The 2008 Academy Awards… and the Evil Just Outside the Frame

Editor’s note: the 2008 Academy Awards were held on February 24th, 2008. No Country for Old Men, directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, won Best Picture and three other Oscars. A complete list of winners is available here.

All serious thinking about art must begin from the recognition of two apparently contradictory facts: that an important work is always, in an irreducible sense, individual; and yet that there are authentic communities of works of art…It is to explore this essential relationship that I use the term “structure of feeling.”1

(Raymond Williams, Drama from Ibsen to Brecht, 1969)

States like these and their terrorist allies, constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world. By seeking weapons of mass destruction, these regimes pose a grave and growing danger…and the price of indifference would be catastrophic.

(George W. Bush, State of the Union Address, January 29, 2002)

I don’t want to push my chips forward and go out and meet something I don’t understand. To go into something you don’t understand you would have to be crazy, or ‘become part of it.’

(Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, played by Tommy Lee Jones, No Country for Old Men)

[youtube]http://youtube.com/watch?v=AVYdSre21bU[/youtube]

“The Evil Outside the Frame” (1:00), edited by Bernard Timberg and Michael Dixon.

During the Christmas holidays of 2007-08 I tried to catch up on a number of films I had read or heard about: No Country for Old Men, Into the Wild, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Michael Clayton, There Will Be Blood, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Charlie Wilson’s War, Atonement. Something struck me about these films, an undercurrent, a persistent dark theme they seemed to share. This theme lurked in words of their titles: “No Country… Devil… Dead… Wild… Blood… Assassination… War… Atonement.”

In each of these films protagonists would come into contact with forces of evil and struggle against them, but as often as not the evil was still out there at the end of the film. I was not seeing the traditional Hollywood endings that John Cawelti calls “moral fantasies” in which audiences leave the theater satisfied that the right conclusion had been reached.2

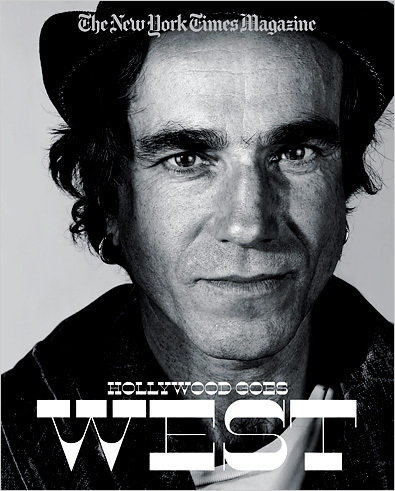

And then there was the fact that there were so many Westerns appearing this year—almost half of the films listed above were Westerns—with two of them, No Country for Old Men and There Will Be Blood, leading contenders for Academy Awards when the nominations came out in January 2008.3 Two months earlier The New York Times Magazine devoted an entire issue to the re-birth of the Western, noting that the Western is often our modern American morality play.4

No Country for Old Men won Best Picture (Scott Rudin, Joel Coen, Ethan Coen, producers), Best Director (Joel and Ethan Coen), Best Adapted Screenplay (Joel and Ethan Coen), Best Supporting Actor (Javier Bardem), and was nominated in four other categories.

The paradigmatic film, and the winner of Best Picture in the 2008 Academy Awards, was No Country for Old Men. In No Country the evil was greater than any man, any law enforcement concern, any human agency. The cold, methodical killer played by Javier Bardem was, from the beginning, a force of nature. The efforts of the sheriff (Tommy Lee Jones) to track this force of nature down, contain it, and bring it to justice were, as he and we increasingly come to understand, futile.

This film expressed in starkest terms the force and staying power of evil. Though all Westerns represent a form of entrenched dualism, the struggle between good and evil, how that struggle plays out changes over time. In the classic Western, the frontiersman mediates between the untamed forces of the wilderness, on the one hand, and the necessary and ultimately overpowering mandates for peace, justice and civilization on the other.5 This is how the West is won.

But at times, and in certain historical periods, the drama between good and evil is not so clear cut. In the “professional” plots of the Western of the 1970s, film historian Will Wright sees films like The Wild Bunch, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and The Professionals launching a new plot that focuses on teams of professional heroes and anti-heroes who populate the West.6 Wright’s book was completed before films like Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992), which paved the way to the post-Western Westerns discussed in this piece. These were Viet Nam era films in which audiences were left to question how good was the good, how evil the evil, and the range of “grays” in between. Still, by the end of the film, some kind of order is re-established. These are, after all, “rites of order” as Thomas Schatz puts it, rites of contested space, and someone must remain in control of the space at the end.7 But now No Country for Old Men moves past the professional plot described by Wright. At the end of this film, as the lights come up and the audience files out, there is no ambiguity, no gray between black and white, no partial solutions. Evil rules. It has no contenders. It hovers, triumphant, over the last frame.

