Same As It Never Was: Nostalgia and Children’s TV

Karen Lury / University of Glasgow

In the last class for a course I taught on children’s television, I decided to use the theme of nostalgia. It seemed appropriate as the class was largely made up of final year students, some of whom I had taught for four years. I set readings from Henry Jenkins (on the various television series of Lassie),1 one of Adam Philips’ essays in The Beast in the Nursery2 and a chapter from Stuart Jeffries’ childhood memoir, Mrs. Slocombe’s Pussy.3 For the screening, I chose one programme, Pogle’s Wood, shown on the BBC in 1966-1968 and some of the students’ choices, which included a children’s pre-school show Playdays, an animated series The Animals of Farthing Wood, as well as a 1980s BBC adaptation of Five Children and It (obviously most of the class had been children in the 1980s). The screenings had been selected via a poll of favourite children’s programmes that ran throughout the eight weeks of the course, on a shared website. At the beginning of this last class I asked them to write a few thoughts about why they had chosen the programmes and what they had felt about seeing them now – as adults and in a non-domestic context. This column is a response to their and my own thoughts about our memories of children’s television.

I began the class – as Jenkins begins his essay – with a citation from Susan Stewart’s book, On Longing:

Nostalgia is a sadness without an object, a sadness which creates a longing that of necessity is inauthentic because it does not take part in lived experience…Nostalgia, like any form of narrative, is always ideological: the past it seeks has never existed except as narrative, and hence, always absent, that past continually threatens to reproduce itself as a felt lack.((Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the miniature, the gigantic, the souvenir, the collection4

Ironically, in the discussion during that class and elsewhere on the course, children’s television revealed itself to be not an object or at least not the kind of object that we usually associate with nostalgic longing. For while it was, in a sense, tangible – we had been able to retrieve at least some of the programmes the students remembered and nearly all were available as fragments on YouTube – in terms of the viewing experience, television remained obstinately ephemeral: we couldn’t recreate or reproduce the ‘first time’ or habitual past experience of watching children’s television. And in their written recollections it was often these aspects, rather than the programmes, plots or characters, that were the most ‘sticky’ in terms of desire and memory (often literally!) Students remembered vivid sensual and kinetic experiences – eating yoghurt and mashed bananas, running around the room, tiptoeing past a sleeping Dad on a Saturday morning, being shouted at by Gran, making pens into Ninja turtles – but they had often forgotten plot lines or the visual aesthetics of the programmes (interestingly, not the musical or vocal themes and catchphrases.) It was this quality of the memories that made me think of another observation made by Stewart:

Speech leaves no mark in space; like gesture, it exists in its immediate context and can reappear only in another’s voice, another’s body, even if that other is the same speaker transformed by history. But writing contaminates; writing leaves its trace, a trace beyond the life of the body.5

It seemed to me that in our recollection, children’s television emerged as somewhere between speech and writing; and I began to see that there was something important about that intangibility. On the one hand, it was difficult to recall exactly what was felt about a programme or why. The embodied quality of that past has disappeared, yet there were elements of that experience available or trace-able within the programme text. Yet as the class and I discovered, there was never either a true, or a sufficient correspondence between what you could remember (what you thought you remembered) and what you heard and saw again (what we could locate in the programmes themselves.)

As Roger Silverstone suggested, it may be that television acts as a transitional object.6 That is, it bridges the interior world of the self, which is, in infancy, without words but nonetheless strongly felt, to an exterior world, full of symbols which refer and conceptualise meaning and emotion and which allow us to communicate with one another. Indeed, the channels of exchange in children’s television are often concerned explicitly with the passage of sounds into words, and words into explanations. Equally, many shows conceptualise emotions but also allow space for the free range of those emotions, although tears are surprisingly far less common than you might remember.

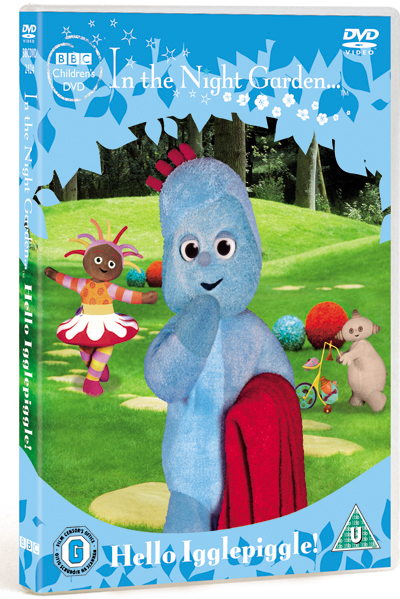

Children’s television confirms that meaningful communication is possible without words. This is evident, for example, in the nonsense language of the creatures in the BBC’s newest pre-school ‘hit’, In the Night Garden. Yet writing is only possible if there are words and as an overtly pedagogic genre, children’s television frequently encompasses both wordless nonsense and meaningful language. It produces nonsense by letting characters babble but somehow communicate (‘Iggle Piggle!’) or by emphasising expressive communication – colour, sound, emotion – in a way that makes these formal elements ‘meaningful in themselves’. Yet in other programmes, or in the same programme, pictures and feelings are often made sense of as they are put into words. I think this dynamic, which is not just one way (from sounds to words but words into sounds) creates a strong, affective framework for nostalgia that reveals it to be not a narrative, but more haphazard, more akin to a musical sensibility (a musical comprehension?) rather than a linguistic chain of events. It is not coincidental that sounds – stings, phrases, timbre and accent – were more frequently recalled than images and plot details. In my case, remembering The Pogles was about tone of voice: Mr. Pogle’s ‘yokel’ accent and my memory of my mother’s voice as she imitated him. This was related to my fragmented rememberings of a rural childhood, a tactile, sensual recollection, of damp woods and the smell of leaf mulch rather than the moral lessons that I now realise the programme wished to tell me. Of course, these are just parts of that childhood: what I’m suppressing is the boredom, rain, cold and loneliness. Jenkins’ comments in relation to his childhood and Lassie and on the distinction between the reality and fantasy of dog owning is pertinent here.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0pXnprQvSA[/youtube]

