Where Babies Really Come From…

In the run-up to our son’s birth, my wife and I watched dozens of hours of TLC’s A Baby Story. Apparently, we weren’t alone: A Baby Story has ranked among the top-rated original daytime cable series among women 18-34 since 1999. It is particularly appealing to the nation’s wealthiest young parents. It has twice won a daytime Emmy. Anecdotally, every first time parent I’ve talked to has watched at least a couple of episodes. A Baby Story, it would seem, has become a present-day ritual for at least some segments of the expectant-parent population in the U.S.

The show is also highly economical, making it appealing to a shoestring cable network like TLC. Part of that frugality stems from the formulaic narrative structure, which allows efficient shooting and editing of a wide variety of personal experiences into a preset storyline: in the first half of each episode, we meet the expectant parents and hear why they want a child; in the second half, we witness the labor and birth; and in a final coda we return to the family several weeks later and are formally “introduced” to the newborn.

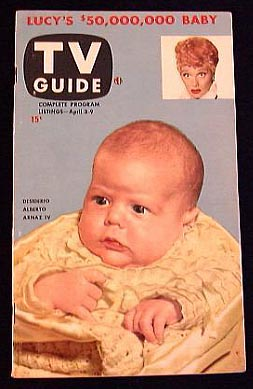

Perhaps the most remarked-upon feature of A Baby Story is its unedited footage of childbirth-what Salon.com TV critic Joyce Millman calls the “mommy shot.” Such footage is rare in television history. As a kid, whenever I saw a portrayal of birth on TV, my mother, a nurse and Lamaze teacher, would inevitably scoff at its over-sanitization and the use of a well-scrubbed baby who was several weeks old. None of that on A Baby Story: we see blood, screaming, squirming, bawling-everything except a straight-on shot of the mother’s vagina, which is digitally blurred during post-production. As noteworthy as these portrayals are, however, they are marshaled for specific textual and cultural ends.

Superficially, A Baby Story engages in a celebration of diverse women choosing among a diversity of ways to give birth: home births, water births, natural births, C-sections, surrogates, African Americans, Latinas, Indian immigrants, single women, Catholics, Jews, Mormons, and Wiccans all appear. Beneath this veneer, however, we see a subtle reinforcement of the medical establishment’s mantra that all labors must unfold in the same manner, that bodies that labor differently require intervention. At least part of the reason that this medical narrative dominates is that hospital births, full of medical intervention, have drama; they make for good TV. While medical interventions and the narrative of proper childbirth that underwrites them have dramatically reduced the mortality rate among mothers and babies, they also lead to excessive rates of Caesarean-section deliveries and epidural anesthesia.

My intent is not to advocate for or against any types of childbirth. Nor do I want to diminish the pain and fear that can surround birth and lead women to seek painkillers, doctors, hospitals, etc. But I do want to examine how the medicalized version of birth gets normalized by A Baby Story, despite its apparent celebration of diversity.

Birth narratives are important. Research has shown that women clearly remember the details of childbirth decades later, and that they attribute a good deal of their self-esteem to how they handled giving birth (Simkin, 1991). Midwives often insist that women who have negative memories of childbirth are more prone to postpartum depression (England and Horowitz, 1998).

A Baby Story tends to rob women of agency over their own births by portraying them as protagonists and their bodies as antagonists-a structure that also champions the medical establishment’s narrative: laboring bodies that “fail to progress” require medical intervention to “get the ball rolling” once again. Thus, regardless of the diverse circumstances and birth plans we encounter in the first half of and episode, the birth stories in the second half are almost always the same: women come to the hospital and either make good progress or don’t; those who don’t undergo intervention after intervention, typically without protest or discussion. The doctor simply explains to the camera that the mother requires this or that procedure. Never do we see discussions about whether the intervention is necessary at the given moment or whether non-medical alternatives (walking, warm bath, nipple stimulation) might also work.

By book-ending the birthing scenes with scenes of birth preparation and aftermath, A Baby Story takes the focus off of the mother and childbirth, recentering it instead on the excitement, joy, and challenges of childrearing. The soundtrack of episodes underscores this emphasis, with breezy piano music playing during the hopeful moments of the preparatory scenes, which returns during the coda. Birth scenes, by contrast, use only ambient sounds and a foreboding soundtrack. The foreshadowing of these early scenes is thus fulfilled by the joys of the coda, while the birthing scenes provide the narrative tension in each episode. Consequently, the woman’s body-at least in difficult births-becomes the primary antagonist that threatens the realization of parental joy.

Every episode features interviews with caregivers, partners, and family members during the birth. The women themselves are never interviewed, as they are otherwise occupied. While producers could return to interview mothers a few days later and insert those interviews into the birthing scenes, such a practice would increase the series’ tightly controlled budget. Likewise, mothers could be interviewed immediately after birth, but it seems unlikely that many women would be much interested.

Even the rare episodes that feature home births work to deny women control over the narratives of their births. The central narrative enigma in such episodes revolves around how well the mother will withstand the pain, and we witness several scenes of excruciating pain. Thus, the laboring body again becomes the primary antagonist, battling against the mother’s desire for a natural experience. This narrative of the mother’s relationship to her laboring body is at odds with non-medical portrayals that emphasize her agency and the embracing of, and working through, pain.

While episodes of A Baby Story may reinforce a medicalized narrative about birth, the consequences of such portrayals for viewers are almost certainly more complex. In our case, these stories prompted my wife and me to discuss her birth plan. Specifically, she saw one episode in which a woman waited until she was nearly in transition before she went to the hospital, and she found this appealing. The portrayal of various interventions led us to research their benefits and dangers, as well as alternatives to procedures we found ghastly.

