Television, Film and Creative Labor

The current Writers’ Guild of America strike has drawn much sniggering comment from the media and elsewhere. Such a response will be familiar to those who recall similar actions by writers in 1988 and by the Screen Actors’ Guild in 1999. ‘Don’t pity the poor pitiful striking screenwriters’, mocks Slate writer Jack Shafer, ‘let the major daily newspapers do it for you’.[1] Shafer reads coverage of the WGA strike as favourable and explains this as the result of shared interests on the part of a cosy cabal of fellow scribes. Shafer and others downplay the relentless pursuit of self-interest on the part of the Hollywood studios. Even the more balanced accounts have given credence to the ‘hard facts’[2] produced by corporate lobbyists. The high failure rates in TV and film are presented as evidence of the heartbreaking fragility of media businesses, in spite of perfectly their respectable profit margins and share prices. The offsetting of misses by hits and the widespread use of creative accounting are ignored. The system of paying residuals (small percentage fees for DVD sales and so on) to writers is portrayed as a curious historical legacy of a time when the movie and TV business made serious money. Not like now – ah, the poor, pitiful Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers.

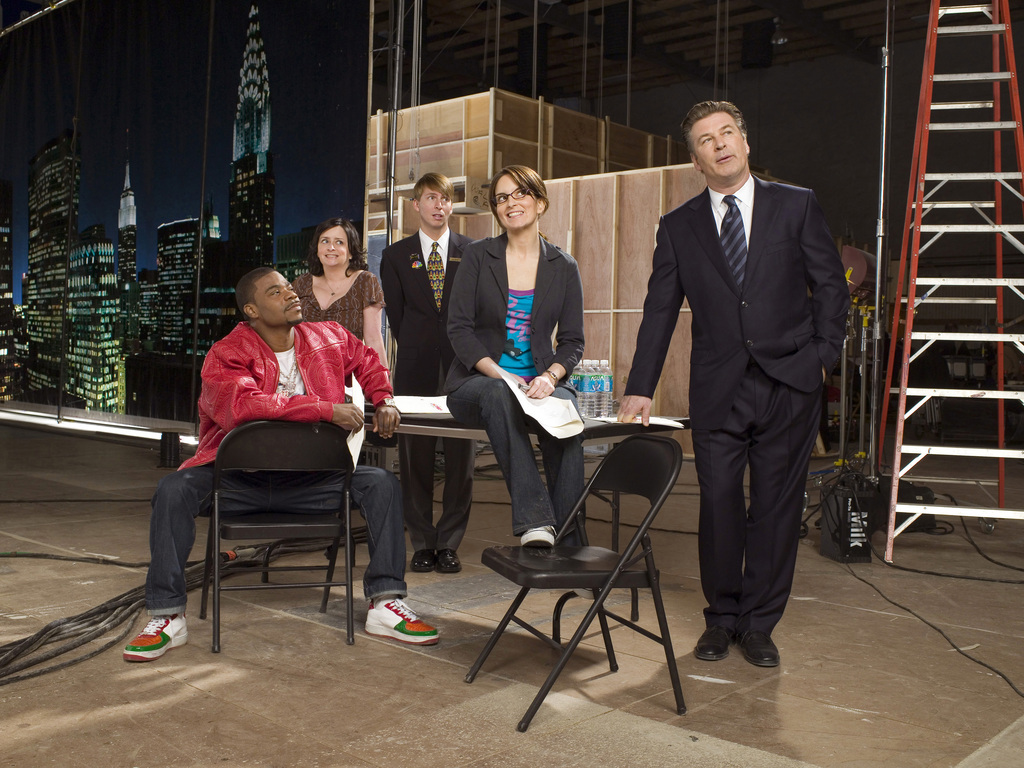

At work here may be the representations of creatives in recent TV fiction, most notably 30 Rock and Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. On the surface, these shows seem to elevate art over commerce. On occasion, they direct brilliant satire against the most venal aspects of corporate TV culture. Ultimately though, in order to maintain the dramatic and comedic tension, and to avoid charges of self-serving hypocrisy, these shows chicken out: the bad guy upstairs has to be sexy and actually quite smart beneath the management-speak; the creatives are funny but gormless, and can’t really be trusted.

It’s understandable perhaps that when the relatively privileged go on strike to defend their interests, even those on the left may be tempted to snort in derision. But such actions have the potential to draw attention to creative and artistic labour – not just in the film and television industries, but beyond them too.This is important because it’s almost universally agreed that such jobs are likely to become more and more important in modern societies – not just in the USA, where Big Media continues to thrive, but from Shanghai to Santiago, Manchester to Melbourne. This is partly why national and regional governments all over the world have been putting together ‘creative industries’ or ‘creative economy’ policies in recent years. They all want a piece of the information society action.[3] (The US federal government doesn’t have a policy to boost its creative industries, but that’s because it’s been boosting them since at least the 1920s; and in any case, US companies tower over the global media industries.)

As for what constitutes a creative job in a creative industry – that remains suspiciously murky in the various policy documents. It’s hard sometimes not to see the policy creativity cult as a way of making mundane jobs sound more satisfying than they really are. Nevertheless, what’s striking is that such policies rely on the real desirability of creative work. This is more than just media glitz, and the chance to brush with renown. It reaches back into historical understandings of art.

The sad reality of course is that most creative labour markets are riddled with inequality and insecurity. Survey after survey shows that the vast majority of artists suffer real poverty. Half of Australian artists in 2000-1 earned less than 7,300 Australian dollars from their creative practice before tax. Just as significantly, only half earned 30,000 Aussie dollars from all their activities[4] – all that waitressing, bar work, teaching as you wait for the big break still leaves you skint. Similar work all over the world echoes these conclusions.