If children’s television mediates the transition from one kind of self-hood (interior, expressive, wordless, and alone) to another (exterior, conceptualised, word bound, and accompanied) it does so at a cost. For, as Adam Philips suggests, we necessarily leave something behind. He argues that although growing up is a necessity, there is also something lost in this process – or maybe not lost, but irretrievable in any way that we can make sense of it, or make proper use of it. He suggests that at different times it may be about:

‘the irregular…the oddity, the unpredictability of what each person makes of what is given; the singularity borne of each person’s distinctive history.’7

And there is a tension between wanting to reclaim the peculiar – the singularity of our own history – with the need to share that experience with others. Although it was always good natured, the acclaim for some programmes and the dismissal of others, or complaints that I didn’t select certain programmes, was a fairly consistent factor on the website. What seemed to be happening was a negotiation of a nostalgic longing that was personal – for me it was the sound of my mother’s voice – juxtaposed with a desire to see that nostalgia legitimated by others who shared the same longing for a specific text.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sPz1Zy98bJw[/youtube]

It is in the interests of television producers that we feel that we might find our ‘singularities’ in texts that are shared by many others: nostalgia is a market as well as a personal experience. It is therefore not surprising that in the short time since the publication of Jeffries’ book many of the children’s programmes he mentions from the 1970s have been remade, or continue to evolve. New versions, repeats or evolutions of older programmes appeal to a generation of parents who remember the programmes and feel comfortable in letting their children watch these shows. Firstly, because they are remembered as safe; secondly it may be that they offer the promise that the unknowable interior of their children might become more comprehensible or accessible. Yet, as the students and I discussed our reasons for liking, loving and loathing particular programmes, it became evident that the ‘lost objects’ of our nostalgic exercise – childhood and television – were not and could not be the same things for everyone. Indeed, as Jenkins also concludes:

In the end, nostalgia always frustrates the desires that fuel its search for a more perfect past. We can’t trust our feelings, memories, or myths. Things are not the same. They never were.8

Same as it never was.

Image Credits:

1. Family portrait from Pogle’s Wood

2. Iggle Piggle on the DVD cover for In the Night Garden

3. Front Page Pogle’s Wood Image

Please feel free to comment.

- Henry Jenkins, “Her Suffering Aristocratic Majesty”: The sentimental value of Lassie, in Marsha Kinder (ed.) Kids’ Media Culture, (Durham and London: Duke University press, 1999) pp. 69-102 [↩]

- Adam Philips, ‘The Beast in the Nursery’, from The Beast in the Nursery, (London: Faber and Faber, 1998) pp. 37-60 [↩]

- Stuart Jeffries, ‘1967: Bill and Ben’s hats (children’s TV) in Mrs. Slocombe’s Pussy: Growing up in front of the telly, (London: Flamingo, 2000) pp.1-39 [↩]

- Durham and London: Duke University Press, [new ed.] 1993) p. 23 [↩]

- Ibid, p. 31 [↩]

- Roger Silverstone, Television and Everyday Life, (London: Routledge, 1994). [↩]

- Philips, op cit, p.38 [↩]

- Jenkins, op cit. p.98 [↩]

I definitely have to agree. When thinking back to my favorite childhood TV shows, my sister is always in my memories. We pretty much only watched TV together and when I think about shows, it’s the conversations or laughs or arguments she and I would have about those shows that I remember. Likewise, I have very fond memories of Fraggle Rock and when I stop to think about it, the only time I ever remember watching it was in the mornings when we’d eat our cereal before school. I couldn’t tell you one plot line, but I can tell you we ate Cheerios and watched it every morning at 6:30.

Also, I just saw Wall-E yesterday and that is definitely an example of children’s entertainment which relies on the babble as a form of communication (and it’s done so well!).

I agree as well. When the Simpsons first hit the air, I was 7, and my parents made viewing a family ritual. It was the only night of the week we were allowed to eat in the living room, and we, as a family, would sit on the couch with our plates of food and watch the show, which was being loudly condemned by most of our neighbors as utter filth. While I still love the Simpsons, I’ve realized over the years that the first few seasons are of terrible animation quality — the show’s increased budget over the years definitely shows. However, the thrill of being allowed to eat in the living room and of being in with my family members on a blatant disregard for the community standards of our neighborhood was absolutely intoxicating.

PBS’s Square One = Home alone, no mom, math games, Capri Suns, becoming a self-sufficient older child….who no longer needed Reading Rainbow. So much of the experience was glee at growing beyond the other shows, and holding that growth over my younger brother, taunting him with my greater understanding. Nostalgia can also be for a moment of superiority, of knowing, and the comfort both bring.

Watching pogles wood actually hurts my heart.loved it so much as a child.