No Country for Old Men is a stark variant of the “evil is out there” theme, but other films reflect it as well. Into the Wild, for example, is a combination road picture, social critique, psychodrama and survival story. There is no single psychopathic killer to confront, as in No Country, but the protagonist is finally overcome by the implacable force of nature itself, the audience looking on in horror. Similarly, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead begins as a caper film but moves into a very different kind of dark space. The devil here is truly in the details. The temptation of going after easy money is quickly subsumed by the malignant force of destiny itself. Once again, as in No Country and Into the Wild, a deadly vortex of circumstances moves forward, and, once in motion no human will or act can stop it. The ending of this film too is devoid of redemption.

There Will Be Blood won Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis), Best Cinematography (Robert Elswit), and was nominated in six other categories.

And then we have There Will Be Blood. It runs its course through black surges of blood and oil to its own predetermined end of death, dismemberment, and oblivion. In the tradition of Citizen Kane and Godfather 2, among others, it is a story of hubris and power that ultimately feeds on itself, while along the way simple moral folk are destroyed. The son of the oil tycoon does escape at the end as some kind of balanced, moral man—just barely. Hanging over the final scene of the film, in the bleak ending of Blood, the evil once again remains, this time disintegrating into madness. The only solution, as the son finds out, is to retreat or escape from it entirely.

We see it this year even in films that seem to fulfill the requirements of the uplifting “moral fantasies” of Hollywood. Somehow even these films leave an aftertaste, a question, something viewers must ponder or deal with when the lights come up. Charlie Wilson’s War, Atonement, and Michael Clayton all follow this pattern. They confront substantial evils in the course of their narratives, and seem to overcome them, but unstitched plot lines or penultimate codas disturb the equilibrium of their endings. In Charlie Wilson’s War the victory of the U.S. against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan is subverted by the final scenes in the film and our own awareness of history. Atonement, a romance and an upper-class melodrama set in World War II England, appears to celebrate a romantic passion that succeeds over all who would deny it. But the film’s harder message is that the lives of the principal characters have truly been destroyed—early on and before the romance has ever really had a chance to come to fruition. In fact, the evil that represents the pivot point in the plot has gone unpunished, has been normalized even, in the character of a war profiteer and his accomplice. In both Charlie Wilson’s War and Atonement, despite seemingly satisfying conclusions, the evil is still out there.

Michael Clayton won Best Supporting Actress (Tilda Swinton) and was nominated in six other categories.

Along with No Country for Old Men, There Will Be Blood, and Atonement, the film Michael Clayton was a Best Picture nominee. The morally complicit character played by George Clooney seems to triumph over the forces of evil at the end. At the last minute he exposes, through a Watergate-like investigation, the insidious cover-up of the powerful law firm for which he has been working. But the ending is not triumphant. Quiet, exhausted, the Clooney character simply walks away. He has done the right thing but is still defined by the moral compromises that have marked his failed personal life and career as the firm’s fixer. It seems likely that the powerful institutions he has worked for will remain as fixed and as powerful as ever.

What do all these “evil is out there” endings signify?

Taken together they represent what Raymond Fielding aptly terms “the structure of feeling” of an age.8 This structure of feeling arises from “social crises, technological developments, and new patterns of experience” that “lead to the establishment of new conventions” in drama or art, as alterations of accepted standards of aesthetic performance become inscribed in the film and literary “documents” of their time.9 During the era of cultural conflict, uncertainty and the Vietnam war, for example, Peter Biskind points out how many of the films of the late 1960s and 70s “dared to end unhappily”: Midnight Cowboy, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Easy Rider, Raging Bull, and The Shootist, to name a few.10

If we accept that the open ended or morally ambiguous conclusions of these films represent a “structure of feeling” in Williams’ sense of the term,11 and that the “evil out there” has a social as well as aesthetic foundation, I would suggest that we are now entering an era where our social experience of the Iraq war is reflected in our film experience in much the same way that it surfaced during the Viet Nam era.

Even as the battle against worldwide communism has waned, we live once again in an era when our President has taken action against what he calls the “axis of evil.” Soldiers and commentators once again invoke a “good guys”/“bad guys” formula. Despite the mid-term elections of fall 2006, where a clear majority voted for a Democratic Congress and an end to the war in Iraq, the war keeps moving forward. For myself and many others, it appears that no matter what–the elections, the popular vote, the mood of the country or the popular will–the Iraq war and occupation grind inexorably on. Though direct depictions of the war in Iraq have not done well at the box office, the structure of feeling embodied in the endings of these films does seem to represent our current social and political malaise.

