Climate Change Virus Targets Poland! Copenhagen and China next!

Chris Russill / University of Minnesota

Meet the most important meme in the world. 350. It is an “absolutely inert” figure, one that “means nothing, comes with no associations.”1 350. Do what you can to “tattoo that number into every human brain.”2 350. “We think that if we can take that meme – 350 – and spread it everywhere, it will almost subconsciously set the bar for these negotiations much higher than it currently stands.”3 The reference is to the annual United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) Conference of Parties where global climate change discussions are held each year. Poland hosts this year, Copenhagen next year. Climate change activist, Bill McKibben’s plan is simple. If “350” is transmitted via a global media campaign, these international negotiations “will be pulled as if by a kind of rough and opaque magic toward that goal.”4 350. “It will set the climate for talking about climate.”5

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5kg1oOq9tY[/youtube]

Infected yet? Seriously though, McKibben’s pleas on behalf of environmental change are often passionate, courageous, and illuminating, so his decision to abandon words and to seek global media influence though “350” is worth some reflection. McKibben helped launch the admirable “Step It Up” campaign in the U.S., which called for an 80% reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2050. As an initial step toward addressing global climate change, it was broadly inclusive, a qualified success, and a good example of building community relationships in the context of national problems.

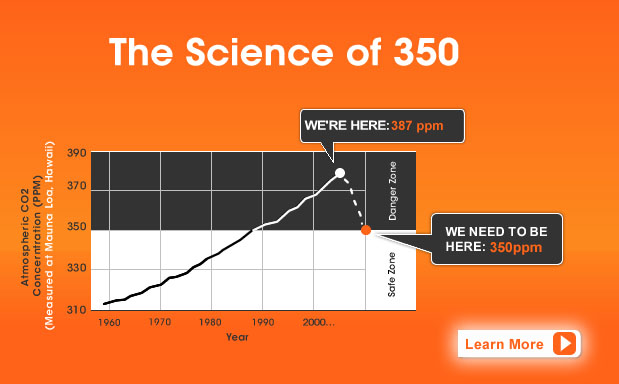

Now, McKibben is going global with a media campaign he considers a “Hail Mary Pass.”6 Polysemous contagion is encouraged, but there is a story to 350. James Hansen, the NASA climate scientist bucking Bush Administration policy, has stated that if the atmosphere exceeds 350 parts per million of CO2 for too long then the planet will start passing irreversible tipping points. This is bad news because CO2 levels have been above 350 since the 1990s. Over the last four years, Hansen has raised the alarm regarding dangerous climate change and he has tried a number of metaphors: “loaded dice,” “time bomb,” “slippery slope to climate hell,” and now, in the warning McKibben takes as definitive, “tipping points.” You can read one of Hansen’s warnings.

How to take this warning global? As media and communication scholars, we should have something to say and do in this regard. Leaving aside questions about whether to set the CO2 threshold at 350, I’m plagued by concerns about how these efforts conceive global media influence. McKibben has a web site in 10 languages and photogenic, college-aged activists in still more countries engaged in a strange, cross-cultural, cognitive tattooing campaign designed around a number. Hansen writes letter after letter, delivers lecture after lecture, pleading publicly for recognition of tipping point danger to the leaders of states, nations, and anyone else that will listen. What is remarkable from a communication perspective is that both McKibben and Hansen rest their hopes on strategies derived from a peculiar cultural trend. They appear to have bet the future of the planet on the assumption that media transmission works something like viral infection.

The idea that influence works like influenza is a neat idea. But should it guide our global interactions in crisis situations? What does it mean to place one’s faith in an oddly conceived meme, or to place hopes for social transformation in the theory of tipping points? Richard Dawkins coined the phrase “meme,” as a meme itself, a shortened catch phrase derived from the Greek, “mimeme,” which suggests imitation.7 However, Douglas Rushkoff is the more likely source of McKibben’s inspiration. In Media Virus, Rushkoff proposed that communication campaigners implant memes within a media virus to infiltrate the way we perceive reality.8 The mixing of low-cost and “provocatively interactive” media with non-threatening messages was intended to penetrate and recode our conceptual frameworks while being both catchy and confusing (and difficult to explain!). When McKibben says 350 is without association, he probably means it. As Rushkoff once said, “deployment was the message” and his interviews with a range of virally inspired communicators made clear that the dissemination of an “it can be done” ethos was a primary goal.9

