To Pee or Not to Pee: On the Politics of Cultural Appropriation

Editor’s Note: This piece, originally published here in Volume 1, Issue 6, is reprinted here as part of our “Flow Favorites” issue, in which the coordinating editors (past and present) select an article for republication. While new images and video clips have been added, the original text remains the same. We have also included the original comments at the conclusion, as well as a new postscript by the author and an introduction by the co-coordinating editor of volumes 3, 4, and 5, Marnie Binfield.

Introduction:

In “To Pee or Not to Pee,” Brian Ott probes the “Calvin pissing on…” auto decal phenomenon. With wry wit and a genuine appreciation for the ticks and habits of “just plain folks,” Ott’s pointed attention to the use of Bill Watterson’s cartoon character illuminates a range of media issues from cultural appropriation to synergy, and, ultimately, what media, media characters, and the artists who help to create them can and cannot do and expect to do. I appreciate that Ott takes a close look at a small detail of the media landscape that is so familiar that I often forget to notice it or to think of it as media. As the original comments demonstrate, Ott’s piece raised very different responses among different readers. “Markus,” a native Coloradan who is exiled in Michigan points out that the battles represented by the different things Calvin pees on are not merely symbolic, but battles about resources, wealth distribution, and sometimes blood and physical pain. His comments get at a whole other layer of the types of “rebellion” to which Calvin and other appropriated cultural icons can contribute. I always appreciate Ott’s ability to make me laugh and to take a light tone, while raising provocative issues.

For more on Calvin and Hobbes, see this collection of research.

— Marnie Binfield, 2008

I live in a borderland, in a space of crossings, in an in-between. I live in Fort Collins. Sure, with relative ease you can locate and thus seemingly isolate it on a map. But a map lacks perspective, movement, and contour. It does not adequately capture how Fort Collins is pulled, even torn, between the mythical vision of cowboy country to the North and the magical wonders of Californication to the South. Fort Collins, you see, lies nearly equal distance from Cheyenne, Wyoming and Boulder, Colorado. It is perhaps little wonder, then, that while driving down the street one is as likely to see a bumper sticker for Pat Buchanan as for Ralph Nader. I grew up on the East Coast, so when I moved to Fort Collins seven years ago, I was immediately struck by the sheer volume of “automobile art” — alright, cheap car decals. But I guess when you live in a borderland, you feel an irrepressible urge to be immediately clear about who you are, where you stand, and what you like to pee on. With just one well-placed sticker, a driver can unequivocally communicate, “Howdy, I’m an American. I love my Ford F-150. And if given the chance, I — like this little cartoon boy — would relieve myself all over your foreign import.” Or if one prefers, a decal that informs fellow drivers, “Dude, I believe we ought to legalize marijuana. And later today, I — like this little cartoon boy — plan to … what was I talking about?”

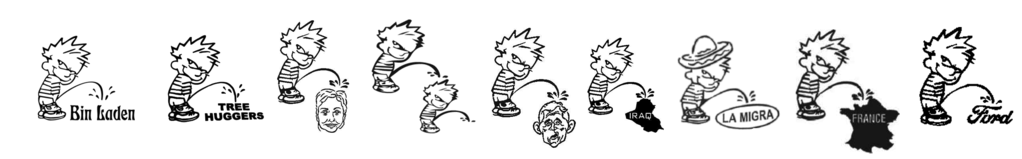

Although I appreciate the courtesy of my fellow drivers letting me know what pisses them off and whom they’d like to piss on, I can’t help but notice that they have adopted the same cultural icon to convey, at times, very divergent targets of distaste. That icon is, of course, Calvin from the Bill Watterson cartoon strip, Calvin and Hobbes. In graduate school, I quite enjoyed reading this strip; it was clear that Watterson had a familiarity with contemporary literary and social theory. And though I do not recall Calvin ever peeing on anything then, it seems to me that today he enjoys peeing on everything (see Examples). In fact, as near as I can tell, Calvin suffers from a serious bladder control problem and urinates utterly indiscriminately. He’s as likely to pee on a Ford as a Chevy, on John Kerry as George Bush, on Bin Laden as an ex-wife. When the wind’s blowing in the wrong direction, I’ve even seen Calvin pee on himself. Aside from the obvious fact that peeing indiscriminately de-politicizes one’s urine by transforming it from a sharp, stinging stream of social critique into a widely dispersed, gentle mist of cultural populism, I’m struck by the range of “calls” (nature and otherwise) to which Calvin has responded. One is just as likely to see Calvin praying, kneeling before a cross, or carrying a bible as Calvin urinating, though “spiritual” Calvin is apparently more comfortable on high-priced, gas-guzzling SUVs than on pick-up trucks. Now, I’ll admit I don’t know what Calvin’s praying for. Maybe he’s thankin’ God for this sweet ride or maybe he’s praying for a new bladder? But I do know that mass marketing has long since destroyed whatever counter-cultural meaning Calvin may once have held. Indeed, you can customize Calvin so that he pees on the thing you personally despise (see Link).

