Are You Smarter Than a Cuban Customs Official?: Reassessing Cuba’s Commercial Television Influence in Latin America

Yeidy M. Rivero / Indiana University – Bloomington

“Comrade, I completely understand why you want to do research on Cuban television because we had one of the most developed television systems in Latin America. Unfortunately, you have the wrong visa.”

I am paraphrasing–and translating into English–my reception at Havana’s José Martí International Airport last year. I begin with this anecdote not to point out the difficulties of getting into the country, but instead to highlight that even a Cuban customs official, a daughter of the Revolution, is aware of the primacy of Cuba in the region’s television past. I emphasize the word “even” to draw attention to the knowledge gap between this customs official and US scholars. That is, if one reads the English-language literature on Latin American TV, one would have little awareness of Cuba’s once prominent position in the region’s mediascape.

To be sure, in the last decade numerous articles have focused on Latin American and US Spanish language television/media, most of them dealing with contemporary television exportations, powerful media conglomerates, and the popularity of telenovelas around the world. Yet at the same time that multi-national corporations are gobbling up and transforming the region’s television systems, the narrative about Latin American television has been responding to the market and to the corporations that control that market. As a result, the television systems and countries that are not current global business players are left out of the narrative. This scholarly trend not only presents a fragmented depiction of the region’s television/media present but it also misrepresents the Latin American television/media past. Today’s scholarly dialogues on the geo linguistic TV/media revolve primarily around Mexico, Brazil, and Miami, with much of that discussion relating to telenovelas.

Thus, my introduction to Cuba’s commercial television did not come from the literature. It emerged instead in talking to media professionals. In my conversations with Cuban and Puerto Rican actors, scriptwriters, directors, and technical staff who worked in Puerto Rico’s media before and after the Cuban Revolution, I began to learn about Cuba’s role in the development of television in different parts of Latin America. Through subsequent archival research and conversations with scholars from Venezuela, Colombia, and Argentina, I was gradually able to piece together the details of the “Cuban influence” in the region. Cuba’s impact related not only to big shot media moguls such as Diego Cisneros (founder of Venezuela’s network Venevision) and Goar Mestre (who, in conjunction with CBS, launched Channel 13 in Argentina), but also to relatively unknown figures who were instrumental in various aspects of television and advertising in Argentina, Peru, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and the US Spanish-language media market.

The beginnings of the Cuban media influence across Latin America and the Spanish Caribbean can be traced back to the radio era and, as expected, the US was a key player in Cuba’s regional media role. However, other aspects went beyond the long-established US neo-colonial presence in Cuba. During the 1940s, Cuba enjoyed an economic, intellectual, and cultural effervescence. The Cuban economy expanded during and after World War II, and although this economic prosperity did not benefit equally all sectors of the population, by 1950 Cuba ranked as one of the most economically developed countries in Latin America. In the cultural terrain, a new group of literary figures emerged, the number of formally trained musicians increased, and popular musical groups flourished locally and internationally. Furthermore, in the early 1940s, theatre aficionados had the opportunity to obtain a formal education at the Drama Conservatory and at the University of Havana. Because of newly established educational venues and a variety of professional opportunities in radio, theatre, and night clubs, the city of Havana was the center of popular culture on the island. In the 1940s, to use Michael Curtin’s concept, Havana became a media capital.

In addition to the aforementioned circumstances, particular industrial and commercial factors–directly and indirectly related to the post 1898 US political and economic interventions in Cuba–came together to position Havana as a broadcasting hub. The early investments of the International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation, the Cuban media professionals’ training in and mastership of US advertising techniques, and the appropriation of US radio production practices facilitated the maturity of Cuba’s broadcasting industries. All of these local and US-shaping vectors were instrumental in Havana’s regional impact during the 1940s and 1950s.

