship schemes.

On one hand, there are parallels here, for the UK at least, between these TV figures and those kinds of bosses who have headed firms without any kind of relevant qualification or critical faculties at all.

Watching (the highly enjoyable) episodes of ‘The Apprentice’ as they unfold, I am repeatedly struck by the manner in which the show exposes how competitors have absolutely no interest in the products that they originate, market and sell. Nor is there any investment in the various skills with which products are invested and which we are told about in wider advertising campaigns and mythologies (Laboratoir Garnier, Sports Science et al). Is there some kind of ‘rupture’ going on here concerning the nature of totemic commodities – their worth, what goes into them and the nature of labour and what that word means or might mean? Too many cooks perhaps…

I wonder whether the boss as hero (Sugar as celebrity for instance) is part of your remit? You might be interested to note here that Raphael Samuel long ago wrote on this phenomenon in New Left Review (about 1960 I think) – not that I’m that old).

Hi Paul, Thanks for the Samuel reference. We will definitely be considering the narratives around entrepreneurship, with the ‘boss as hero’ being one.

It’s also interesting what you say about bosses who head firms without any seemingly relevant qualifications. The appointment of Gerry Robinson as Chief Executive of Granada in 1991 springs to mind here. While this went down well with shareholders, due to his business reputation of cost-cutting and putting profits first, television creatives were not so impressed with his lack of experience of working within the medium and his confession that he knew nothing about Granada, beyond having seen Coronation Street (leading John Cleese to label him ‘an ignorant, upstart caterer’). Since then, of course, Robinson has become a familiar face in front of the camera producing ‘troubleshooter’ type shows in which he tries to turn around failing businesses. It seems that there may be a link here between the move, in the 1990s, to make television operate more as a business and the increase in business-related programming on our screens now.

I forgot that you had mentioned Secret Millionaire which is so curious amongst all of this ‘genre’ in its treatment of the boss as philanthropist. There is some social investigation, trsnformative TV style trasnformation (for some of them) and a softening of the harder edge of the image.

A lot of execs could learn a thing or two by watching Celebrity Apprentice

Pingback: Can Mark-Paul Gosselaar’s Marriage Be Saved by the Bell? | what is happening now.

Really Inspirational