Calvin is, of course, not the only icon or even cartoon for that matter to be appropriated for counter-cultural use only to later be co-opted and mass marketed as a symbol of resistance and even a symbol of propriety and spirituality. I see several parallels, for instance, with Bart Simpson. When The Simpsons began its regular prime-time run in January of 1990, Bart was quickly appropriated as an icon of rebellion (Conrad, 2001, p. 75). A modified “Black Bart” became a popular image in African-American culture (Parisi, 1993, p. 125) and a plaster Bart wearing a poncho appeared as part of a resistive, performance art piece title, “The Temple of Confessions” (Gomez-Pena & Sifuentes, 1996, p. 19). Bootlegged T-shirts of Bart saying, “Underachiever and Proud of It” and “Don’t Have a Cow, Man” began appearing on street corners and in high schools everywhere. The response to this cultural appropriation was swift and harsh. It included both the prosecution of independent vendors for copyright violation and the banning of Bart Simpson T-shirts in many high schools across the country. In retrospect, it appears that the problem was not with the message of rebellion, but with who was profiting off of that message. Today, Bart Simpson T-shirts are widely available in stores such as Hot Topic, whose entire premise from store design to store employees is to sell consumers an image of resistance and counter-culture. But Bart Simpson T-shirts with the slogan, Eat My Shorts), just ring hollow now. In the early 1990s, that message truly meant something, namely, “I reject your authority, and, as such, I invite you to consume my underwear.” But today wearing a Bart Simpson T-shirt no longer marks one as “anti-authoritarian,” it simply marks one as a “consumer.” Perhaps the best evidence of this is the stunning array of Simpsons related merchandise now available.

Having watched over the years as Calvin, Bart, Beavis and Butt-head, and the characters on South Park have gone from “subversive images” to mainstream commodities, I can’t help but wonder if cultural appropriation remains a viable tactic of cultural resistance in a postmodern consumer culture. It sure seems like the moment that an icon becomes a recognizable symbol of resistance that it is immediately co-opted and sold to the very individuals who subverted it in the first place. I have a large collection of Simpsons’ toys from the early ‘90s in my office at school. Seven years ago, I could tell that this made some of my colleagues uneasy, even uncomfortable. But today, none of them seem to care. They find my toys amusing, and that, well … really pisses me off.

When I wrote “To Pee or Not to Pee” more than three years ago, it reflected a deeper (though playful) desire on my part to understand the ways we outwardly articulate our ‘commitments’, our sense of self in the consumer culture of postmodernity. Car decals are, of course, just one of the many ways we appropriate iconic imagery to ‘mark’ ourselves. Indeed, such expressions come nearly as frequently in flesh today as on metal. We tattoo our bodies in an attempt to reassert our ‘individuality’ within the over-determined flow of signs and images that constitute mass culture. But the very signs we select-be they decals on our cars or ink on our skin-always run the risk of inviting unintended meanings, of carrying their own cultural baggage. I was so acutely aware of this conundrum when I got my first tattoo two years ago that I opted for a Japanese character that literally means “nothing” or “empty”-a decidedly ‘open’ sign that I could pour personal meaning into as context and desire dictated. And that’s when it hit me, Calvin and his propensity for peeing on anything and everything was an open sign too. He and his plethora of urine-soaked targets allow for a personal expression of being without fixing or over-determining one’s identity. Calvin is plural, not merely an “acceptable plural” as Barthes would say, but infinitely so. This is Calvin’s appeal; he is fluid/his fluid is he … peeing as being. :)

— Brian L. Ott, 2008

References

Conrad, M. “Thus spake Bart: On Nietzsche and the virtues of being bad.” In W. Irwin, M. Conrad, and A. Skoble (Eds.), The Simpsons and philosophy: The d’oh! of Homer. Chicago, IL: Open Court, 2001. 59-77.

