Into the Maelstrom with Flavor of Love

Jennifer Fuller / University of Texas – Austin

In the article “New Ethnicities,” Stuart Hall described a new phase of black cultural politics, one that marked the “end of the innocent notion of the essential black subject,” that is, the end of the belief in a fundamental sense of ‘blackness’ that could effectively represent black people as a whole.1 This new phase would displace but not replace the cultural politics that called for new “positive” representations in place of the old “negative” ones. The new phase would be marked by cultural and representational strategies that would acknowledge the diversity of black experiences and expressions.

That was twenty years ago. And while there have been some significant departures, the faith in “positive representations,” (images deemed to be the free of stereotype) is still dominant, with most of its attendant middle-class tastes and normative notions about gender and sexuality intact. In 1999, during the NAACP campaign against the dearth of minority representations on the Big 4 networks, president Kwesi Mfume called for not just more black characters on television, but in ‘quality’ shows, which were often about medical and legal professionals, instead of in ‘ghetto’ sitcoms, which were infused with black vernacular language, culture and humor. More recently, VH1 reality show Flavor of Love (2006-2008) has been lambasted by critics for its portrayal of black women as ignorant, combative and hypersexual jezebels in a phony contest for the affections of Flavor Flav, a black cultural icon (as a member of rap group Public Enemy) who had become a flashy, no-count coon. In the quasi-corrective Flavor of Love Girls: Charm School (VH1, 2007), headmistress comedian Mo’Nique stripped the women (including nonblack contestants) of the nicknames Flav gave them, and urged them to shed the lewdness, loudness and generally unladylike behavior they displayed in Flavor of Love. The subtext, that their behavior reflected badly on the black race, was most explicit in the reunion episode, when Mo’Nique scolded feuding friends with: “They are watching us.”

There are very good reasons why people cleave to the ‘old’ ways. As Hall says, the call for positive representations was a response to the “fetishization, objectification and negative figuration” of blackness in society and the mass media, and those discursive practices surely persist. This pattern of social and representational domination gives rise to black double-consciousness, the burden of seeing ourselves as whites see us. Double consciousness hounds us as we consume, produce and analyze media: “They are watching us.” I still want to champion the displacement of “positive images” as a cultural strategy, because the insistence on the “positive” limits black representation in classed, gendered and sexualized ways (“ghetto,” “unladylike”) . That is not to say that we can’t ever say that we don’t like certain imagery. Quite the contrary. But we should focus on the dynamics of representation itself by considering how ideological and industrial constraints that help to limit representations of blackness. To illustrate this, I’m going to talk about the widely-reviled Flavor of Love.

First, I’ll make the necessary claim: I’m a Flavor of Love fan. Now, I’ll address the necessary question: “How do you watch that show?” The answer: “Very carefully.” I negotiate my way through Flavor of Love like I negotiate my way through all other texts. My fandom informs my analysis, but I don’t believe that the show is necessarily ‘good’ (politically or aesthetically) or unproblematic because I like it. I know that many people consider the show to be simply irredeemable; my goal here is to show that Flavor of Love isn’t “simply” anything. There are aspects of the show that I can’t accept, and aspects that I appreciate; I give an example of each here. As Hall wrote, “Once you enter the politics of the end of the essential black subject you are plunged headlong into the maelstrom of a continuously contingent, unguaranteed, political argument and debate: a critical politics, a politics of criticisms”. That’s where and how I hope my viewing of the show happens. So, into the maelstrom we go…

