Life on Mars as Seen From the United States: The Cultural Politics of Imports and Adaptations

Serra Tinic/ The University of Alberta

Excerpts from IMDb message boards:

“[T]his is America we are talking about, the U.S.A. and we don’t care about our Canadian and Mexican neighbors so why would we care about English shows (collectively, not me). … And we are generally too self absorbed and parocial (sic) as are all empires in their hey-day to want to watch a lot of directly imported British TV. Though for some reason we are on a big kick of hiring Brit actors to be in American shows and do fake, but nearly flawless American accents.” – lisamj1973 (January 3, 2008, Thread: “Life on Mars 2006”).

“I guess the fans of the Brit show are happy now. You all remember them? The ones who were here at the beginning of the season swamping this board with how horrid the show was and how ABC ‘had no right’ to destroy the memory and image of the great Brit series with this ‘American Schlock’ … ripping every detail apart in a second by second comparison of the minutiae of sets, actors, lines, music, ad infinitem; ad nauseum.” — sevenof9fl (March 18, 2009, Thread: “I guess the fans of the Brit Show”).

“This isn’t a ‘US is evil’ type thread. Just stating the obvious. If their TV can travel across cultures, then so can those from Australia, England and wherever … And just being more trusting of non US shows will breakdown the insular attitude of the nation.

— justin_leebrigs (April 16, 2007, Thread: “Life on Mars 2006”).

“I am from the US and I prefer the UK original in pretty much every aspect: setting, themes, characterization, actors, drama, humor, and so forth.” — kinokima (March 12, 2009, Thread: “Life on Mars 2008”).

When ABC announced that it had purchased the rights to develop a domestic adaptation of the award-winning BBC drama, Life on Mars (2006-7), the network sparked a transnational audience debate (at times a feud) throughout the blogosphere and on newspaper message boards. Invocations of ‘cultural imperialism’ were common and even American television critics were concerned that ABC’s version (LoMUS) would be another example where, “American networks took good British shows and removed all the stuff that made them good.”1 As the above comments indicate, the salience of the ‘aura’ of the original was at stake. At a broader level, however, a transatlantic audience dialogue developed that explored the boundaries of cultural difference in a global television environment as well as the divergent national industrial practices that structure drama production. This column provides a mere sketch of the issues raised by the domestication of Life on Mars and situates them within the current challenges facing the mainstream American broadcast networks.

Life on Mars is the story of Manchester DCI Sam Tyler (British actor John Simm) who, following a car accident in 2006, awakens to find himself as a detective inspector in 1973. Tyler is uncertain as to whether he has traveled through time, has gone insane, or is in a coma. His sense of dissonance as a new millennium detective in a by-gone era of police practices allows the series to explore the socio-cultural specificity of the politics of race and gender in 1970s Britain. However, LoMUK operates on multiple levels for its domestic audience. It is simultaneously a crime procedural with science fiction undertones as well as a nostalgic portrait of the styles and music of the decade. Moreover, it speaks to the nation’s television history as an intertextual reference to 1970s crime dramas, most notably The Sweeney (ITV 1975-8), which depicted the darker side of urban British policing. For the series’ fans, this rootedness in a particular space and time(s) made it unimaginable for Tyler to be merely transplanted into an American context. And the American version, originally set in Los Angeles, was beset by creative conflicts from the beginning. The show’s executive producer David E. Kelley left; the setting was moved to New York; and the only remaining cast member was Jason O’Mara as the lead, Sam Tyler. Casting proved to be such a challenge that the new U.S. production team contacted Philip Glenister to reprise his role as the politically incorrect DCI (now Lieutenant) Gene Hunt. Glenister, however, had already signed on to the British sequel, Ashes to Ashes.2 This invitation, combined with the fact that the first seven episodes of LoMUS were practical carbon copies of the BBC series, inevitably led British audiences to question: why not just import the original?

