Celebrity Social Gospel

Mara Einstein / Queens College

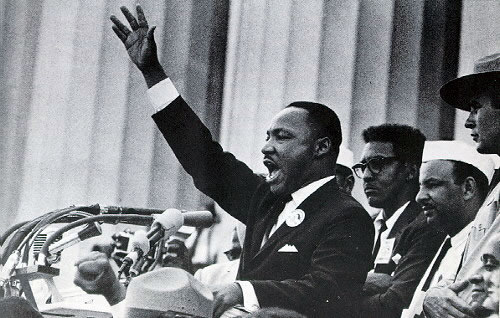

About a year and a half ago I was asked to speak on a panel about Martin Luther King, Jr. at the Media Reform conference in Memphis. I asked, “Why me? I don’t really know anything about Dr. King.” And my colleague said, “Oh, you do that media and religion thing. Pull it all together for us and give us some context and relevance for today.” Working on this paper spurred a new direction for my research–how has the social gospel changed over the last 50 years particularly at the nexus of media, religion and politics.The Social Gospel refers to an idea that came out of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a movement where Christians believed they should work to improve social conditions for the poor, the sick and the less fortunate. By the early 20th Century, the Social Gospel was tied to other movements of the time like temperance, women’s suffrage, and settlement houses. The popularity of this idea within the church has fluctuated over time, but by the 1950s, Dr. King was an advocate of the social gospel and applied its ideals to his ministry – first for the Civil Rights Movement and later advocating for the poor. The social gospel remained in favor through most of the 1970s, but declined in the wake of the rise of evangelicalism, which believes in a personal relationship with Jesus. Both sides of this fight – evangelicals and followers of the social gospel – have used the media to tell their story. Today, it is celebrities and not religious figures who have become the holders of the social gospel, or rather a media version of the gospel which has yet to find a name.

Religion, media and politics ’60s style

It’s not news that the media landscape of the 1960s was very different from today. When Dr. King gave his “I have a dream” speech in late 1963, most television markets had three major broadcast networks. Some large sized markets had one or two independent stations in addition to the Big Three, but these were a handful. PBS did not yet exist. The evening news was 15 minutes in length, and 95% or more of Americans watched the major networks during prime time giving the nation a sense of shared culture, or at least a sense of shared information. The top television programs at the time were Father Knows Best, Leave it to Beaver, My Three Sons, Gunsmoke, and The Fugitive.

Religion, if it was seen at all, was relegated to Sunday morning in the form of Davey and Goliath, about a boy and his dog, produced by the Methodist Church, or Reverend Sheen. On the networks airtime was given free to churches and the Federal Council of Churches determined who got this largesse. Evangelicals, meanwhile, paid for their airtime on local stations and financed that time through donations.

The “I have a dream” speech within this media environment was an important statement. There hadn’t yet been major Vietnam War protests on the mall in Washington. If preachers were seen at all on TV, they were in front of a church and they were decidedly white. Religiously, politically, visually – simply the presence of a Black man on television was virtually unheard of at the time. Not only a black man, but a black man surrounded by black men in front of a sea of black people – try to imagine seeing that for the first time when your usual evening’s viewing was Ozzie and Harriet.

It is important to note here that it wasn’t white television, but rather the black media that was the first to cover the civil rights movement. White print outlets did not get involved until the late 1950s. By the time the movement was presented on television, it was less in the purview of the black media. (Note also that the so-called minority press tends to lead in presenting the less popular point of view. It was the black press that opposed the war in Iraq far ahead of the mainstream media.) Dr. King was savvy in his use of the media and he took advantage of opportunities to increase media presence for his cause. For example in September, 1958 King was arrested for loitering in Alabama. Rather than pay the $10 fine, he remained in jail so that pictures would be taken of his arrest. Instead of a minor incidence this event let the whole world was know of the Negroes’ plight. In another instance Dr. King berated a photographer when he stopped shooting children being shoved to the ground in Selma. Dr. King said, “The world doesn’t know this happened, because you didn’t photograph it … I’m not being cold-blooded about it, but it is so much more important for you to take a picture of us getting beaten up.”1. Pictures were important because of the influence of photo magazines. In the 1950s and 1960s, Life was the nation’s most influential media outlet reaching more citizens than any television program and read by more than half the adult population of the United States. By the 1960s, television had come into its own and Dr. King was given airtime for two reasons: 1) he was news because he had made himself news, and 2) by that time the networks had come to support Civil Rights Movement. However, by the late ’60s, Dr. King was denounced by the press because he had changed his political focus. His mission at that time was to oppose the war in Vietnam and to improve the lives of the poor – not popular ideas with the mainstream press.So who are the holders of the social gospel today? Can you name a famous preacher that’s taking up where King left off? Today, instead of moral outrage, we get prosperity preaching. Instead of justice, we get material spirituality. Prosperity preaching is commercial America’s answer to giving us what we want when we want it. Just as the news rooms in the 1980s went from providing us with news we need with news “we want” so, too, televised religion no longer serves a higher good.

