Orientalized Masculinities in Contemporary Australian Cinema

Jane Park / The University of Sydney

On my final night in the U.S. before moving to Sydney last year, I finally got around to watching Romper Stomper. While Geoffrey Wright’s film about Aussie skinheads didn’t provide the most cheerful picture of my soon-to-be new country, I was struck by its viscerally engaging style and its representation of Asian characters. As many critics noted upon its release in 1992, Romper Stomper sucks viewers in with its active camera and pumping soundtrack, positioning us, albeit ambivalently, alongside the skinhead youth whose story is clearly foregrounded. Unsurprisingly, few critics had much to say about the role of the peripheral Asian figures that frame the movie: the Vietnamese immigrants in the opening who are beaten up by the white supremacist gang and soon avenged by angry members of their own community and the impersonal Japanese tourists in the end who snap pictures of the gang leader as he is being murdered on the beach by his best mate.

These framing scenes provide iconic images of two forms of Asian presence in contemporary Australian cinema. The first is that of the Asian tourist (usually Japanese) who is welcome as long as she or he ultimately returns home. As Asian Australian film scholar Olivia Khoo convincingly argues, this figure must die if she or he stays in Oz, functioning ideologically as a necessary sacrifice used to further the inner development of the white protagonists.1 The second image is that of the Asian immigrant (usually Vietnamese, Chinese or Lebanese) who, depending on the context, embodies either an economic and cultural threat to the (implicitly white) Australian nation or reaffirms its tolerant multiculturalism. Much like the dialectical binary of the model minority/gook articulated by Asian American historian Robert Lee, both positions render the racialized immigrant a conditionally white citizen who is expelled or otherwise punished as a foreign contagion as soon as she or he threatens to usurp the privilege of those in power.2

What really surprised me is the central role that these iconic figures play as love interests to Anglo-Australian women in two fairly recent commercially successful and critically acclaimed Australian films. In Sue Brook’s Japanese Story (2003) Hiromitsu, a Japanese businessman enthralled by the outback has a (literally) short-lived affair with Sandy, an urban professional forced to be his chauffeur who herself is out of place in the harsh and stunning landscape. And in Rowan Wood’s Little Fish (2005) Vietnamese Australian drug dealer Johnny returns to Australia, ostensibly gone straight after a few years in Canada, hoping to resume his relationship with ex-junkie Tracy, who is trying unsuccessfully to start her own business in Cabramatta, the “Little Saigon” of Sydney.

As I discuss in my forthcoming book, Asian men rarely appear as romantic partners for anyone, and especially white women, in Hollywood cinema due to still prevalent stereotypes of the feminized, desexualized or otherwise emasculated Asian male in the U.S.–stereotypes rooted in the history of Chinese male immigrants who were systematically ghettoized, forced to take feminized domestic jobs, and prevented from forming families thanks to anti-Asian exclusion laws.3 For this reason, I was interested to see how a romantic relationship between an Asian man and a white woman would play out on the big screen in Australia, a Western nation in the Pacific that draws culturally on Britain and the U.S. and economically on its Asian neighbors.

Sadly, both films fell short of my perhaps unrealistically high hopes. Outside the radical acknowledgment that Asian men might actually be desirable to white women, Japanese Story and Little Fish use the same tired tropes and techniques to represent sympathetic Asian characters as selfless “caregivers of color” to borrow Cynthia Sau-ling Wong’s phrase and thus unwittingly reveal the power hierarchies that continue to structure white fantasies of the exoticized and eroticized Asian “other.”4

The new twist on an old formula is the clever way in which these films successfully masquerade as anti-racist, colorblind narratives. Japanese Story appeals to white liberal audiences by showcasing the development of a taboo interracial relationship between a white woman and an Asian man, which can only happen in the liminal space of the road and the indigenous wilderness. While the film is beautifully shot and there are some funny and poignant moments of connection between the characters, it is difficult, as a Korean American female viewer, not to notice the blatant ways in which Hiro is orientalized, functioning as the compliant male Lotus Blossom for the ambiguously butchy Sandy, who seems to see in his smooth skin, lean physique, and poor English an alternative, more manageable masculinity to that of the big, loud, and dismissive Australian men who ignore her throughout the film. No surprise then that she dominates her submissive Asian lover in bed, literally putting on his pants before she mounts him in their first sexual encounter. Hiro takes the traditional position of the woman in the scene: he remains absolutely still as the camera follows her gaze to look down at him. Tellingly, when he finally takes sexual initiative, kissing her rather than being kissed, he unexpectedly and inexplicably dies after following her playful instructions to jump into a lake.