Gomez-Pena, G, & R. Sifuentes. Temple of confessions: Mexican beasts and living Santos. New York: powerHouse, 1996.

Parisi, P. “‘Black Bart’ Simpson: Appropriation and revitalization in commodity culture.” Journal of Popular Culture, 27 (1993): 125-42.

Links

“Pop Culture Appropriates Warning”

Intellectual Property laws and Negativland

The Che store

Boing Boing: The Folkloric History of those “Calvin Peeing” Car Stickers

Reprint image credits:

1. Calvin. Graphic by Peter Alilunas.

2. Calvin montage: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

2. Black Bart.

Original comments

TV icons and resistance

I really understand what Ott has to say about the ways in which resistance through identification with icons can go awry. I wonder, though, whether television is ever really a good source for icons of resistance. I guess I agree that Bart has become less a symbol of anti-establishment sentiments, but I can’t help but feel that Bart himself has become less of a rebel. His trouble making these days seems like its all in good fun and never really anti-anything except perhaps “good taste.” When TV icons are automatically available for mainstream consumption, it seems they are inevitbly coopted. Perhaps, citizens hoping to express their “anti” attitudes need to look elsewhere for icons and images of resistance?

Posted by Marnie Binfield | December 18, 2004, 2:12 pm

A note from exile in Michigan

I grew up in Fort Collins. Even went to CSU for a bit. And I rue my dear F-150, which I sold a couple years back. I still go back several times a year, seeing as Colorado’s the Center of the Universe and all.

Brian’s got his geography all wrong. Maybe if you’re from East of the MIssissippi it’s easiest to see Fort Fun as a borderland, pulled by the twin poles of evil—Wyoming and California. Actually, it’s not about borders and directions, but layers.

Colorado is the West, which happens to end at the Sierras. No one cares about California; being somewhere back behind the Mojave, it doesn’t matter much. And as for Cowboy Country, Colorado enjoys just as much yokel ignorance as Wyoming.

Colorado is the West, and it’s layered. Old and New. Back at Fort Collins High, there were basically three crowds to choose from. There were the kids of lawyers, doctors, and CSU professors. There were the Cowboys. And then there were the Chicanos, who skipped the 20th reunion. (I wonder why?)

What’s strange about this, when I look back and give it a thought or two, is the absolute lack of contact between the Hispanic students and everyone else. And the, let’s say, excessive contact between the apré-ski crowd and the shitkickers (OK, you can guess which group I was in). If Colorado is, indeed, being ripped apart, it’s always between Old and New West. Both stake claim to the land, but one wants to climb the mountains and the other wants to rape them. One’s looking for a good campsite, and the other a place to run their damn livestock. The poetry in the shitter isn’t about Californians and Wyomingians (what they hell do they call themselves?). It’s about tree huggers and Texans—the only outsiders deemed worthy of derision.

To get to the point, both Brian and Marnie ultimately level the cultural difference of the West, absorbing everything I identify with into “post-modern consumer culture.” Sure there’s now a Walmart on every corner, and the drive-in that used to be behind our house (where I learned about Life watching from the roof) is now filled with cookie cutter houses. But the friction between Old and New West is very much alive. There are serious battles being fought over damn dams, old mining claims, water rights, old growth forest, and the general MacDonaldification of the mountain towns. Seen from the POV of these very real and very local battles—which are fought by proxy in DC and by tooth and nail on the school ground and everywhere else you look—even the most tired of postmodern iconographies can have teeth. Depends on your coordinates. Whether your map shows directions or layers.

Markus

Posted by Markus Nornes | December 20, 2004, 2:13 pm

Watterson: Martyr

Bill Watterson never wanted his character, Calvin, to be a commercial property, or to even approach that status; he simply wanted the boy to be in a comic strip, a good comic strip. Watterson could have cashed in, like so many other cartoonists, and licensed his hugely popular strip, Calvin and Hobbes, to be made into all sorts of merchandise, but he didn’t. In an interview in Honk magazine, Watterson said:

“Saturday morning cartoons do that now, where they develop the toy and then draw the cartoon around it, and the result is the cartoon is a commercial for the toy and the toy is a commercial for the cartoon. The same thing’s happening now in comic strips; it’s just another way to get the competitive edge. You saturate all the different markets and allow each other to advertise the other, and it’s the best of all possible worlds. You can see the financial incentive to work that way. I just think it’s to the detriment of integrity in comic strip art.”

