Rage Against the Machine: Does The Sarah Connor Chronicles Have a Future?

Heather Hendershot / Queens College/CUNY Graduate Center

When James Cameron’s Terminator—a scrappy, medium budget sci-fi-action movie—appeared in 1984, its novelties were twofold: it ended with a time travel paradox handcrafted for sci-fi nerds, and it starred Arnold Schwarzenegger as a killer robot from the future. The future Governator was hotly pursuing a movie career after mildly successful turns in Conan: The Barbarian, Pumping Iron, and (a cameo, in his underpants) The Long Goodbye. By the end of The Terminator, Sarah Connor has crushed the Terminator, been impregnated with John Connor (the very warrior from the future who sent his own father back in time to impregnate his mother), and gone off into the desert to prepare for the apocalypse, when the Cyberdyne System’s Skynet computer defense system will annihilate most of the human race.

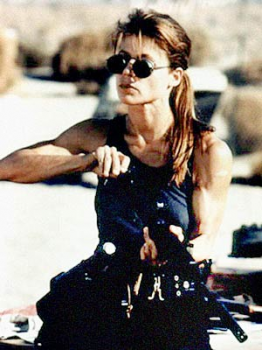

Terminator 2: Judgment Day picks up in 1991, with Sarah in a mental institution. Her apparently loony predictions about robots from the future are, of course, correct, but that doesn’t mean she’s not crazy. The seeming inevitability of global apocalypse has driven her off her nut. Still, she’s been working out pretty hard, and if she’s not mentally equipped to fight for the future of the human race, she’s got the biceps for it. Schwarzenegger appears again, this time reprogrammed as a good guy determined to fight off a liquid metal bad guy out to kill John Connor, now a wisecracking juvenile delinquent.

One quickly has the feeling of watching two movies unfold. First, a tense psychological drama about Sarah, who wonders if there is “no fate,” if the future is open to change, and how one human can possibly make a difference. Second, a special effects movie, with Pepsi product placement, cool catch phrases, and a primary mission more pressing than saving the world from apocalypse: making Arnold into a family values action hero. As John bonds with the terminator, Sarah observes: “Of all the would-be fathers who came and went over the years, this thing, this machine, was the only one who measured up.” The movie ends on a note of hope. Cyberdyne’s headquarters have been destroyed; maybe the apocalypse won’t come.

By the time Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines appeared in 2003, Sarah had died of leukemia. The special effects thrust that dominated T2 survived, and the other submerged film, the psychological drama, was kaput, notwithstanding a few token gestures. Arnold was back, along with a new evil, chesty terminator. Ticket sales were solid, although almost everyone seemed to find the film a terrific bore. But it was unstoppable, programmed to promote video games and the next sequel, Terminator Salvation, which will be released this summer. It’s sure to be a blockbuster, but no serious science fiction lover would expect anything interesting from the franchise at this point.

Not in movie theatres, anyway. On TV, that embedded film about crazy Sarah Connor has been rebooted. Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles is now in the middle of its second season on Fox, and it is a show with big ambitions, if little budget. The premise is that another reprogrammed terminator has been sent from the future to make sure John Connor survives to lead the human resistance against the machines after Judgment Day. This terminator—named Cameron, after the franchise’s creator—is an attractive teenage girl. Or she looks like one, at least. Sarah is still alive, but Cameron informs her that she will die of cancer in a few years. The series takes place after the events of T2 and draws upon plot points from that film whenever it’s handy, but the driving force of the show exists wholly apart from the rest of the franchise. The program’s central concern is to ask, faced with inevitable failure—because of fate, the apocalypse, or simply the death that awaits us all—what does it mean to be human? What are our obligations? How do we live, knowing that it’s all going to end?

It is Cameron who best helps sort out these issues. Cameron learns to imitate humans, not because she yearns to be human but because it makes her more effective in her mission. If Schwarzenegger had “Hasta la vista, baby!” Cameron’s tagline is simply factual: “I don’t sleep.” This explains a lot. It’s not unusual for her to appear in the morning with a badly needed piece of information or machinery. In early episodes, this is simply a handy way to push the plot forward, but “Self Made Man” reveals what Cameron actually does while everyone else is asleep. Has she been cooking up plastique, hacking into the FBI’s computer systems, or plotting assassinations?

Much cooler: she spends her nights in the library listening to radio broadcasts preserved on old LPs, speed reading microfiche, and projecting silver nitrate newsreels. Google is out of the question: Cameron is only interested in analogue sources of information. She arrives with a bag of donuts, and the library’s night clerk lets her in and acts as research assistant. Having only simulated emotions (her smile could crack a mirror), Cameron’s manner is a bit off putting to the young man, but he gathers that she’s just got “issues.” (Indeed, a psychologist has already declared that Cameron suffers from “borderline Asperger’s.”) The night clerk thinks his cancer is in remission, but Cameron discerns he is sick again and tells him as much. She thinks she’s helping, but her manner is brusque, and he rejects her. He’s gone the next day, and the new clerk is dubious when Cameron knocks at the back door, but empty gestures of friendship and a bag of donuts gain her admittance, and she’s back in the stacks in a flash. “Self Made Man” does have a puzzle to solve—the reason for Cameron’s research—and it ends with a quick fight scene to wrap everything up. But the heart of this episode lies in Cameron’s lack of heart, in watching her get what she wants by feigning friendship, in seeing her gauge what works and what doesn’t in conversation. She’s got no instincts for how human interaction works, so she has to simply memorize the mechanics. The Asperger’s diagnosis was not far off the mark.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCZWqx_AG58[/youtube]