I doubt many climate scientists subscribe to these views. But some have adopted the tipping point concept made famous by Malcolm Gladwell. (For an animated warning inspired by tipping point views, see this video.) They often use the term carefully. On some occasions, however, the use of tipping points is applied to human activity and an account of the role of communication in shifting social behavior is operative. This occurs in surprising places. The editors of Nature, for example, claim that tipping points are “far more pertinent to the climate crisis in the social sphere than in the physical world.”10 Also, when James Hansen gave testimony to the State of Iowa regarding the consequences of coal-fired energy, he described tipping points in the climate, ecosystems, and human behavior. When asked why Iowa should restrict coal burning when China continues to burn coal unabated, Hansen offered an answer made famous by Gladwell. He claimed an Iowa decision against coal burning could be a “tipping point,” a message heard beyond the state that might chart a new societal direction. This is not an argument based on fairness, justice, or future competitive advantage (which, to be fair, Hansen has articulated before). It is one dependent on assumptions about communication. (You can read Hansen’s testimony here [see pp. 4-5]).

This is a new and exciting trend in climate change discourse, but I think these kinds of answers need greater consideration. In many instances of climate change policy, the idea of societal change through tipping points is advocated without consideration of alternative perspectives. On what grounds should the State of Iowa, or diplomats in Poland, or industrialists in China, or anyone else, accept an answer premised on tipping point explanations of social change? I also think that if Hansen’s tipping point answer is found wanting then media and communication scholars bear some responsibility for this situation. Too many of us have sat this one out for too long.

Let me start by raising two specific concerns before inviting your comments. First, are environmental advocates undercutting themselves with this kind of explanation? For instance, when Van Jones’ book, The Green Collar Economy, landed at #12 on the New York Times best seller list, one popular explanation was – you guessed it – viral marketing. What does this explanation tell us? What implications does it hold for addressing climate change or issues of environmental injustice? Van Jones’ book charts a path for bringing a much wider array of people into environmental concerns. Why explain it in terms of viral marketing? Why not use “networking” or more traditional “social activist” explanations? What is gained? What is lost? In Gladwell’s theory, success is explained by finding exceptional people (connectors, mavens, and salespeople) to carry infectious messages. Should this be the goal of environmental communication?

Second, what does it mean to appeal to people in Poland or Copenhagen or China as hosts of viral infection? The beauty of McKibben’s “350” is its proposed meaningless and hope for interpretive proliferation—it is the precise opposite of today’s fascination with “message discipline.” Still, I wonder about this as a model of intercultural engagement. Don’t forget that Donald Rumsfeld thought the tipping point perspective was an effective way of engaging other cultures.

So I wonder what media scholars and students make of this trend and I’m interested in what we should say to climate change activists letting it all ride on these ideas.11 Viral accounts promise not only a different way of looking at the world, but one in which you suddenly seem to have special powers, or greater agency at any rate. One begins to look at communication in a new way and the “it can be done” ethos is very different from the staid entrepreneurial solutions so frequently advocated.12 Are these advocates right or misguided? If communication does work in this fashion, is the release of media viruses in foreign countries something to be considered more deeply? If they are wrong, how should we communicate climate change differently?

Image Credits:

1. 350 Campaign

2. Atmospheric CO2 Concentration

Please feel free to comment.

- Bill McKibben, “When words fail: Climate change activists have chosen a magic number,” Orion, July/August, (2008): 19 [↩]

- McKibben, “When words fail,” 19. [↩]

- Bill McKibben, “350,” Grist, April 18, (2008), http://gristmill.grist.org/story/2008/4/17/113351/369 (accessed October 20 2008). [↩]

- McKibben, “When words fail,” 19. [↩]

- McKibben, “When words fail,” 19. [↩]

- Bill McKibben, “Earth at 350,” The Nation, May, (2008), paragraph, 20, http://www.thenation.com/doc/20080526/mckibben (accessed October 20 2008). [↩]

- Richard Dawkins, The selfish gene (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), 192. [↩]

- Douglas Rushkoff, Media virus. (New York: Random House, 1994), 10. [↩]

- See Christine Harold’s Our Space (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007) for an illuminating account of this perspective. [↩]

- Editor’s summary. Nature 441, 785. [↩]

- There is a growing academic literature that deserves mention. Lawrence Grossberg, Paula Treichler, John Erni, Richard Doyle, Christine Harold, Gordon Coonfield, Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker, have done interesting work. [↩]

- This viral trend is not confined to climate change issues alone. It is just one example of a non-infectious, non-contagious phenomenon that is now treated in terms of an disease epidemic view of crisis. Yet climate change is of enough importance that [↩]

A thought-provoking piece. An element I find interesting with the “350 animation” is the message it conveys without the use of words. I think a further complication of these questions of concern is how best to communicate on a global scale with the so-called language barrier(s).