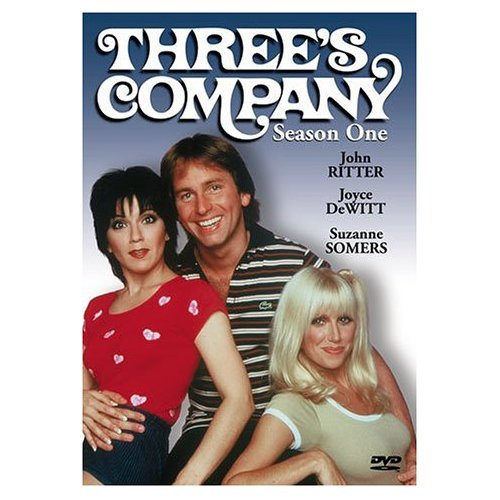

The answer to that query lies in the economic objectives of the American broadcast networks as well as executives’ conventional imaginings of their target audiences. In regard to the first, LoMUK was a limited-run production of 16 episodes over two series (“season” in American television). While limited-run series are common in most national television industries, they do not meet the need of American broadcast networks to produce a sufficient number of episodes for future syndication. Ironically, with the cancellation of LoMUS a few weeks ago, the American version became a de facto limited series with only one more episode than the original. The second component addresses the risk-averse nature of the American networks and their common-sense ideologies of the cultural competencies of domestic audiences. The “heartland myth” that Victoria Johnson so aptly describes, prevails in programming decisions despite the increasing fragmentation of audiences across media platforms and subscription channels. Victoria E. Johnson (2008).3 The construction of an imagined mid-west/populist touchstone that stands in for the unknowable audience reinforces the industry’s assumption that any series set outside of the United States will simply be too foreign or alienating for the target market. From Hollywood’s perspective, 1973 Manchester truly is Mars. The history of successful domestic adaptations also serves as a self-fulfilling industrial prophecy. Throughout the 1970s some of the most popular American comedies on network television were direct remakes of British originals: All in the Family (Till Death Us Do Part), Three’s Company (Man About the House), Sanford and Son (Steptoe and Son). The success of one of the few direct imports, The Avengers, illustrates the lapse in institutional memory. As Miller notes, part of the popularity of the series during its network run on ABC (1966-7 and 1968-9) was attributed to its capacity to represent a particular imagining of “Britishness.”4 Avengers aside, however, most original British television was relegated to PBS.

The rigid national boundaries of American network television have changed dramatically since the days of All in the Family et al. With the advent of various torrent and p2p video-sharing sites, audiences now have access to both original series and their adaptations at virtually the same time. They are also available in more legitimated satellite and subscription venues such as BBC America (albeit edited for commercials). Therefore, I want to conclude this cursory analysis with a series of questions about the future of U.S. domestic adaptations — both as cultural productions and topics of academic study. To date, most of the scholarship on format adaptations has examined the hybridization or glocalization dimensions of reality television, makeover programs, and game shows. Studies of adapted scripted drama and comedy, such as Griffin’s analysis of the American version of The Office, provide excellent details of how a series can be ‘made to work’ for international audiences but there remains a gap in our understanding about what this means for national audiences in the original broadcast market.5 The reactions of British fans to LoMUS indicate a different depth of cultural resonance and ownership of television drama than we might expect for Big Brother or What Not to Wear. In this respect, imitation may not be flattering but rather seen as an appropriation by a more dominant cultural player. Here, fictional television series can still be seen as belonging to the particular experiences of space and place. Questions of cultural proximity are also brought to the forefront: how foreign is too foreign in the containment of difference? I’ve attempted to introduce these issues through the example of Life on Mars (as opposed to a series such as Ugly Betty) because the drama would appear to meet the dominant language and genre requirements of the American broadcast networks.

The economic challenges currently confronting the American broadcast networks may provide an impetus for change. It was only a few years ago that Canadian television series set in actual Canadian cities were considered too foreign for American audiences. In 2004, amidst great trepidation, CBS purchased the Vancouver-based crime procedural Da Vinci’s Inquest to address the dearth of syndicated scripted drama that had resulted from an over-reliance on reality programs. Produced within a national public broadcasting system (CBC), Da Vinci more closely resembled the British Cracker than it did most American crime dramas. It also defied the network’s conventional wisdom about imported programming by showing the greatest percentage of audience gains among its competitors in off-network programming.6 In fact, the relative success of the series encouraged American networks to look at imported Canadian programming as an insurance policy during the WGA strike. CBS’s purchase of Flashpoint, which won its market in primetime as a summer replacement series, prompted the other networks to follow suit. Together CBS and NBC will directly import five new Canadian series for 2009-10 as they continue to cut production costs in a softening advertising market. Could the new trend to air imports extend to other countries? Canadians with their indistinguishable accents may be able to pass as Americans but that did not initially overcome the ‘cultural discount’ that was seen to define programs explicitly set in Toronto, Vancouver, or rural Saskatchewan. If this discount no longer applies, can imports of television series set in Slough or Manchester, UK be far behind? The corollary to the headiness that has accompanied the recent success of Canadian imports to one of the world’s most restricted markets is the expressed concern that domestic producers will now cater to the cultural appetites of the American broadcast networks. But that is a topic for another time.

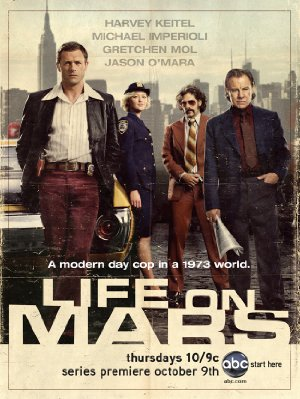

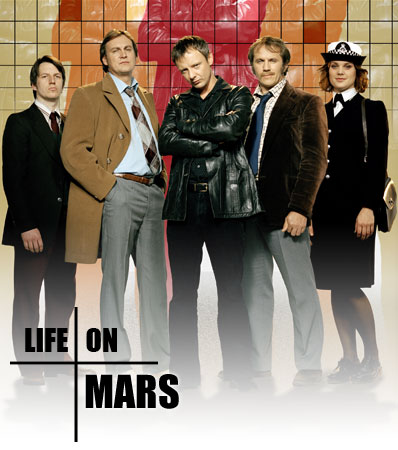

Image Credits:

1. Life on Mars (US)

2. Life on Mars (UK)

3. Till Death Us do Part

4. All in the Family

5. Man about the House

6. Three’s Company

Please feel free to comment.