Once again in the spring of 2008 we seem to be enmeshed in a time and a place where the evil is still out there with no easy or magical solution to it. Perhaps that is why Barack Obama’s call for change during the political season that parallels the Academy Awards is so galvanizing for so many. It is a vision of a way out of the dark mood of stalemate these films evoke.

Image Credits:

1. Daniel Day-Lewis

2. No Country for Old Men

3. There Will Be Blood

4. Michael Clayton

Please feel free to comment.

- Raymond Williams, Drama from Ibsen to Brecht, New York: Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 16-17. [↩]

- John Cawelti, Adventure, Mystery and Romance, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976. [↩]

- Both of these films, leading contenders for Best Picture, were shot at the same time in the same place, Marfa, Texas, as the press noted. Scott Bowles, “Hollywood deep in the heart of Texas,” USA Today, February 18, 2008, pp. D 1-2. [↩]

- “Hollywood Goes West” theme issue, The New York Times Magazine, November 11, 2007. See in particular A.O. Scott’s overview essay, “How the Western Was Won,” pp. 55-58. [↩]

- See, for an extended historical discussion of this mediated dualism, Richard Slotkin’s Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860, Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1973. [↩]

- Will Wright, Six Guns and Society: A Structural Study of the Western, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975. [↩]

- Thomas Schatz, Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking and the Hollywood System, New York: McGraw Hill, 1981. [↩]

- Raymond Williams, Preface to Film, London: Film Drama Limited, 1954; Culture and Society 1780-1950, Harmondsworth, Penguin, (1961) 1988; Drama from Ibsen to Brecht, Harmondsworth: Penguin, (1968) 1973. [↩]

- John Eldridge and Lizzie Eldridge, Raymond Williams: Making Connections, London: Routledge, 1994, p. 116. [↩]

- Peter Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood, New York: Simon Schuster, 1999, p. 17. [↩]

- It should be noted that a number of social critics have done extensive examinations of literature, film, and theater within the “structure of feeling” of their times. John Cawelti’s Adventure, Mystery, and Romance is one example (cited above). Other notable examples: Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler, Princeton University Press, 1966, and John Shelton Lawrence and Robert Jewett’s The Myth of the American Superhero, Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. [↩]

Well done. I enjoyed–and took heart from–the progressive reading of these films and the structures of feeling they embody. But what happens if we read them the other way, as signs of regressive politics? This was the feeling I was left with after seeing _No Country for Old Men_. If evil is a force of nature, rather than the result of human actions, then there is not much that humans can do about evil. This seems like a very conservative argument, rooted in Judeo-Christian ideas about the naturalness of moral absolutes.

While this is certainly an optimistic political season for progressives, with even the Christian Right re-tooling some of its rhetoric, those who believe in George Bush’s “axis of evil” have not entirely given up the fight. I wonder if these films don’t affirm conservative ideas about the naturalness of evil, even as they express frustration with the interminable Iraq war.

Nicely put together. Trying to see the air we breathe.

Interesting that these films, which share some of the properties you identify, are also, in sum, one of the best , most engaging, intelligent, and entertaining years for American film in a long time.

Nice read!

I wonder how moral we are supposed to read HW Plainview, given that he is going to Mexico–a new frontier–to continue the exploitative work of oil drilling.

Right as the US invaded Iraq, Hollywood produced a glut of historical epics, all celebrating the lone male [frontier] hero and all basically glossing over the violence wrought in the name of Western progress for the sake of celebrating Western progress.

2007, and those celebrations ring false. And post-Fahrenheit 9/11, major studios feel safe enough to dramatize the issues you raise.

Now I have some catching up on viewing to do!

Nicely reasoned argument. I have counseled colleagues and students alike the the current state of post-classical Westerns such as No Country and Blood are not dealing with new themes. Tom Schatz says that genre pictures “continually renegotiate the tenets of American ideology.” The Western according to Schatz is a genre of order as opposed to integration. Therefore, I’m curious why these films are what Cawelti describes as the structure of feeling on a national/individual level and not what Kracauer cites as the zeitgeist for German Expressionism films? My students recognize that nationalist cinematic products reflect nationalist sentiments from German Expressionism to Russian Formalism to French New Wave to Italian Neorealism and so on. That said, while Timberg’s piece here is well written and reasoned, I’m not sure it’s saying anything new, but rather recontextualizing current trends that have been present in cinema for more than 7 decades.