Flavor of Love is problematic, but there been racial moments that were so hard to negotiate that they stopped me cold. One was a segment when Flav was narrating the show as usual, giving his insights and telling jokes. But this time, he was gesticulating with a piece of fried chicken. It was a brief moment, and may seem insignificant in the grand scheme of the show. But that moment was disturbing because it gave traction to the charge that Flav had sold out his political beliefs. A recent headline sums up this view: “The Journey of Flavor Flav: From Public Enemy to Public Buffon.”2 And Flav does indeed bear a striking resemblance to the buffoon, or ‘coon,’ stereotype. But a look at Public Enemy’s videos reveals that he hasn’t changed much: Flavor Flav is not a VH1 invention. Even then, Flav was impish and ostentatious, bouncing around and mugging for the camera, sporting outsized sunglasses and multiple clocks, extreme hair, and a mouthful of gold teeth. Indeed, the “dandy” coon stereotype mocks the flashiness that is often valued as a part of black personal style – instead of accusing Flav of drifting (or dancing) toward the stereotype, it is important to think about how the stereotype limits how we perceive Flav in the first place. Ultimately, Flav can be outrageous in style and behavior; that doesn’t make him a ‘coon.’ In fact, it was his style and charisma that made him hip-hop’s “greatest hype man.”

Flav flirted with the ‘coon’ stereotype for years. The 1991 video for “Burn Hollywood Burn” skewers black stereotypes, but also shows Flav eating barbecued ribs while meeting with a white film executive. Flav eats straight out of a Styrofoam container, and props his feet up on the executive’s desk, creating an image that is strikingly similar to those criticized by the video itself. But when the executive makes it clear that he wants Flav to play a “servant that shuffles a lot,” Flav jumps up, indignant. Without the black nationalist context, in Flavor of Love there is no moment of indignation, at least not on-screen. Although he might still be a trickster, an intellectual disguised as a fool (that is, if he really ever was), the dating reality show genre doesn’t allow for this. In spite of all our media savvy and cynicism, the genre’s stock-in-trade is still the putative earnestness of everyone involved.

Speaking of which, I want to briefly discuss two contestants from the third season. Twins Latrisha and Latresha, who Flav named “Thing 1” and “Thing 2,” confound a simple dismissal of the Flavor of Love contestants as hoochies and harridans. Thing 1 and Thing 2 captivated Flav, and in the last episode, it was Thing 2 who won Flav’s affections (temporarily). They were fan favorites because they seemed sincere. I argue that this sincerity was partly indebted to the “realness” signified by the twins’ working-class style. They were ‘around-the-way girls,’ complete with black English and doorknocker earrings. It also stemmed from the twins’ sweetness, which was especially delightful in a genre where the ‘tough girl’ is a favorite black female caricature. Granted, Thing 1 and Thing 2 could be just as contentious as the rest, intimidating and shouting down other contestants. But they also often draped their arms around each other, and had a habit of tilting their heads to one side and speaking in lilting tones. I am cautious about praising girlishness in images of grown women, but mainly for the reason that I appreciate it here. Girlishness is a kind of femininity that is rarely extended to black women, a construction that makes vulnerability a privilege of the powerful. White women can be dainty, foolish, and socially awkward, even (or especially) if it is just a prelude to them rallying their emotional strength or physical prowess. Meanwhile, their black counterparts have to be knowing and tough at all times. In contrast, the twins’ vulnerability was on display, including when they wept openly, eliciting tears from other members of the cast, and Flav as well. To be perfectly clear, I don’t think that weeping vulnerability is inherently good, but I was glad to see this side of black femininity represented.

Again, my goal wasn’t to suggest that Flavor of Love is politically “good.” I wanted to show that it is politically complex, and did so by considering aspects of the show in the context of the genre, across axes of identity, and across texts. Twenty years after the publication of “New Ethnicities,” Flavor of Love’s clock motif is especially fitting. The displacement of the “positive representation” stance is long overdue, but so is that diversity representation of black subjectivities. As we work toward it, we should be mindful enough and brave enough to consider the cost of privileging the educated, middle-class, chastely heterosexual flavor of blackness as the only “positive” one, no matter who is watching.3

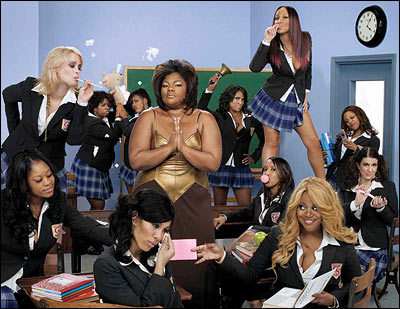

Image Credits:

1. Flavor Flav

2. Mo’Nique and the contestants of Charm School

Please feel free to comment.