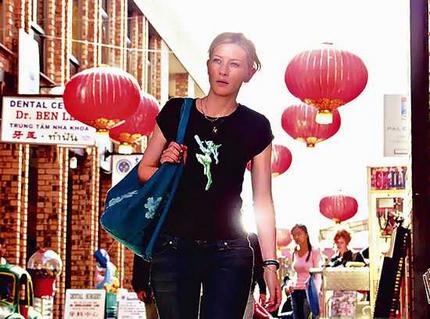

In contrast Little Fish plays down Johnny’s racial difference even as it consistently plays up his cultural difference as a hybridized Vietnamese Australian. None of the Australian reviews I read of the film discuss the interracial aspect of the romance between Tracy and Johnny, and while most comment on its “authentic” setting, the implicit connections between the Vietnamese immigrant community and its association with drugs and gang violence is not discussed because, as my Australian colleagues informed me, this is already a given for the target audience of the film–most of whom would never venture into Cabramatta except for the occasional food tour. Likewise, the racial and cultural difference that Johnny embodies and that constitute the backdrop of Tracy’s working life is coded implicitly as a contagion, much like the drugs that form the central motif of the film. Tracy is still, it seems, addicted to the dangerous drug that is Johnny. Her family warns her to stay away from him yet she compulsively calls him (and he always comes running) only to flee from him for no discernible reason. On a more positive note, Johnny unlike Hiro, takes a more equal role in lovemaking and amazingly lives to see the end of the movie. I suppose that is something to celebrate. Yet I can’t help but feel a bit sad and perplexed that at a time when so many Asian countries have entered First World status, a mixed-race man is president of the United States, and the Australian prime minister speaks Mandarin, this is what we can claim as progress for representations of Asian people on the big screen.

Image Credits:

1. Lovers Sandy and Hiromitsu in Japanese Story.

2. How do Australian screens represent the masculinity of the Asian male?

3. Tracy in Cabramatta.

4. Addictions and contagions.

Please feel free to comment.

- Khoo, Olivia. “Telling Stories: The Sacrificial Asian in Australian Cinema.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 27 (1-2): 45-63. [↩]

- Lee, Robert. Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999. 180-204. [↩]

- Yellow Future: Oriental Style in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming 2010. [↩]

- Wong, Cynthia Sau-ling. “Diverted Mothering: Representations of Caregivers of Color in the Age of ‘Multiculturalism” in Glenn, Evelyn Nakano, Grace Chang and Linda Rennie Forcey, eds. Mothering: Ideology, Experience, and Agency. New York: Routledge, 1994. 70. [↩]

Hey Jane,

I am intrigued by your ambivalence on Tracy and Johnny’s relationship. I think that biological warfare had always been an important ingredient of manifest destiny. Within that context, the mutual contamination and survival of Tracy and Johnny’s relationship become a metaphor signaling that Asians in Australia have now been “vaccinated” against white supremacy and therefore fully integrated. Consequently, contamination works as an integral part of national integration. What do you think?

The Masculinity of the Asian Male in Media

The article, “Orientalized Masculinities in Contemporary Australian” by Cinema Jane Park / The University of Sydney deals with the issue of Asian masculinity in predominately white cultures, specifically Australia. The article references the film “Romper Stomper”, a movie about Australian skinheads. Up front, the movie deals with topics such as gangs, violence, and drugs. In the movie, the Asian male is represented as a subordinate figure to the Australian white man. This is shown through the Asian males inability to develop a non-taboo relationship with white women, and the struggle to even be noticed in a romantic sense by white women. Another way that the movie “Romper Stomper” shows the Asian male as subordinate to the whites is by making the Asian characters low-life drug dealers. This represents Asians as poor and dirty people. The ideology of the Asian male lacking masculinity can be seen in both Australia and The United States. The misconception that white people are the dominant race is common throughout western society.

