Requiem for a “King”: Something about Bernie

Bambi Haggins / University of Michigan

Bernie Mac was at the center of my favorite sequence in The Original Kings of Comedy, which, strangely enough, did not actually depict the standup acts of the aforementioned “Kings.” The scene, one of the many offstage passages where Steve Harvey, D.L. Hughley, Cedric the Entertainer and Bernie Mac—all together, in pairs or individually—gave us a glimpse into the camaraderie between the band of comic brothers who had toured the country for two years on what might be referred to as the new Chitlin’ Circuit. The “Kings” were noticeably not playing on a basketball court in a park in Charlotte, North Carolina with the gray of both the asphalt and the sky framed by less than bright-and-shiny high-rise apartments. Dressed in a dark shirt, suspenders and dress slacks (both conservative and formal than his brethren), a bespectacled Mac made his case to the viewing public (as the other “Kings” chuckled and heckled him). “I’ve been with my wife for 25 yrs. I ain’t got no outside kids …but do I have a television show? No!” The comic removed his glasses with feigned intensity: “I ain’t got no television show. Heh!” Flashing a look of mock disdain, he declared, “[It’s] ‘cause you’re scared of me. Scared I’m gonna say something.” After a deliciously timed pause punctuated with a sly little smile, Mac admitted, “You’re motherfuckin right. Heh! Think I won’t say something. …You’ve been fucking with me for a long time …You told me to say what I wanted to say.” Mac then transformed into the penitent nice negro and implored, “White folks, I’m just playing…if you all just give me a chance…I’ll take WB, I’ll take UPN, I’ll take USA. Gimme a chance to show you—I’ll take TNT.” Bernie Mac was the only “King” without a kingdom (not even one on a netlet).

In May of 2001, as a media literacy outreach project for the Society of Cinema and Media Studies, a group of scholars including Beretta Smith-Shomade, Henry Jenkins and myself, worked with a predominantly African American group of students at Wilson Humanities, Arts and Media Academy in Washington D.C. The session culminated with group work, one scholar and 4-5 students had to “pitch” a television series—outlining the premise, the target audience, possible advertisers and network. The group pitching the series with the greatest merit was awarded a prize – gift certificates, if I recall correctly. The students I worked with quickly found consensus: they wanted to pitch a family comedy with Bernie Mac. Our group’s pitch was not given the green light by the faux network head, however, I hoped that they felt vindicated when The Bernie Mac Show premiered on Fox, several months later. I’ve often wondered whether they suspected that someone had stolen their brainchild. Nevertheless, there was something about Bernie that spoke to these kids, to actual network executives and to audience members who were Def Comedy Jam faithful and those for whom the Kings was an introduction to Black standup (beyond Cosby, Pryor and Murphy).1

Bernie Mac don’t sugarcoat.

Bernie Mac just says what you think but are afraid to say.

As Alan Sepinwall notes, the comic had three fairly distinct personae: “There’s Bernie Mac, the angry, hard-edged comic made famous to black audiences as part of the Original Kings of Comedy revue. There’s Bernie Mac, the cantankerous suburban dad at the center of Fox’s popular new sitcom of the same name. And there’s Bernie Mac, born Bernard McCullough, the 44-year-old Chicago son who has spent his entire life preparing for the popularity of his two alter egos.”2 Whether on stage or on the small screen, Bernie Mac was the purveyor of simultaneously ferocious and disarmingly honest form of what I like to call “candor comedy.” The aforementioned triplet, quoted in the comic’s act, series and numerous interviews, outline the tenets of Mac. You see them when watching the Bernie Mac who made his television debut on Russell Simmons’ Def Comedy Jam (in black-rimmed glasses, quasi-fade haircut, stone washed blue jeans stenciled with graffiti, a white shirt with primary colored squares on one side and multicolored colored circular designs on the other). In fact, from the very first line of his 8 minute set, you are convinced Bernie Mac was pretty much always Bernie Mac: “I ain’t scared of you motherfuckers. You don’t understand…” You see it, with a bit more polish but no less edge, when Mac is the headliner, dressed in the kind of silk-suited regalia befitting a “King” in the 2000 Spike Lee joint. The coda to his King’s set foreshadows his ability to explain things to “America” without falling into the trap of attempting to translate his actions, ethos or words for mainstream comfort; such is the case in his brief treatise on the word “motherfucker” as a person, place or thing as he models as possible conversation:

I’m gonna break it down to ya… If you’re out there this afternoon and you see like 3 or 4 brothers talkin’, you might hear a conversation and it goes like this: You seen that motherfuckin’ Bobby? That motherfucker owes me 35 motherfuckin’ dollars! He told me he gone pay my motherfuckin money last motherfuckin’ week. I aint seen this motherfucker yet! I’m not gonna chase this motherfucker for my 35 motherfuckin’ dollars. I called the motherfucker four motherfuckin’ times… but the motherfucker won’t call me back. I called his momma the other motherfuckin’ day… she gonna play like the motherfucker wasn’t in. I started to cuss her motherfuckin’ ass out, but I don’t want no motherfuckin’ trouble. But I’ll tell ya one motherfuckin’ thing… the next motherfuckin time I see this motherfucker… and he don’t have my motherfuckin’ money… I’m gonna bust – his – motherfuckin’ head! I’m OUT this motherfucker.