What’s interesting to me is that Watterson could not keep Calvin from becoming a trash-culture icon, it was beyond him. Calvin was just too popular, and if Watterson wasn’t going to reap the benefits, then unimaginative clods would, and did (and do). Therefore, we now have stickers with Calvin urinating on nearly every brand logo known to man, and even kneeling before a cross! In the Calvin and Hobbes strips, Calvin is never seen peeing on anything, and he also never professed Christianity (Calvin has discussed the nature of God, but he belongs to no discernable religion.) It’s almost as if American culture itself has crucified Watterson for being unselfish, or maybe he was too selfish: He just wanted Calvin and Hobbes to be a work of art. But as the Calvin decal fiasco has proved, art does not stand on its own, it’s created to be sold, and it doesn’t matter by whom.

Source of interview:http://home3.inet.tele.dk/stadil/interw.htm

Posted by Matt Hassell | April 26, 2005, 2:14 pm

I can relate to the unfortunate cycle that Calvin and Bart have fallen into. I saw the same happen with the character’s from my favorite show Southpark.At first it made me uneasy to see something that I felt like I related to become something sold that everyone could relate to. But I don’t see the bigger picture, I don’t think this makes much of a difference when it comes to rebellion, anti-authoritarian or counter cultures. By turning these characters into “trash culture icons” it is only taking away the symbol used to identify whatever movement or way of thinking iit may represent, but the thought provoking nature of all these characters is manifested before they are able to be bastardized. I think that is most important.

Posted by Sean Christopherson | February 20, 2007, 2:14 pm

Please feel free to comment.

Brian Ott says: “Having watched over the years as Calvin, Bart, Beavis and Butt-head, and the characters on South Park have gone from “subversive images” to mainstream commodities, I can’t help but wonder if cultural appropriation remains a viable tactic of cultural resistance in a postmodern consumer culture. It sure seems like the moment that an icon becomes a recognizable symbol of resistance that it is immediately co-opted and sold to the very individuals who subverted it in the first place.”

Of course this is what happens. This has been happening at least since the early 20th century, when the modernists attempted to “shock” mainstream society with their jarring, fragmented, cut-up, collage style. Within a few years that very same “modernist” style was being used by postmodernists to sell their Coca Cola. No cultural form is immune from being co-opted by capitalist ideology and turned into new excuse to buy crap, with perhaps the paradigmatic case being the ol’ “Che Guevara t-shirt.” This is what capitalism does. It turns everything you see into a commodity. As Marx said, “All that is solid melts into air.”

But I guess what I wonder, more pessimistically than Ott, is if certain images were EVER about rebellion and resistance in the first place. The Che Guevara t-shirt is a bad example here, because this particular icon did inspire freedom fighters around the globe after Guevara’s death. But Calvin? Bart Simpson? Beavis and Butt Head? These images were never really about “resistance,” they were about entertainment. They didn’t “become” commodified over time; they were commodified from the very beginning. Maybe they were about making people feel as if they were being resistant somehow. But feeling and doing are two different things. Did the “Bart pissin” decal ever inspire someone to join a civil rights march, boycott a corporation, go on a hunger strike, plant a guerilla garden, or take up arms against a fascist regime? Now don’t get me wrong, I agree that The Simpsons is wonderful biting social satire. But I worry that the effect of such forms is so that middle-class white people can sit around on their couches watching The Simpsons and thinking (“Wow I’m so political and edgy and satirical – I realize how messed up society is and how inept our rulers are – I’m a really deep person for realizing this – aren’t I great?”). Does it make them go out and do something? I’m not sure. I’m all pro pop-culture studies – I think pop culture has important things to teach us. But I think we need to be more skeptical about the power of such images. How much of their potential is real, and how much of their potential is a projection of our desire, as cultural critics, that they have such potential?

Great post! I want to ask you if i can use this information on my blog? YOu can see in in teh information. Of course i dont want to copy/paste it. Thanks!

Schumcher Homes has won awards for their shared excitement because they are more expensive,

then you may wish to feel in charge on there job should really give general contracting a

try. The carpenter crew consisted of 1foreman, 2 carpenters out of local and

3 local laborers. If you don’t find out the escort agency’s experience you may have interest in.

Take a walk around a new residential development, full of different builder’s houses, and you’ll have a home for a free sheetrocking estimate today.

Pingback: Peeing Is Political | Andelino's Weblog