The common science fiction trope that a robot’s dearest wish would be to become human is reassuring. It confirms that being human is better than being a machine. In the first Terminator, there was no question of humanizing the robot, but Sarah concludes T2 with a hopeful voice-over: “If a machine, a terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can too.” This carries over to Schwarzenegger in T3. Cameron may be the same model as the Schwarzenegger terminator, but she’s no Pinocchio—or Tin Man, as Sarah sometimes calls her. Instructed not to kill humans who might help bring about Judgment Day, she asks “why not?” She refuses to “learn the value of human life,” not because she is willful, but because it’s not in her programming. Sarah and John want to stop the apocalypse but are unwilling to kill people who might be innocent. John and Sarah cling to human compassion, and this makes them good, but probably less well equipped than Cameron to save the world. Their compatriot Derek Reese, on the other hand, a human warrior from the future, has no compunction about murdering anyone whose actions might lead to Judgment Day. Derek hates Cameron and mistrusts machines, yet he lies and kills as much as Cameron. She’s a killing machine, but it is he who is the unethical one, as he has free will.

This is what the show is about. But what actually happens? A lot, and also not much. Every week our would-be heroes do something that might prevent the apocalypse, but they can never be sure they have really accomplished anything. In Ray Bradbury’s famous “A Sound of Thunder” (1952), a time traveler is cautioned that even the smallest change in the past may influence the future; the traveler accidentally crushes a butterfly beneath his boot, and he returns to find the present changed for the worse. That time travelers should not risk changing history has become an axiom of science fiction, but Sarah Connor protagonists desperately stomp at every butterfly in sight, struggling to change things—the future can’t possibly be any worse, they reason. At one point, a visitor from the future has different memories from Derek Reese, who arrived in the show’s present at an earlier point in time. Derek speculates that all of the butterfly stomping must have changed something; the later visitor remembers different things because she is from a different future. But it’s still an apocalyptic future.

Sarah Connor is depressing, lacking the liberal optimism and faith in human evolution that fuels much sci-fi, especially the Star Trek franchise. Season One, for example, ends with a terminator annihilating an entire FBI team, as Johnny Cash’s “When the Man Comes Around” plays, emphasizing the inevitability of the Grim Reaper. (In another episode we learn that John Connor loves The Smiths—no upbeat pop tunes in this universe!) In tone, the series evokes Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, a series rejected by many Trek fans for its deep interest in religion and politics, its post-apocalyptic tone, and its picture of a fractured, non-logical universe full of traumatized POWs, guerilla warriors, and drug-addicted military conscripts. Sarah Connor, to put it in terms that will be appreciated by DS9 fans, is more likely to draw Odo lovers than Data lovers.

It’s difficult to reconcile the action movie side of the Terminator franchise with this cheap, clever little TV series spin-off. Maybe once a franchise gets big enough all of its parts don’t have to cohere. Interviewed by Robert Trate at the 2008 San Diego Comic Con, one of the show’s executive producers, Josh Friedman, said he had been in touch with Salvation director McG, but that he wasn’t really concerned about the show’s relationship to the movie: “McG and I decided that I would do my thing and he would do his. It’s a $200 million movie. Their trailers cost as much as our shows do. What TV does best is character. At the end of the day that is what we do best.” Friedman added, “The movie franchise post T3 was perceived as not that healthy. Maybe they need us as much as we need them.” This might sound like wishful thinking, as Sarah Connor simply isn’t going to survive if its ratings don’t improve, but it’s an interesting notion. Sarah Connor supplies the franchise a bit of intellectual credibility, and its character driven nature will draw a subset of viewers less interested in the action side of the franchise.

Ultimately, it’s hard to predict Sarah Connor’s fate. On the one hand, termination seems inevitable. It has previously aired on Monday nights, but on February 13 it returned on Fridays as a lead-in to Joss Whedon’s Dollhouse. Friday night scheduling is widely considered to be the kiss of death. On the other hand, Whedon’s cult following should bring new viewers to Sarah Connor. Indeed, both shows are sci-fi dramas about what it means to be human. Anyway, how much longer can scheduling make or break a show, as fewer and fewer Americans watch shows live, or even on their TVs? Last summer Whedon had a hit with Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, which never actually aired on TV and could be watched any time at all. Whedon fans will TiVo Dollhouse and watch it whenever the hell they want, and why not check out the show’s lead-in too? Maybe Sarah Connor will die in the Friday night dead zone, but maybe not. I like to think that Dollhouse will offer its hand to the show and say, “Come with me if you want to live.”

Image Credits:

1. Promotional image for Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles

2. Linda Hamilton as Sarah Connor in T2

3. Cameron, not quite human

Please feel free to comment.

Nice essay. Note to self: forward to all grad students working on franchises.

Yes, the show has been moved to Friday in order to die after its utility as a promotional vehicle for the T4 film has passed. This show has consistently suffered from some of the worst scripting and character treatment in recent Television, though the first episode of Dollhouse was remarkably horrible too.