In the article the racist view towards the Asian male is further developed. The Article separates the Asian male into two categories, The Asian tourist and the Asian immigrant. Racism heavily undermines each of these categories. For the tourist, it is Ok to travel, as long as you go back to your country. Because of the misconceptions of Asians, they are seen as an economic threat and a protagonist. This is the problem for the immigrant.

The Asian male is certainly seen as a less masculine figure in the media. Although it is a misconception, the ideology still holds within television culture. In real life the Asian male is not subordinate, but in media, the racist ideology is still present.

Although it is true that our world is getting more and more progressive in terms of racial equality, most media and business in general are still owned and managed by wealthy upper-class white males. This in turn affects the representations of race on television and film. It seems that the representation of Asians in Australian film is going through the same issues that African Americans have gone through in the media. The balance has not yet been found between over-stereotyping Asians and whitewashing them. In over-stereotyping them, they are emasculated and seem to be contained within this feminization as being unable to be taken seriously or making logical decisions. When they are whitewashed, we become colorblind because they act as any other white actor would act. These are both problems within the media, but are they necessary steps towards equal representation in the future?

This article brings up an interesting point about the silence from critics about the interracial aspect of the dating relationships in Australian movies like Japanese Story and Little Fish. Issues of interracial dating and marriages stretch across many cultures and are especially prevalent in the histories of the U.S. and Australia. In the U.S. interracial dating has long had a stigma as being deviant and was even made illegal in many states. White women who slept with black men were seen as having been sexually corrupted and white men who slept with black women were seen as being dirty and perverse. While I don’t know as much about interracial dating in Australia I am aware of cases in which the mixed offspring of aboriginal and white couples were sent to school to teach them white culture and domestic servant skills so they could move to white cities, enter marriages with whites, and eventually “breed out the black”. Given the long and checkered history societal perceptions of interracial dating, it makes sense that critics would be uncomfortable bringing it up while reviewing movies, but it is also that more important that they do so.

Jane, I really enjoyed reading this article and think you brought up a lot of good points including the representation of Asian males as feminine, soft spoken, and sexually inexperienced and inept. As an Asian American myself, I, too am saddened by the portrayal of Asian males in world cinema. “Asian men rarely appear as romantic partners for anyone, and especially white women, in Hollywood cinema due to still prevalent stereotypes of the feminized, desexualized or otherwise emasculated Asian male in the U.S.–stereotypes rooted in the history of Chinese male immigrants who were systematically ghettoized, forced to take feminized domestic jobs, and prevented from forming families thanks to anti-Asian exclusion laws”. I think it’s really important to bring up the history of Chinese immigrants as a source of this continuing stereotypical image of the Asian male. However, I’m curious to know if you would agree that a lot of this has to do with the global market and the ‘threat’ of Chinese prosperity rather than just outright racism. I think regardless of how ‘liberal or ‘open’ politicians appear to be, they are not a symbol of real change as long as they keep defending the privilege of wealthy, white males who control most government agencies and corporations.

Hi everyone, I’m sorry for the delay in responding to your great comments. Thanks so much! Please feel free to email me at jane.park@usyd.edu.au if you have any more suggestions as I’ll eventually work this into a longer piece and would love your input. Below are my responses to specific questions:

Olivier: I think your notion of contamination working as a part of national integration is really interesting – could you say a bit more? I’m not sure how well that metaphor works for the relationship between Tracy and Johnny. It’s significant he survives whereas the gay white father figure dies, but it’s so ambiguous what his role will be at the end of the film. Not to mention the fact that he is played by an Asian American actor…

Ariell: I think you’re right to point out that parallels exist between how people of Asian and African descent have become and are continuing to become more visible in popular media in the U.S — i.e. finding a balance between “whitewashing” and stereotyping. At the same time, there are differences in _how_ they’re normalized and exoticized, especially along lines of gender and sexuality (which I deal with elsewhere). As for necessary steps toward equal representation in the future — such a huge question! /and one that comes up all the time as I’m sure it does for most of my colleagues who work on race, ethnicity and media. I swerve toward answering that with a two-fold approach: more representation behind and in front of the camera and careful, nuanced critiques that try to go beyond the postive/negative representation approach — since in the end, what we’re hopefully aiming for are multiple and complex representations of all groups on screen and in the academy … or at least that’s what I tell my students :)