Now it might be said in response that artists – writers, musicians, composers, dancers and so on (you know, the people who appear on television) – are from the educated middle class and so they get subsidised by their parents. The trust fund acts as the subsidy that keeps the artistic reservoir replenished. But if the means of artistic expression are confined to the educated and wealthy upper middle class, then that has worrying implications for the range of experiences that will be represented in modern societies. Ignoring cultural labour will only make this worse not better. Cultural policy is one way of correcting such problems (welfare policy is another) – but neo-liberalism is skewing such policy towards encouraging the unfettered growth of this kind of labour market.

By contrast, as everyone knows, the rewards for the most successful actors and writers are astronomical. As Robert H. Frank and Philip J. Cook explained in 1995, cultural markets are often winner-take-all markets, and this means that small differences in talent or effort often give rise to enormous differences in incomes.[5] The idea that talent will out and that this kind of extreme skewing of income reflects real merit is commonly heard in film, television and music (and among politicians and social scientists). As with the vast salaries and bonuses paid to sportsmen and business executives, this emphasis on individual merit downplays luck, social capital, and the input of the many other people who contribute to the success of individuals; coaches, teachers, team-mates, co-workers, mentors. Why then do so many people seek to enter artistic labour markets when they are so likely to fail? Are they stupid? No, reply the economists, just human: they do what most of us do and overestimate their chances of succeeding. This might have the economistic smack of essentialism, but there’s some truth there. Some suggest this is why most artistic workers are young: once people learn how likely they are to fail, they drop out and take up other work.

Another reason often given for the oversupply of artists (which of course depresses wages in the absence of exceptional success) is that such jobs offer self-expression and self-realisation: the labour of love argument. But as economies have changed, the meaning of this labour of love may be changing too. One way to understand this is as an appropriation by capitalists of the artistic critique of conformity and constraint.[6] Another approach is to ask, as Andrew Ross did in a seminal article on artistic (and academic) labour, what happens when pleasurable, selfless labour moves ‘from the social margins to the core sectors of capital accumulation?’[7]

One answer to this question may be that those involved in such labour are working harder and harder, internalising their commitments, and pursuing ever higher targets, in the belief that they are realising some true aspect of their selves – and yet feeling at the same time that something is curiously missing. The boundary between external compulsion and inner freedom gets pretty blurry. And in this respect creative workers may be typical of a pronounced tendency amongst those modern professionals to be ‘willing slaves’.[8]

Ross argued that those who share the experience of sacrificial labour need to organize themselves to resist these new forms of mental slavery. He also warned against underestimating the impact of such mental labour. The US creative guilds are not model forms of solidarity for the new capitalism to be sure. But if Ross is right, their actions shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand – any more than labour actions by those who work in universities. Television and film aren’t just battlegrounds over social meaning, they’re also fields of struggle over labour too.

[1] Jack Shafer, ‘Why Newspapers Love the Striking Screenwriters’, Slate, posted 13 November 2007, http://www.slate.com/id/2177835/nav/fix/

[2] Brook Barnes, In Hollywood, A Sacred Cow Lands on the Contract Table, New York Times, posted 5 August 2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/05/business/yourmoney/05steal.html

[3] See David Hesmondhalgh, The Cultural Industries, 2nd edition, London and Los Angeles: SAGE, 2007.

[4] David Throsby and Virginia Hollister, Don’t Give up your Day Job: An Economic Study of Professional Artists in Australia, Sydney: Australia Council, Sydney, 2003.

[5] Robert H. Frank and Philip J. Cook, The Winner-Take-All Society, New York: Penguin, 1996.

[6] Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, London: Verso, 2005.

[7] Andrew Ross, ‘The Mental Labour Problem’, Social Text 63, Vol. 18, number 2, 2000.

[8] Madeline Bunting, Willing Slaves: How the Overwork Culture is Ruling Our Lives. London: Harper Perennial, 2005

Image Credits:

1.The 2007 Writers’ Strike

2.The Cast of NBC’s 30 Rock

3.SAG Members Protesting Elizabeth Hurley Crossing the Picket Line

4.home page thumbnail image

Please feel free to comment.

Great column, David. As far as the self-representation of middle- and upper middle-class “creative” labor goes, I wonder whether something like The Devil Wears Prada could be included as well, since magazines depend on the unpaid labor of twenty-something “interns” who move to New York in the hopes of scoring a real job at a Conde Nast publication. Which of course rarely happens. In any case, this was thought provoking…I’m definitely going to look up the Andrew Ross piece that you cite here.

Nicely put, Dave. I was just at Futures of Entertainment 2 in MIT, and one of the industry antagonists of the moment on the first day also tried to make the “poor industry” pitch that they don’t have the 4c of residuals to give, since they’re making no money whatsoever. Which seemed hilariously nonsensical, like a restaurant manager saying “I didn’t make much money this week, so I can’t pay the chef.” It’s so disheartening that when television and film continue to bring in huge revenues, the industry still tries to play the “pity the poor industry” card.

As John mentions, I’d imagine the notion of “glamor professions” comes in a bit here as well; writing seems like it would be a fun and exciting way to make a living, ditto art, or architecture, or music, and perhaps even academic work. Because of that aura, these professions are able to attract people more than willing to gamble that they’ll make it big. The economic pressures though mean that many, even those who may be the most passionate and talented, will have to go to their backup careers long before that’s even a possibility. I think the point about the impact of representations of certain professions weighs in is a good one. It’s easy to forget how much of writing is actually work. This doubtless affects public response to strikes by creative workers at least as much as it affects the career ambitions of upwardly mobile young people.

Pingback: FlowTV | Spoilers at the Digital Utopia Party: The WGA and Students Now