- Hall, Stuart. “New Ethnicities.” Reprinted in Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, 441-449. New York: Routledge, 1996 [↩]

- The article discusses Flavor of Love as well as Flav’s zany new sitcom, Under One Roof (CW, 2008). [↩]

- Flav’s on-screen affairs with white women, starting with Brigitte Nielsen in Surreal Life (2004) and Strange Love (2005), are also used as evidence that he has given up his black nationalist politics. See Trailer 2 (available on YouTube) for former Public Enemy member Professor Griff’s 2007 documentary Turn Off Channel Zero [↩]

Like you, I am too a Flavor of Love fan! (there, I said it). Flav’s self-representation, as you point out, has not changed much from his years in Public Enemy. He was always flashy, hyper, and sometimes plain silly (at least to me). Yet, for his career to have basically come back from the dead, and with the force that it has, Flav certainly must play the trickster–in order to navigate higher-ups in the business, the women who live in the house, his family and friends, and certainly his fans. I watched the show not because I was interested in Flav, but because I could not get over, or sometimes fully comprehend the gender dynamics at work. Every week after the show was over, I would say to my partner, “that’s it we are not watching this show ever again!’ Then I would sit there and watch another hour, and another, plus reunions. I understand your point about the “softer” femininity and “genuineness” projected by Thing 1 and 2 in last season’s show, but for me the more iconic female character to emerge from the show is Tiffany aka New York. How/what are we to think about New York? I do not believe she is simply a female replica of Flav. She couldn’t be. She is a reality TV newcomer, with no lineage in the show business. One of the more striking things about New York, aside from her exuberant, drag-queen-like persona, is her sidekick Sister Patterson (also her mother). (Many fans questions that this woman is actually her mother). What are we to make of this dynamic duo? Why did New York need such a strong female sidekick, while Flav did not? And moreover, what are we to make of the obviously class-based (and possibly racist) disdain Sister Patterson so passionately felt for Flav?

This article is amazing and teases out the complexity in a series – that I must admit as a black woman – I can’t bring myself to watch. I also would like you to follow this up with a critique of either “I Love New York” or “Shot at love with Tila Tequila” both are guilty pleasures starring women who got their starts in reality TV or new media (My Space). The possibilities are endless.

Thanks, Jennifer, for such a thoughtful piece! I’ve been waiting for someone to write something smart about Flavor of Love….

For me, your observations about the limitations of role-model analysis (positive v. negative imagery) are right on; they not only oversimplify the televisual text, but unwittingly militate against complex and diverse African American portrayals. I can’t wait to use this in my African Americans and TV class this fall.

Thanks for the comments. I have a few thoughts about “New York.”

She is an interesting phenomenon. I remember puzzling over her class position, because although she seemed middle-class in many ways (a ‘vibe’ that was even more solidified when her parents showed up), she didn’t perform the “respectable” femininity and sexuality that many black women feel compelled to uphold. She was profane, she smoked, she got drunk, she fought, and of course, she was chasing after Flav.

I didn’t enjoy the one episode I’ve seen of “New York Goes to Hollywood” – she’s without her signature flair and charisma. She’s the comic – she needs her straight men (so to speak). However, the promotional campaign/opening credit sequence is fascinating. New York is dressed as Marilyn Monroe (in the famous “Seven Year Itch” air grate imagery), Forrest Gump and Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz – and in all cases, we are supposed to laugh at how ridiculous it is to imagine her in those roles because she lacks their innocence (even Marilyn’s ‘innocently seductive’ schtick). In some troubling ways, New York becomes the butt of the joke (even more so than in the two FoL seasons) because her delightful excess and her brand of black femininity become the obstacles that she has to surmount in order to be successful. Plus, she just looks ridiculous the wigs they put on her…

