Hey, hey, ho, ho – Video-game censorship has got to go

Aaron Delwiche / Trinity University

Five weeks ago, approximately two dozen anti-war protestors marched on Ubisoft’s offices in San Francisco. Organized by the group Direct Action to Stop the War (DASW), the demonstration targeted the French game developer for “porting” the game America’s Army from the PC to the Xbox 360 home gaming console. Activists objected to the game’s sanitized representations of warfare, and criticized its developers for deliberately “toning down the gore” in order to secure a “teen” ESRB rating, making it possible to market the game to thirteen-year olds.

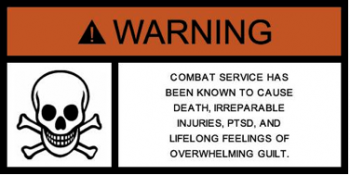

Disturbed by the game’s seamless integration with virtual army recruiting centers, demonstrators urged Ubisoft to package the game with consumer safety labels stating:

“Warning: The video game America’s Army has been developed by the United States Army to recruit children under the age of 17 in violation of the U.N. Optional Protocol and international law. Combat service has been known to cause death, irreparable injuries, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and lifelong feelings of overwhelming guilt.”

In targeting America’s Army, the DASW chose a “brand” that has been actively reaching out to high school students, gamers and games researchers for most of this decade. Developed for the US Army by the Modeling, Simulation and Virtual Environments Institute (MOVES) at the Naval Postgraduate School, America’s Army is a free, downloadable game that leverages the conventions of the first-person shooter game genre to recruit young Americans into military service. Boasting more than 9 million registered users as of September 2008, it has been described as “the most successful game launch in history” (O’ Hagan, 2004).1 During the past five years, America’s Army and other game designers affiliated with the military have also played a vital role in building a “serious games movement” that leverages the power of video-games for education, corporate training, public policy, and (of course) combat training.

Although many in the gaming industry are quick to renounce critics of militaristic and violent video-games, senior Ubisoft representatives met with activists and listened to their concerns. According to one unverified account, representatives acknowledged that the thinly veiled recruitment tool had generated “internal conflict” within the company. In a statement subsequently e-mailed to Wired Magazine’s Chris Kohler (2008),2 Ubisoft representatives stated that “we respect DASW’s First Amendment rights, and would hope they also respect and recognize ours.”

Ubisoft’s reference to the importance of free speech might strike some as a predictable corporate response, but the company’s representatives make a crucial point. Warning labels are not the answer.

The use of video-games for youth-oriented military recruitment propaganda is a deeply troubling trend, and more Americans should be paying attention to these developments. The Iraq War is increasingly perceived – domestically and internationally – as a tragic military intervention that was sold to the public with a web of unsubstantiated claims and half-truths. The DASW is right to draw attention to the blatant propaganda themes in America’s Army, but the organization’s call for game censorship is seriously misguided. Warning labels are just as unpalatable when promoted by anti-war activists seeking to regulate video-games as they were in the mid-1980s when the Parents Music Resource Center attempted to label Prince and Madonna albums that contained “offensive sexual content.”

In addition to the free-speech issues, it is naïve to think that the US Army is the only entity that actively uses video-games to persuade and propagandize consumers. The market for video-game advertising currently exceeds $1 billion, and this figure is expected to reach $2.3 billion within the next four years. A portion of this money is spent on traditional product placement in franchises such as Guitar Hero and Need for Speed, but advertisers have woken up to the fact that interactive media can deliver entertainment experiences that are essentially playable commercials. America’s Army may have been among the first to integrate narrative and game-play mechanics with political and commercial objectives, but it is just the tip of the iceberg. Rather than sticking labels on games like America’s Army, we should be teaching students to think critically about the messages embedded in all video-games.

Rather than censoring existing games, media literacy activists and games researchers should work together to design an analytical framework that can help students to think more critically about the medium of video-games. Unfortunately, the media literacy movement’s existing tools are insufficient.

Educators regularly criticize titles like Grand Theft Auto and Fat Princess for violent, racist and sexist representations, but there has been little sustained attention to the underlying characteristics of video-games that make them such powerful persuasive tools. As Steven Poole (2003)3 points out, “videogames are an increasingly pervasive part of the modern cultural landscape, but we have no way of speaking critically about them” (12).

At the interpretive level, a robust video game literacy framework would help students articulate a basic understanding of such essential video-game characteristics as immersion, intense engagement, identification and interactivity (Delwiche, 2007).4 These interpretive efforts could be supplemented by activities that encourage students to engage in the creative aspects of game design. As Renee Hobbs (2005)5 notes, “producing media messages has long been understood as one of the most valuable methods to gain insight on how messages are constructed” (20).

In many educational settings, hands-on computer access for each student in the classroom is not possible. The good news is that one can involve students in game design without complex computer programming courses, intensive tutorials in 3D modeling, or access to cutting edge computer equipment. Conceptual design exercises, cheat codes, and mod authoring tool-kits are just a few ways in which students can modify existing games or create entirely new ones.