The great benefit of A Baby Story, in my estimation, then, is that it does offer narratives of childbirth, even if those narratives tend to provide little useful information and reinforce hospital birth and medical intervention. Narratives of other women’s birthing experiences, even in such a commercialized and restricted environment, can allow viewers to reflect on their own plans, preferences, and experiences. Fortunately, other resources offering different narratives are available on-line and in libraries-accounts that validate something other than the medical establishment. Still, the narratives of A Baby Story are a significant change from the pain-free, worry-free, blood-free stories of birth that mainstream television has told for decades.

References

England, Pam and Rob Horowitz. Birthing from Within: An Extra-Ordinary Guide to Childbirth Preparation. Partera Press: 1998.

Simkin, Penny. “Just Another Day in a Woman’s Life? Women’s Long-Term Perceptions of Their First Birth Experience. Part I.” Birth 18, 4 (1991): 203-210.

Image Credits:

1. TLC’s A Baby Story

2. First TV Guide, 1953

3. Rachel and her newborn

4. Tim and Rita’s New Arrival

Please feel free to comment.

I found this piece fascinating — as a former nanny with no children of my own, I basically lived the “Baby Story” existence — most of the good, cuddly, warm stuff, but only from 9-5 each day. No middle-of-the-night wake ups; no birth; no breastfeeding. Just walks and naps and bottles. I know very few people my age (twenties and unmarried) who watch TLC and A Baby Story with any sort of regularity, but they DO watch A Wedding Story from time to time — a whole different type of alienation and sanitation of the experience of marriage. With all of these TLC productions, I wonder what’s at stake for portraying these events as such — I suppose very few people would want to watch a mother as she grapples with post-partum depression, but I do think that that sort of depiction could be quite comforting to other women grappling with the same emotions (e.g. Brooke Shields’ book). In other words, just because it’s not perfect doesn’t mean it won’t sell…..

Granted, you point out how much more expensive and obtrusive it would be for TLC to back and interview the mothers after the birth, so economic variables might prevent such “full” coverage, but what about “A Post-Birth Story”? Is there such a thing? Or maybe a “Frazzled Mother” story?

A really interesting piece on how television now offers narratives of our lives’ most intimate moments. I watched many, many episodes of A Baby Story while on restricted activity awaiting the birth of my twin daughters, during the many endless hours of nursing them in the year after their birth, and then again with the birth of my third daughter 4 years later. (In fact, i’d also watched A Wedding Story in the years before).

I confess to finding the neat narrative very compelling, and allowed me to reflect upon my excitement and fear about the impending birth, and then to remember and savour the details of the births afterwards. Even though I recognized the way the camera-work, editing and production parameters dictated and constrained the way stories were told, I still got teary-eyed each time the TV baby was born. I can chalk this up to hormones, but I think it’s also about the powerful connection it makes for the new mother. There were only so many times my family, friends (and even my husband) wanted to hear about my birth experiences, and this show gave me a conduit for remembering them.

As a cultural studies scholar and a video production teacher, I often felt conflicted about how easily i was manipulated by the stories and pat summaries of compelx issues, but part of the pleasure was surrendering myself to the story and suspending my critical eye. It is interesting to me that I could only do this for so long, however. A couple of months after each birth, A Baby Story stopped interesting me.

A final note: my twin daughters are now 8 and a half, and they like to watch A Baby Story. Although I am concerned about some of the messages the show gives about the birthing process (which Tim discusses so eloquently), I am reassured by the knowledge that each birth ends with a live, healthy baby. It gives them a relatively safe, relatively realistic version of North American childbirth (compared to what they’ll see elsewhere on TV), which is about as much as they need to see in living colour at 8 years old. I also use it as a platform to discuss alternatives to the hospital birthing process (their dad was born at home), midwives and more, and why so little attention is paid to what happens once baby comes home…

Great article! I had the great fortune of attending a friend’s birth while I was 4 months pregnant. Afterwards, it was impossible for me to watch the medicalized televisual products of birth. They enraged me. I could see the other members of my birth class getting manipulated by these texts and would recall the very questionable “options” my friend was offered during her labor and delivery. I dropped out of the course, and stopped watching Baby Story and other assorted stuff. What did I end up using in its place? Bradley Method books and Xena! When I did give birth, it was at UCSF, a teaching birth center where most of the MDs in training had NEVER seen a natural birth. My first child’s birth was in a lecture. Hottentot history aside, I think my desire to become a warrior woman from having seen an actual birth and on the other side, the drive to rely on the televisual in this our most intimate human moment stems from substituting mediated interaction for actual interaction and information. Yes, these shows are informative, if you know how to then go look for further info. And even if you do, maybe you really sense that you are going to have to fight for your rights to enjoy both the pains and the fruit(s) of your labor.

Hi Tim. Great piece. I, too, am interested in A Baby Story. In fact, in the last few years, I’ve given presentations on it at two conferences.

I agree that it’s refreshing to see the messiness in A Baby Story (ABS) in contrast to the “pain-free, worry-free, blood-free stories of birth that mainstream television has told for decades.” It actually shows the incredible amount of work during the apt-named labor! Also, your point about the narrative focusing on the childrearing is interesting. Each episode I’ve seen takes great pains to write the husband into the narrative. In fact, the men are often feminized within the text – and included within each step of the process. They showcase a softer, gentler generation of men/fathers than previously seen on TV. (Aside from the fact that every man I’ve seen asserts his masculinity within the show by talking about sports.) This, too, is a welcome change from the “stories of birth that mainstream television has told for decades.”

One final observation: I can’t help but notice that that no men have responded to this column. I’d love to hear their thoughts…