http://www.vh1.com/shows/serie.....lash.jhtml

Flavor of Love is a very interesting example of both blackness and femininity on television. The aspect of blackness here seems over-exaggerated. The women in the house are all stereotypically black; they are loud and combative and ostentatious, and Flavor Flav himself follows suit. One has to ask, what kind of representation is this? How does the editing and format of the show play these stereotypes up? The appearance of Thing 1 and Thing 2 serve to contrast this stereotype of loud, aggressive black women. They are sweet and seem fragile, showing that not all black women are defensive and boisterous. This show revolves around creating a spectacle, and having watched it myself, it seemed overly ridiculous to me. A group of young, attractive women are fighting each other (often physically) for the attentions of a man who is old enough to be their father. At the bottom of it all is this search to strip away whatever facades the women put up to attract his attention and find “true love.” While the show exploits blackness to some extent, it also centers around the message that beauty is deeper than just appearances.

This article discusses Flavor Flav and his transition from a hip-hop icon in the rap group Public Enemy to the host of Flavor of Love, where women try to earn his affection in the competition to come out on top. This helped to inspire Flavor of Love Girls: Charm School where women are transformed from their original, obnoxious selves into something more lady like. But the focus is on Flav, who is called a “coon” in the article. This references Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Donald Bogle’s article “Black Beginnings: From Uncle Tom’s Cabin to The Birth of a Nation.” A coon is described in the reader article as “those unreliable, crazy, lazy, subhuman creatures good for nothing more than eating watermelons, stealing chickens, shooting crap, or butchering the English language” (6). The article describes Flav’s show as a “ghetto” sitcom, “infused with black vernacular language, culture and humor” (Fuller). Also noted is how in one episode of Flavor of Love, Flav was sitting around, talking and eating a piece of fried chicken, feeding into the coon idea and the stereotype of how black people love fried chicken. As well, this is seen in Public Enemy’s music video “Burn Hollywood Burn,” mentioned in Fuller’s article. A short scene has Flav “eating barbecued ribs while meeting with a white film executive” (Fuller). He evens put his feet up on the man’s desk. This creates the lazy, rude black stereotype that the coon description describes.

Another idea represented in this article is the fact of acting black vs. acting white. In Charm School, where the girls are conditioned from their outlandish selves into polite and dainty women, this can be seen as a change from black to white behavior. They are trying to make these women, whether they are black or not, into “typical, white ladies.” In a season of Flavor of Love, twins nicknamed Thing 1 and Thing 2 exemplified “white behavior” on the show. They were portrayed as girly; Fuller says this “is a kind of femininity that is rarely extended to black women, a construction that makes vulnerability a privilege of the powerful. White women can be dainty, foolish, and socially awkward, even (or especially) if it is just a prelude to them rallying their emotional strength or physical prowess. Meanwhile, their black counterparts have to be knowing and tough at all times.” The fact that the twins showed they were vulnerable and could cry and whatnot made them “no longer black.” Why does how people of different races act have to dictate what is stereotyped as white and as black. It seems that even when a black person “acts in a normal way,” it is quickly labeled as “acting white.” This is what Darnell Hunt’s article “Making Sense of Blackness on Television” in the reader discusses. We are used to “…images of a black culture that breeds dangerous, lazy and ignorant blacks. Whiteness, in contrast, has become an unspoken proxy for goodness…Whiteness represents the cultural norm, the implicit standard from which blackness deviates” (144). There should be more “positive representations” of blackness in society today.