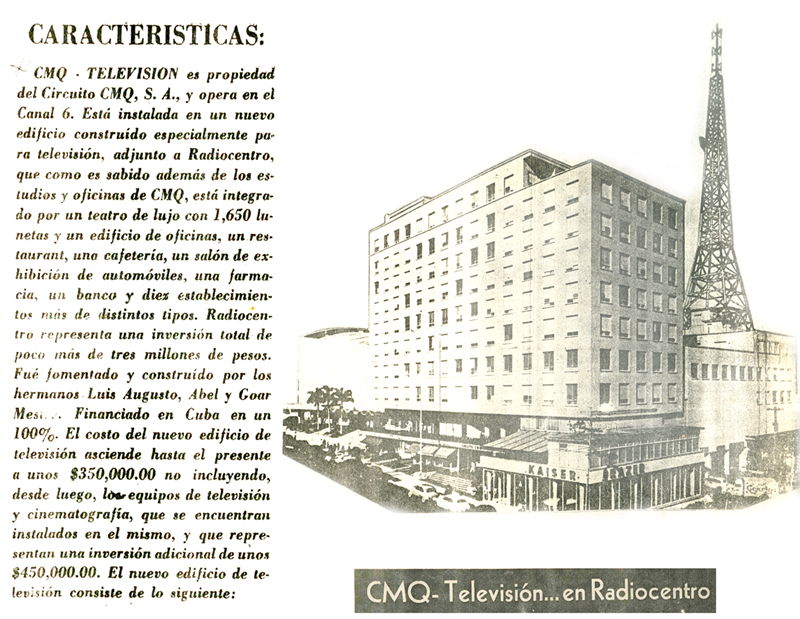

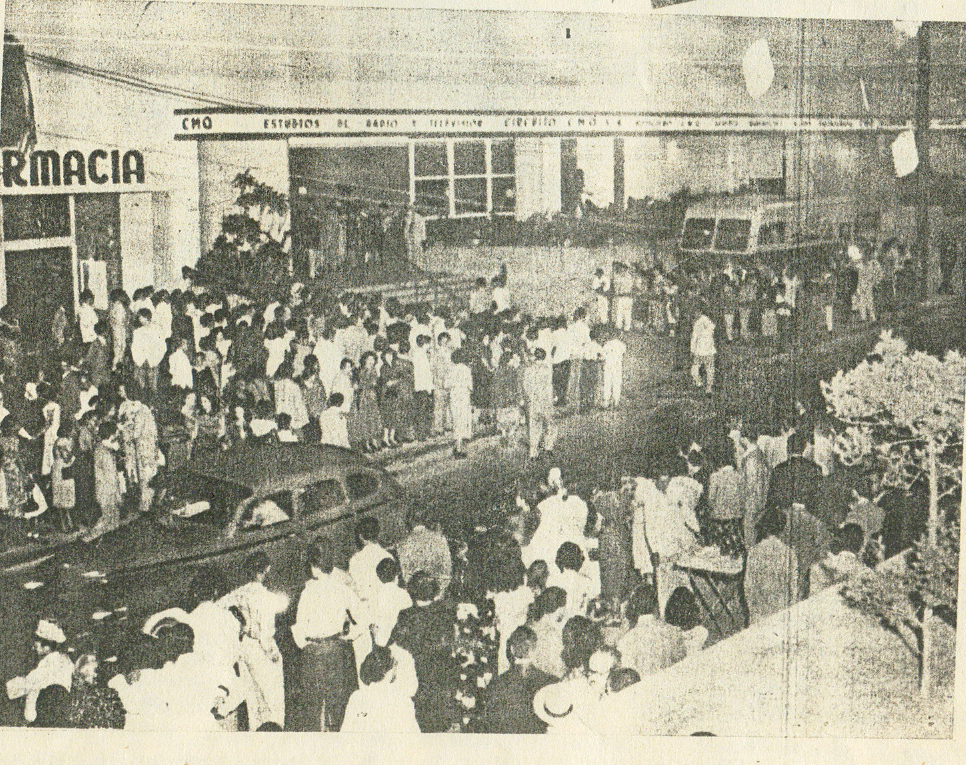

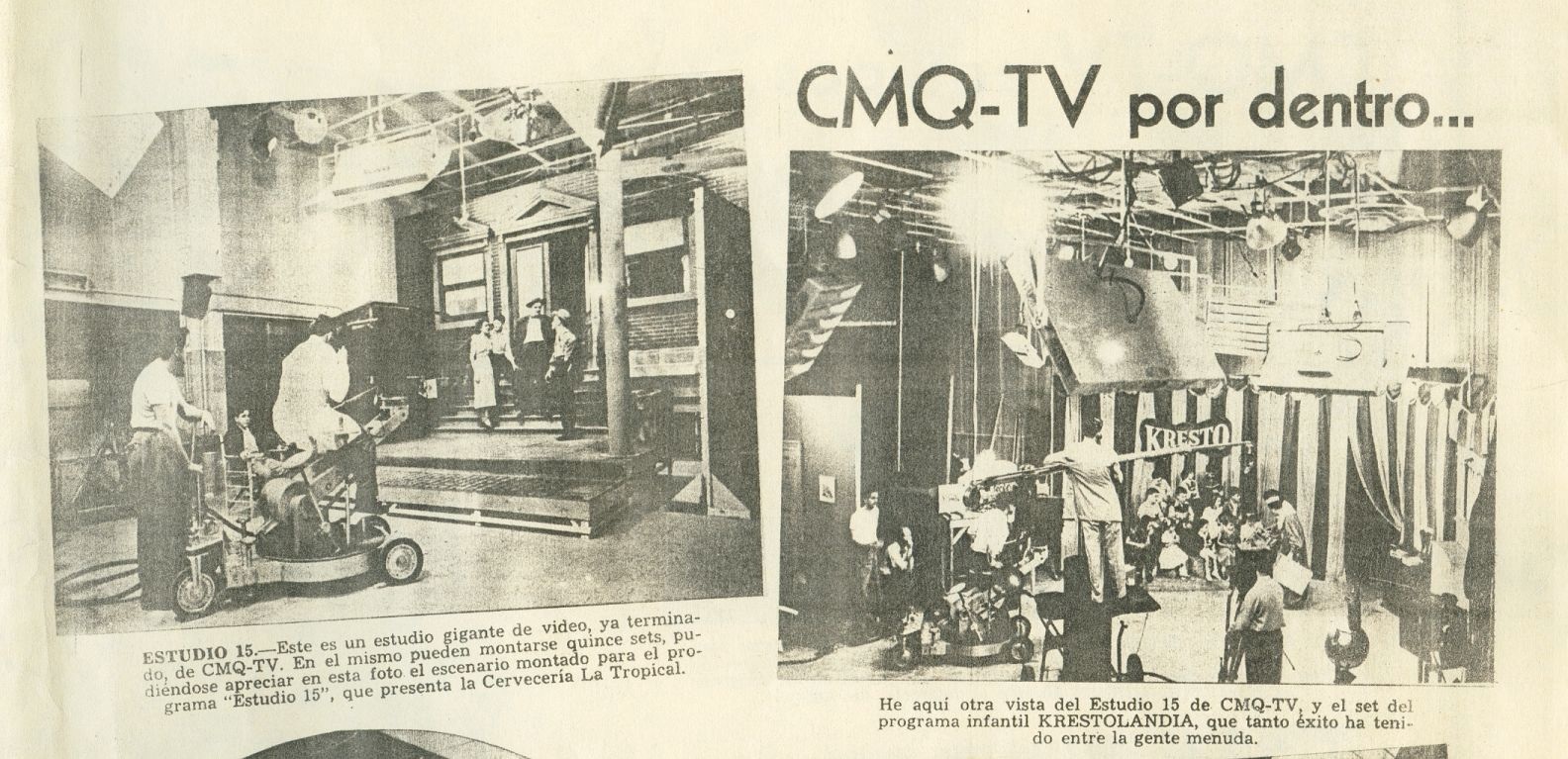

The Havana broadcasting influence in Latin America first came into place through the sale of scripts and soon after, in the transferring of advertisers, radio directors, and scriptwriters. Much of this exportation of scripts and people was fueled by US corporate investments in the region. Nonetheless, not all Havana-Latin American connections were a result of US economic interests. In some instances, Cuban advertisers foresaw the emergence of opportunities and expanded their business to other countries. In other instances, Latin American advertising agency owners traveled to Cuba in search of advertising and radio professionals. This movement of Cuban media professionals across the region continued into the 1950s television era. The Cuban television industry grew exponentially in its first three years (1950-1953), and, as a result, its television professionals were able to develop their technical and production skills. Cuban expertise in television, together with the nation-state’s troubling economy after 1954 and a progressively unstable political climate, led to an exodus of television and advertising professionals who migrated to other media centers throughout Latin America.

Three primary aspects facilitated the relocation of Cubans: first, the emergence of television in numerous countries throughout the region; second, the lack of trained personnel in the countries that set up this complex system; and third, Cubans’ vast experience in multiple aspects of television production. Contrary to the post 1959 migrations, the move of Cuban technical staff, television and advertising executives, and talent was in many cases transitory. However, what is important about these sometimes permanent, other times temporary relocations is that they solidified the Cuban connections in Latin America and served as important links for the post 1959 mass departures.

