Goodbye Rabbit Ears: Thoughts About the Digital TV Transition

Lisa Parks / UC Santa Barbara

The shift to digital television is scheduled to occur on February 18, 2009 in the US. This historic shift, often compared to the inauguration of color TV, has been referred to as “The Digital TV Transition” by the FCC and has been widely publicized for the past several months. As I write this column, the FCC website provides the countdown to the digital transition as 74 days, 13 hours, 4 minutes, 49 seconds. This is an important moment for television scholars: the future of television is in the public spotlight, and there are opportunities to draw attention to various TV-related issues ranging from media conglomeration to e-waste from writer’s salaries to spectrum allocation, particularly since the issue of media reform got lost in the 2008 elections. Further, following on important work by William Boddy, John Caldwell, and Lynn Spigel among others, we might also consider how this historic moment suggests new directions for TV research, whether on the relationship between the FCC and citizens/viewers, local and regional television, or the visualization of television technologies.

Though regulators and manufacturers have already made many of the key decisions about the future of television, technological negotiations remain for many consumer/citizens. There are an estimated 19 million US households still using analog television sets. (In technology studies we often hear of the “early adopters” and we might call this group the “diehard users.”) Owners of analog sets will have to decide how and whether they want to continue to receive a television signal and can either purchase a digital converter box or a television set with a digital tuner, or can subscribe to cable or satellite television. The federal government has subsidized the transition and the National Telecommunication and Information Administration is administering a $1.5 billion coupon program to support those who want to retrofit their analog receivers with converter boxes.

Despite TV scholars’ recent focus on cable, satellite, interactive and web-based TV, it is important to recognize that a significant chunk of the US TV audience—roughly 15%—has continued to receive “free” over the air signals for decades. What if the moment of the digital transition led to scholarly investigations of the analog diehards rather than the technophiles that raced to join the alleged digital TV “revolution”? Given the fixation on novelty in our techno-culture and often in our field, we have much to learn from consumers who, whether by default or by choice, continue to use machines simply because they still work. It’s too easy to equate the use of old machines with poverty or reticence.

Many assume that analog TV viewers are elderly folks who grew up with rabbit ears, and indeed some of them are. Yet a glance at the FCC digital transition website reminds us just how diverse the US TV audience is. Information about the transition is provided in the following languages: Amharic, Arabic, Bosnian, Cambodian, Chinese, Creole, French, Hmong, Japanese, Korean, Kurdish, Laotian, Navajo, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Somali, Spanish, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Yupik. That this array of languages appears suggests that ethnic communities might be particularly impacted by the transition. Some of these communities have historically received local over the air programming in their own languages. Whatever the case, there have always been multiple “televisions”—whether the standards are analog or digital—shaped in part by the various communities that arrange and use the technology. Clearly, we need more research like Hamid Naficy’s study The Making of Exile Cultures: Iranian TV in Los Angeles (U of Minnesota, 1993) or Eric Michaels’ Bad Aboriginal Art (U of Minnesota, 1994). We need to understand what television technology means to different communities in urban and rural areas in the US and beyond.

Over the past several months we’ve seen an armada of public service announcements heralding the transition. National and local organizations have gone to great lengths to communicate with viewers about it. One PSA that frequently airs on CNN features a sixty-something man strolling through a barren landscape, and, as the sun sets behind him, he announces the end of analog and birth of digital TV. Another stars FCC Chairman Kevin Martin with a direct address to TV viewers in which he bluntly states, “Your TV needs to be ready so you can keep watching.” Yet another presents a popcorn-munching family huddled around a suspense show that disappointingly turns into static. Finally, a parody reveals a sweet elderly woman trying to set up her converter box. After wrestling with tangled cables she asks, “Will all of this make Jack Benny come back?” She then snips a cable with her scissors and sticks her remote control in the microwave in a desperate effort to capture the digital signal.1 This broad collection of PSAs, of which I’ve mentioned a tiny sliver, provides an important site for scholarly engagement because it registers the various ways in which the public has been encouraged to understand and negotiate the transition.