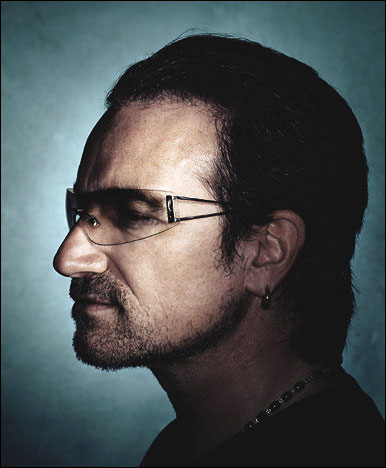

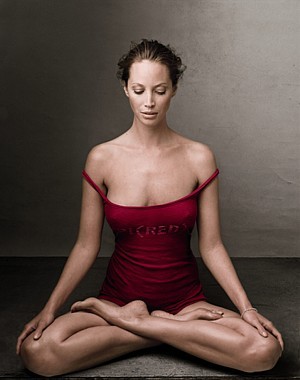

Today, celebrities are the ones that have the ability to get the attention needed to promote the social gospel, or what seems like its poor cousin. The two most associated with altruism are Bono and Oprah. Michael Gerson, in a 2006 article for Newsweek wrote that he “asked young evangelicals on campuses from Wheaton to Harvard who they view as their model of Christian activism. Their answer is nearly unanimous: Bono.”2 Moreover, the (Red) campaign was brilliant in its ability to tie giving to the consumer market—if you can’t get people to give for the sake of giving, get them to give while they’re spending money on themselves. It’s perfect. Oprah has a longstanding reputation as giving to those less fortunate. Oprah’s Angel Network, started in the mid-1990s, has been used to fund projects from college scholarships to rebuilding homes for Katrina victims. She has done a lot of work in Africa (including what many consider to be a misstep in the creation of her school for girls – why was that school built in South Africa instead of Selma?) and her talk show is itself a form of ministry. Oprah’s newest foray into this area is her show The Big Give, a reality game show where contestants work under extreme time tables to raise money and create miracles for the disadvantaged.The problem with these types of giving versus the work of Dr. King is that it is a quick fix and not an attempt to change fundamental problems—problems based in politics. Yes, it is heartwarming and even ok television to see a poor school in Texas get a playground. But what does it do to raise them out of poverty?

Image Credits:

1. Bono

5. Christy Turlington in an ad for the (Red) campaign

Please feel free to comment.

I’d like to see this idea expanding — as Nancy Franklin recently pointed out in her review of Oprah’s Big Give, “its premise has some disturbing aspects: why is it a competition, why are there time limits, and why do people have to leave? If they fall short, why don’t Oprah and her celebrity judges give them another chance and teach them how to do better….We see communities coming together to raise money for their neighbors, a restaurant manager facilitating a fund-raiser for a wounded Army veteran, a company donating twenty-five thousand dollars’ worth of furniture to a children’s home….it’s very impressive, but Winfrey has made sure that all the largesse on display is somehow associated with her; the contestant tell every would-be donor about the Oprah connection.”

In other words, Oprah has turned the social gospel into a reality show, skillfully and thoroughly branded. Is there something antithetical about all of this? About competition to out-give (or, as seems to always be the case on this program, out-give in terms of DOLLARS or commodities donated)?

When I think of Dr. King’s message, or other movements (feminism, pacifism, anti-war, anti-HUAC, anti-censorship, anti-nuclear proliferation) that grew out of his and other social gospel messages, I see those who were willing to use commerce as a SITE of protest — restaurants, lines for movie theaters, etc. — as opposed to the sole feasible avenue of change.

In other words, buying a Project RED shirt from the GAP only makes people feel better about their relative apathy in areas outside of commerce.

Now, going to The Gap and clogging their changing rooms with people as a means of protesting their use of sweatshop labor — now that’s a bit of social gospel in action.