- Maureen Ryan (August 5, 2008). “The New ‘Life on Mars’ – Is this ‘Journeyman,’ take 2?” http://featuresblogs.chicagotribune.com/entertainment_tv/2008/08/american-life-0-html [↩]

- Laura Collins, (October 26, 2008). “Phil, baby, it’s Harvey Keitel. How am I gonna follow your DCI Hunt?” http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-1080583 [↩]

- Heartland TV: Prime Time Television and the Struggle for U.S. Identity. New York: New York University Press. [↩]

- Toby Miller (1997). The Avengers. London: BFI. [↩]

- Jeffrey L. Griffin (2008). The Americanization of The Office. Journal of Popular Film and Television 35(4): 154-63. [↩]

- Christopher Lisotta (2006). Program Partners Syndicates Canadian ‘Crime Watch’ Block. Television Week 25(16): 28-30. [↩]

Thanks for such a thoughtful piece on Life on Mars, Serra. You may know that here, in Australia, we get to watch both the UK version of LoM AND the US version on free to air. It goes without saying that there is no Australian version. Similarly, but importantly differently, we not only get to watch the Australian, original, version of Kath and Kim but also the US version, both, again, on free to air. The UK, I understand, got to see the Australian version, which, perhaps, tells us something about the continuing belief that Britain and Australia are culturally closer than the UK and the US–though it might just tell us about the marketing arrangement between the BBC and ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Watching the American version of Kath and Kim in Australia is a little unsettling–perhaps I should say uncanny. The familiar is made unfamiliar but remains strangely familiar while we are so used to watching American series here that, in a disturbing way, the unfamiliar is actually almost more familiar.

Back to LoM. One thing that intrigues me about the series, which is fundamental to its structure, is its nostalgia. You rightly point out the UK version’s relationship to The Sweeney. For the US, I suppose that the referent would likely be Starsky and Hutch–though that series did not have the darkness of LoM in either of its incarnations. At the same time, I strongly suspect that one element in the UK version’s popularity was that, for many baby-boomers, the show portrayed a lost world; a world when West Indian and South Asian migrants were still just that, migrants, and a world before Thatcher and the complexities of neoliberal globalisation, let alone a world before mobile phones and the net. At the same time, the hook of the show is that it retains a link with the ‘present day’, so viewers don’t need to feel too guilty about wallowing in a fantasised past. LoM, with its Bowie reference, is part of the nostalgia industry, like those endless remastered with extra tracks CD reissues of 1960s/70s albums, that feeds off the aging baby-boomers, and their pre-retirement wealth (well, before the global financial melt-down!!).

A great piece. I love that you highlighted the issue of other, seemingly canonical US tv shows having their origins in the UK and transplanted to the US.

One thing that intrigues me about the US version of Life on Mars is not only the issue of nostalgia, which is pretty huge, but the show’s initial reference to the World Trade Center towers in episode one.

Having seen the entirety of both shows, this initial image makes the first episode particularly resonant, especially as the rest of the episode is pretty much a shot for shot remake of the original. I wonder if this makes the series (and nostalgia for a pre-9/11 New York) more or resonant resonant.

Speaking more to your article, I wonder what you make of Jason O’Mara’s casting (a Brit playing a New Yorker in a transplanted British show) and further, the trans-national (and seemingly pretty Canadian) composition of most prime-time shows in the US (Howie Mandel, Kiefer Sutherland, Sandra Oh). It seems as though Canada is not only exporting its shows (as you refer to), but definitely a lot of its talent.

Pingback: who’s that girl?: Life on Mars and the Test Card Girl « Act Your Age

You’ve raised some very interesting points here, many of which have become all the more problematic recently (I’m thinking about the level of advertising currently being heaped upon the latest incarnation of Doctor Who, which is finally being broadcast on BBC America in parallel with the UK run). Whenever I watch shows such as Spaced, and, more recently, The IT Crowd, I am typically struck by the degree to which American culture has managed to permeate these texts, whether this manifest itself as references to classic children’s animated series such as Scooby Doo, Where Are You! in the former, or the more oblique incorporation of indie-rock music by groups such as Guided By Voices in the latter. You hint at the fact that many fans of Life on Mars were upset by the remake because there seems to exist a certain irreproducible cultural specificity at play in the original version. To a large extent, I think you’re correct. It has always amazed me that, although Life on Mars seems to riff on shows such as Starsky and Hutch, among others, the nostalgia inherent within the premise of the show remains firmly rooted to questions of Britishness (for instance, I cannot think of a single example in which an American pop song is used, etc.). This tendency, I feel, raises some issues regarding the reactionary status of the text as a whole, perhaps more obviously explored through Sam Tyler’s perpetual debate with Gene Hunt regarding his antiquated methods of police investigation.

Pingback: Sharing a laugh? | tvkulturer