Often the comic’s persona is an id-infused condensation of the actual human being behind the mic; in other words, it was Mac2. “When I put that mike in that hole, I’m done with that guy. That guy that you’re talking to now is not the guy on stage. It takes me 15, 20 minutes to get into that guy. It takes me 30 minutes to let go. He’s so abrupt. He’s so nonstop. Bernie Mac is relentless. And that’s one thing I like about him. He doesn’t care what you say, he’s going out there to entertain that audience. And the people who come to see Bernie Mac, that’s what they want from him. And if I do anything different, I’ll be lying to myself.”3

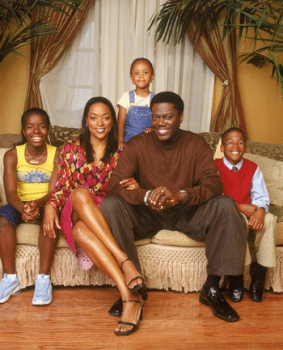

The other alter ego existed in a semi-autobiographical televisual space that afforded a construction of Bernie Mac as man at leisure and comic-as-domcom-dad that cut the intensity of the standup persona with the lived experiences of Bernard McCullough. The premise for the series was a product of Mac’s most recent stand up act. The Kings version of the setup was made ready for primetime and established the practice of his direct addresses to the audience, ”America, let’s talk. Yeah, my sister’s on drugs, that’s okay. Some of your family members messed up too.” Thus, began the domcom version of the actual lived experience chronicled in his act. Nessa (Camille Winbush), the teenager, Jordan (Jeremy Suarez), a bookish ten-year-old and Brianna AKA Baby Girl (Dee Dee Davis), the sitcom kids, were older and acted as foils to Mac (rather than the two, four and six years old sociopaths bent on his destruction as fictionalized in his Kings’ version). The battles are generational and regional as well as cultural: parents vs. children, wealthy Angelenos vs. poor/ working class Chicagoans, Civil Rights era, old school blackness vs. post-soul constructions of race. While successful comic Mac and his gorgeous business executive wife, Wanda (Kellita Smith), had attained their hard won piece of the American Dream, their new brood had only experienced the dream deferred, as it were.

As series creator, Larry Wilmore noted:

The word that we used a lot was authentic…We wanted something to feel authentic, look authentic, and for me and Bernie, it was really important that he be in a loving relationship with his wife. That’s what I really wanted to see on TV, you know, these two people who were there for each other, and that the conflict was with these children, who he considered terrorists. …every single scene on that show is about negotiating with terrorists… The difference being that he loved those kids to death, you know, that they were really like his kids.4

In keeping, some of the funniest material in Mac’s act as in the sitcom was rooted in the abrasive and often hostile parenting style (“If you’re old enough to talk back, then you’re old enough to get knocked the fuck out,” or “Bust your head until the white meat shows.” Yet amidst these amusing quips, the Peabody award winning series, revised and revisited notions of extended family both in their quasi-nuclear clan or the Macs from all over the country (in the hilarious family reunion episode). Depicting the black family dealing with nuances of class, region, religious practice and gender norms, not in very special episodes but as a part of the series’ life, separated The Bernie Mac Show from other Black domcoms and domcoms in general.

Upon hearing about the passing of Bernie Mac, my good friend, Raj Mahal, declared, “Bernie wasn’t just a black comic—he was BLACK inside and out.” I understood what Raj was saying—and it was not a statement about color politics. As fellow “King,” D.L. Hughley stated after Mac’s passing, “[Bernie] was a touchstone between the old way of comedy and the new way of comedy. … I think the hardest thing to be, as a black man, is an individual.”5 Bernie Mac spoke for Bernie Mac and in so doing his comedy—abrasive, sometimes blue, sometimes sentimental—gave voice to a Black experience that refused to be seen as monolithic while inviting identification.

Not long before his death, Mac decided to forego standup to concentrate on his film career.6. Mac did, however, leave his fans with his last comic hurrah, captured in the documentary, The Whole Truth, Nothing But the Truth, So Help Me Mac. I will always regret missing out on watching Mac perform live in the same way that I regret never having seen Richard Pryor, Moms Mabley or Redd Foxx. As student of comedy, who is also a fan, you come to appreciate the rare comic who can play to and with an audience, who can shock while endearing himself to you, who is fearless, sometimes offensive, and always original—and that was the “something” that made Bernie Mac Bernie Mac.

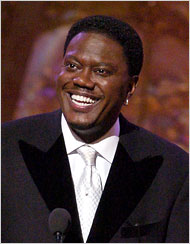

Image Credits:

1) Bernie Mac…The Original Kings of Comedy

2) The Late Great Bernie Mac

3) Bernie Mac in Universal City

4) The Family Mac

Please feel free to comment.

- I have chosen not to focus on Mac’s film career because I believe that his artistic legacy can be most easily discerned in those moments when he talked to directly to us—whether from behind a microphone or when he spoke, comfortably ensconced in the chair in his television den, talking to America. [↩]

- Sepinwall, Alan. “Bernie Mac: In his own words.” The Star-Ledger. Saturday August 09, 2008, 12:18 PM

http://www.nj.com/entertainment/tv/index.ssf/2008/08/bernie_mac_in_his_own_words.html accessed Sept. 10, 2007.

[↩] - Gray, Ellen. “Mac attack: Bernie talks (and talks, and talks) about himself.” Knight Ridder Tribune News Service. Washington: Mar 1, 2002: 1 [↩]

- Sepinwall. [↩]

- King, Larry. “A Tribute to Bernie Mac.” Larry King Live. CNN. August 12, 2008. [↩]

- Malcolm Lee’s music-infused, buddy road movie, Soul Men, co-starring Mac, Samuel L. Jackson and the late Isaac Hayes, will be released in summer 2009. [↩]