Bogotá, Caracas, and San Juan were the primary cities Cuban media personnel selected as their new job sites, yet several Cubans also looked for jobs in the Dominican Republic and in Mexico. In the case of Colombia, the Cuban influence was related to the technical aspects of television. In Venezuela and Puerto Rico the Cuban connections encompassed the technical, commercial, and cultural aspects of television.

The pre-revolutionary connections and dispersions of the 1940s radio era and the 1950s television era facilitated the incorporation of Cubans into the Latin American and US Spanish-language media industries after the Cuban Revolution. Certainly, not all Cuban executives, technical staff, and creative personnel went into exile. The television professionals who stayed on the island became key members in the State-controlled broadcasting system and in the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry. Additionally, the highly experienced advertising professionals who remained in Cuba played a fundamental role in crafting propaganda campaigns to form a new socialist state and citizenry. Nonetheless, those who left became important figures in the development of broadcasting and advertising corporations in Buenos Aires, Caracas, Lima, Miami, New York City, Rio de Janeiro, and San Juan. And yes, these Cuban exiles even influenced the telenovelas produced in Mexico, Brazil, and Miami.

Cubarte

Since the mid 1990s, Cuban-based intellectuals have embraced a more flexible interpretation of pre-revolutionary Cuban history, culture, and society. Since early 2000, the Havana-based on-line magazine Cubarte has included a column covering pre-revolution radio and television. Caballero!!! (as the Cubans say), when are we going to catch up to Cuban customs officials?

Image Credits:

1. Private Image

2. Private Image

3. Private Image

4. Cubarte

Please feel free to comment.

Thank you to this useful and valuable information to connect desktop with wireless Bluetooth device so that users can manage to audio video sounds with superb quality.I am also learn through this all the steps to activate this feature.