For example, in 2002, Anne-Marie Schleiner created a mod called Velvet Strike that subverted the ideological messages embedded within the game Counter Strike. Schleiner’s mod made it possible for politically minded users to create and disseminate “spray-paint skins” that would quietly insert anti-war graffiti into multiplayer battlefield terrains. With this relatively straight-forward mod, which was covered by newspapers around the world, she managed to ignite a thoughtful discussion of video-game militarism (King, 2002).6

Velvet Strike is demonstrates the creative potential of mods and other tools that foster user-generated game content. Above all else, Velvet Strike reminds us that spreading our own messages is one of the most effective ways of countering ideas that we find objectionable.

Across all forms of media, the best remedy for offensive speech is more speech, not censorship. As Justice Potter Stewart observed in the context of the 1966 Ginsberg decision, “censorship reflects a society’s lack of confidence in itself. It is the hallmark of an authoritarian regime.”

Image Credits:

1. America’s Army: Official video game of the United States Army

2. In August 2008, approximately two dozen protesters congregated on the headquarters of the company that is porting America’s Army to the Xbox 360. In the image above, an Iraq War veteran, Ryan Lockwood, peers into the Ubisoft offices.

3. Even when one agrees with the underlying sentiments, warning labels are a bad idea. It is possible to bolster young people’s defenses against noxious propaganda with educational methods that are more effective and less intrusive. Label created with DSAW text and the on-line warning label generator at http://www.warninglabelgenerator.com.

4. These spray-paint skins for Velvet Strike can be found on the mod’s primary site: Velvet-Strike: Counter-military graffiti for CS.

Please feel free to comment.

- O’ Hagan, S. (2004) “Recruitment hard drive: The US Army is the world’s biggest games developer, pumping billions into new software,” The Guardian (London), June 19. [↩]

- Kohler, C. (2008) “Activists protest America’s Army game with songs and stickers,” Wired Blog Network, August 6th. Accessed on August 29, 2008 at http://blog.wired.com/games/2008/08/ubisoft-protest.html [↩]

- Poole, S. (2000). Trigger happy: videogames and the entertainment revolution. New York: Arcade Pub. [↩]

- Delwiche, A. (2007) “From Green Berets to America’s Army: Videogames as a vehicle for political propaganda” in Williams, J. P. and Heide-Smith, J. (Eds.), The Player’s Realm: Studies on the culture of video-games and gaming. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. [↩]

- Hobbs, R. (2005, March). Strengthening Media Education in the Twenty-first Century: Opportunities for the State of Pennsylvania. Arts Education Policy Review, 106(4), 13-23. [↩]

- King, B. (2002) “Make love, not war games,” Wired Magazine, June 8th. Accessed on August 29, 2008 at http://www.wired.com/gaming/gamingreviews/news/2002/06/52894. [↩]

Great article, Aaron. And I agree; censorship is not a functional way to deal with content deemed inappropriate or undesirable.

Right now I’m thinking of Flow’s home university, UT, and the ACTLab, which is housed in its Radio-TV-Film department. The ACTLab offers “studio” courses in which students undermine, co-opt and repurpose daily technologies (and theoretical frameworks). It’s the kind of space that can offer students the video game literacy framework that you have called for. It’s only too bad such courses are not always offered at the university level, and are even rarer in middle and high schools, where we need them most.

Aaron, thanks for the insightful column. Touching on the topic of the Army’s recruitment efforts towards youth, there are more than just video games to worry about. This past year, the US Army teamed up with MTV to promote and sponsor the latest Real World/Road Rules Challenge. It is frightening to think of how wide the Army’s recruiting net has been thrown. One can hope that the people consuming the different Army media are aware of the counter-narratives and arguments against war.

Great article, very insightful. I haven’t heard much about this game in such a long time, thank you for bringing up an important issue that often goes ignored.

From what I know about America’s Army, its largely praised for its attention to technical details (a surprisingly accurate adventure in military technocracy) and criticized for its repression of the brutal realities of warfare. In that way, the game seems analogous to War War II documentary films (specifically Frank Capra’s Why We Fight series, and John Ford’s The Battle of Midway) in a lot of interesting ways. Of course they’re both works of propaganda, but these documentary films were interesting blends of technical fact and fiction: John Ford filmed the Battle of Midway himself with a handheld camera, even getting wounded by enemy fire; but he also staged much of the naval battle in a Hollywood studio, and the film never differentiates between actual combat footage and staged scenes — an early militarized hyperreality. The American public didn’t develop a critical eye towards film, especially documentary film, over night. I wonder in which ways the development of that discourse parallels that of video games?

Pingback: Stand To Digest Sept 5- Sept 10 2008 - Freemason Hirams Travels Masonic Forums

share with NH VFP and MCAM

this game is not designed to recruit the youth at any point the game was designed for one purpose and thats to show the people that want to join the army what its like to be in a combat situation the fact of trying to recruit kids under 17 is bogus the army has no need for them