The show’s racial representations are among a myriad of similarly structured shows dealing with the borders of entertainment and race. I feel like television culture has already bypassed a phase or paradigm shift from “negative” to “positive” images of blackness and instead lives in a continually restricted format. Using Darnell Hunt’s notion of blackness as permeating every channel and reliant on racial binary coding; it seems hard to view this show as anything but a reactionary but limitedly positioned racial depiction. You describe “quality” programs (aimed at white middle class) as showcasing positive images of blackness, but those representations become uniquely problematic as they promote color blind social relations and middle class values like The Cosby Show. Do those images really constitute “positive” or do they serve as false idols? Just as you mention Flav’s status as sellout in his use of black stereotype; is the parody and satire of these constructed stereotypes beneficial or does it aid in the cycling of these negative images? I think the distinction between acceptable depictions is hard to decipher, especially when the blurring of boundary lines is so present in comedy. ”Girlishness is a kind of femininity that is rarely extended to black women, a construction that makes vulnerability a privilege of the powerful.” Great point to bring up in regards to the representational history of assertive black women in the show; as social pressure doesn’t grant black women (and men) the same room for vulnerability.

So there I was desperately looking for articles in FlowTV that might have the slightest connection to Bill Moyers Journal (BMJ), when I found, believe it or not, this article by Jennifer Fuller.

You’re probably wondering what BMJ and Flavor of Love (FOL) could possibly have in common. On the surface, nothing; but in deeper respects, a great deal. Generically, both are host-driven “reality TV” programs, with BMJ exemplifying the old model of reality TV based on structured in-studio conversations between well-behaved elites ignoring the cameras and FOL exemplifying the newer reality TV model based on over-the-top location situations featuring hyper-active and far-from-harmonious celebrities and celebrity wannabees contesting for the camera’s attention.

I know you think I can’t be serious. After all, these two series are fundamentally different in shooting location, talent, aesthetic sensibilities, narrative pretenses, and their balance between reason and emotion, between words, images, and actions. Yeah, the reality TV genre sure has expanded, hasn’t it? But, you know, the two shows share more than a common genre. Both are, of course, eponymous, and more crucially, owe their existence to their host’s prior renown. I said earlier they are both host-driven, which implies a degree of host centrality far beyond simply saying they are hosted. In FOL, the supporting characters and contestants vie for Flav’s attention—and the degree to which they debase themselves in order to receive his blessing is one reason why Fuller felt compelled to justify her interest in the show by writing the FlowTV article. Moyers’ guests apparently do not feel a similar need to compete for his attention, but we should not underestimate Moyers’ power to direct their behavior as chief interrogator and provider of the media soapbox. They know that a good conversation may land them the opportunity to be invited back, while a bad one will likely foreclose that opportunity. They know, as well, that it is Moyers who does the asking and they who do the answering, and in a tone and with language that is calm, rational, and by all appearances, measured.

Some of you might suggest that BMJ is all about politics, and in its high points, FOL is all about race. But politics and race are not mutually-exclusive. In fact, Fuller’s larger point is to show how FOL and our reactions to it are deeply political and consequently surprisingly complex. As she says, “my goal wasn’t to suggest that Flavor of Love is politically ‘good.’ I wanted to show that it is politically complex…We should be mindful enough and brave enough to consider the cost of privileging the educated, middle class, chastely heterosexual flavor of blackness as the only ‘positive’ one, no matter who is watching.” Fuller was not referring to any show in particular, but for all practical purposes, she might well have named BMJ, whose guests uniformly represent privilege, whatever their race. So, if BMJ is not helping FOL to realize Stuart Hall’s ambition to end “the innocent notion of the essential black subject,” what is it doing? Perhaps something no less important than helping to realize the end of the “essential political subject.” Moyers is at his best when he puts aside political subjects and policy debates, and focuses on intensely personal subjects. Two recent demonstrations of this were his interviews with Parker Palmer about the latter’s battles with depression in the context of the nation’s own social woes, and with the African-American poet Nikki Giovanni about the stories behind her poems. Sure, Giovanni reinforces the notion of the essential positive black role model, but Moyers’ interview privileges and humanizes her in way that many of FOL’s women are never humanized or privileged. Race and politics are implicated in both series but, as Fuller points out, the story is much more complex.

Pingback: My thoughts on T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting’s “Pimps Up, Ho’s Down” « Feminist Music Geek

Pingback: Ella Fitzgerald and black girlishness « Feminist Music Geek