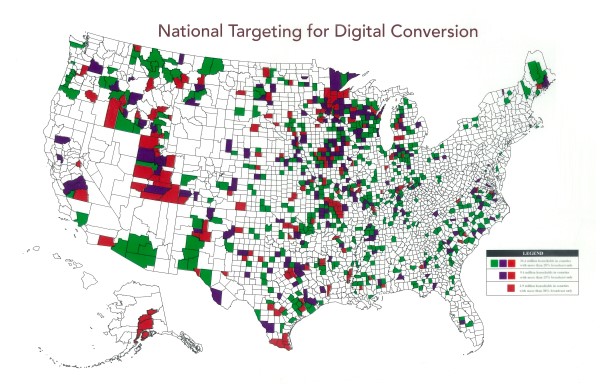

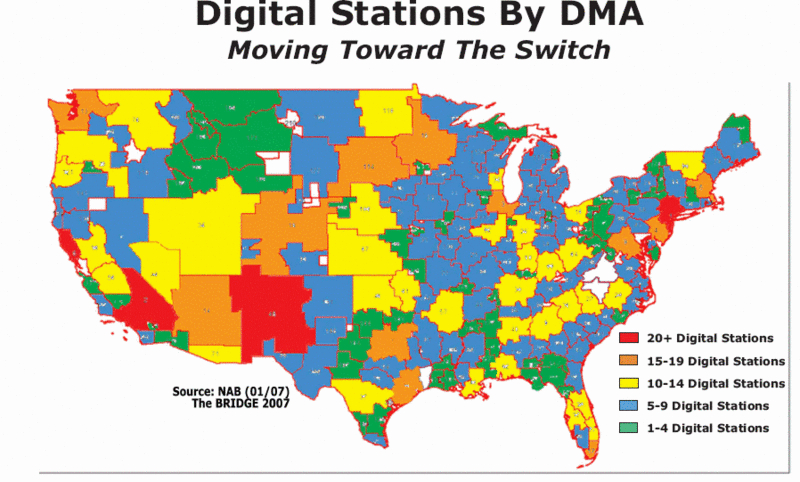

As someone long interested in the way technical knowledge about television circulates, I find these attempts to visualize or manifest the analog to digital shift quite fascinating. Not only PSAs, but also “how to” manuals, flow diagrams and maps have been used to guide citizen/consumers through the transition. One color-coded map puts these issues into cartographic perspective as it reveals areas in the US with a high density of analog TV users. A 2007 National Association of Broadcasters map illustrates the relative density of digital television stations in the US, showing the areas best prepared for the transition. Such visualizations are extremely useful documents for TV scholars and educators because they can help us comprehend and convey television’s spatial and territorializing properties. Further, each PSA or map is an attempt to translate largely imperceptible technical processes (which we are socialized to remain naive about) into intelligible forms that can be interpreted and discussed.

Thus we might think of the digital transition as a meta-moment in television’s history in that we are confronted with various manifestations of television itself. Rarely are citizens/viewers encouraged to think so carefully about how they get their signals and how their receiver works—to think so specifically about an object that is at once so familiar and so strange. This can be a useful moment, then, in that there is an increase in the circulation of technical knowledge about television in the public sphere. And the analog diehards, in particular, are being addressed, lest they be “left behind” or remain beyond what Mark Andrejevic has called the “digital enclosure.”2 Still, several questions linger, even as new knowledge about television circulates. After the transition will citizens know not only what digital TV is, but what the FCC is and who its Chair and Commissioners are? Will they care about where their trashed analog TV sets and antennae end up? Will they insist that community television stations not die along with analog TV? And what will become of the white space—that part of the spectrum left open in the wake of analog TV’s termination? Finally, what does this mean for the future of television scholarship? It is my hope that we will continue our research backward and forward at once, and keep the enticing shimmer of the new – whether we call it the digital or something else – in perspective so that we can continue to explore the multifarious ways in which people in the US and beyond have (re)arranged, tinkered with, hybrized and defined television technologies in the past and will continue to do so in the future whatever its standard.

Image Credits:

1. Rabbit Ears

2. National Targeting for Digital Conversion

3. Elderly Woman vs. Converter Box

4. Digital Stations By DMA

Please feel free to comment.

Lisa, thanks for an interesting column. What I find to be the most interesting part of the conversion is when the information is displayed during different programs. The most glaring time when I see the networks reminding viewers of the change is during The CW’s Gossip Girl. It’s fascinating to think about the reasons for the scrolling text during such a popular teen/20something series.

Great column. Piggybacking on Tiff’s point, I think that twenty-somethings might, ironically, be the most clueless about the transition. ESPECIALLY graduate students (outside of departments like ours, of course) whose poverty (or lack of time) demands bunny ears, who watch TV only during sporting events (where are the infomercials then?) or near-exclusively for DVD use. These aren’t old people, dumb people, or even late adopters (many of them have very sophisticated technology outside of the TV).

What is it about TV reception that makes it seem unchangeable and constant? That makes smart, connected people ignore change? Is this akin to, say, the post office threatening a massive paradigm shift in the way it delivers mail, but no one gives a crap because they rely on it only for bills and cards from grandma?

I like this article a lot, but I have two concerns.

1. I disagree with your term “diehards.” I think that term has some implications that you don’t mean. Do you really think that the people who still use rabbit ears do so because they have beliefs that will not be swayed? Or isn’t it more out of necessity, ignorance, or laziness?

2. You write, “Many assume that analog TV viewers are elderly folks who grew up with rabbit ears, and indeed some of them are.” and then try to disprove this assumption. Your single argument on this front is the availability of many languages on the FCC website. I don’t buy it. I still think it is just old people and those without the economic means to afford cable. I am, however, willing to be proven wrong, but I need more than translations. There are poor and old ethnic folks, too. I think Tiff may have been on the right track in bringing in the fact that it is advertised on Gossip Girl. But she also expresses an accurate feeling that it is being broadcast to an audience that probably isn’t affected.

Appropriately, the one community that will not be affected by the transition are those engaged in EVP (electronic voice phenomena) research. Some in this group still videotape “empty” broadcast channels searching for ghost images and voices. TV may go digital, but ghosts remain profoundly analog!

So, for those who choose not to subscribe to cable or satellite and get a converter box for their analog TV instead, how will those people get a signal if rabbit ears are obsolete? I don’t understand. Please clarify.

That’s what the converter box is for, to provide a signal for people without a cable or satellite subscription.