Mobility, Mobilities and Communication Studies

I would like to thank FlowTV for inviting me to serve as a guest columnist. It is with pleasure that I take this opportunity to raise some issues in Communication Studies from north of the border. Specifically, I would like to focus on the place of “mobility” and “mobilities” in the discipline. Why are we modifying technologies with mobile? What kind of license and imagination is granted with the modification of technologies with mobile? What does the shift to mobile signify? What do we gain or lose by modifying technologies with mobile instead of digital? My sense from the literature is that we are in the midst of a conceptual shift from time, space, and place to ‘mobility’ to better explain and understand the post-modern west and its shifting economic, social, political, religious, and cultural practices. Is our discipline the site that should be taking up this concept? What value does this concept hold for us to intervene, resist, interrogate, refuse and/or liberate theories and practices in Communication Studies? How does mobility get deployed in other disciplines, most specifically geography, from where it has migrated? What kinds of residuals remain from mobility’s movement from one discipline to another? How do we address relations between moving, movement and mobility? I will use the first column as an opportunity to forward some of the terrain, terms, definitions of mobility and mobilities. In the second column, I will examine how these ideas manifest themselves in a mobile practice that is having difficulties transitioning (moving) from one platform and set of practices to another, mobile television. At the end of the series, I hope to come to a better understanding and consideration of the ways in which we may want to consider mobility and mobilities in Communication Studies.

For the last three years, I have worked on two large-scale interdisciplinary research projects focusing on wireless communications. The first research project, the Mobile Digital Commons Network (MDCN), brought together five different institutions (Banff New Media Institute, Concordia University, York University, Hexagram, and the Ontario College of Art and Design) with a range of skill sets including designers, engineers, social scientists and artists to develop and implement mobile experiences in the Canadian context. The second research project, the Canadian Wireless Infrastructure Research Project (CWIRP), has been exploring various models for the delivery and implementation of Wi-Fi networks.

I relay my involvement with these projects as part of my reflection on thinking through ‘mobility’. In both of these projects, I was confronted with, almost on a daily basis, the lack of disconnect between the promises of mobile technologies and their implementation, the policy context shaping the cost, regulation, and take up of cellular phones,1 the ways in which the metaphors and our experiences of ‘old’ media are used to understand and negotiate the ‘new’, and the different creative and problem solving strategies of the various constituents in our research project. Each of these items alone could be a column onto itself, but I want to relay the context from where my reflections on ‘mobility’ come from — from a material interaction with mobile technologies — the making, creating, testing and assessing of two mobile experiences — Urban Archaeology: Sampling the Park and The Haunting — and extensive case studies of Wi-Fi networks.2

A simple, and popular strategy, to consider mobility is to turn to the OED. In this context, mobility is represented as:3

1. a. The ability to move or to be moved; capacity for movement or change of place; movableness, portability.

b. Movement or capacity for movement of a limb, part, or organ of the body. Also: liability of a limb, part, or organ to be abnormally displaced.

c. Ease or freedom of movement; capacity for rapid or comfortable locomotion or travel.

2. a. The ability or tendency to change easily or quickly; changeableness, instability; fickleness. Now chiefly literary.

b. Tendency or susceptibility to rapid emotional change; impressionability; excitability. Now rare.

c. Tendency to change expression readily and frequently; fluidity of facial expression; expressiveness.

3. Mil. The ability of a military force or its equipment to move or be moved rapidly from one position to another.

4. a. Chiefly Physics. The degree of movement of the particles of a liquid or gas; the mobile quality of a liquid or gas.

b. Chem. and Physics. The degree to which a charge carrier undergoes movement in a definite direction in response to an electric field.

5. Chiefly Sociol. The ability or potential of individuals within a society to move between different social levels (more fully vertical mobility) or between different occupations, etc. (more fully horizontal mobility); the ability or potential of a workforce to move from place to place.

6. Geol. and Ecol. The degree to which a substance (e.g. a mineral, pollutant, etc.) tends to be transported in a medium or system, or dispersed from its point of origin or introduction.

In his most recent book On the Move, Tim Cresswell (2006) examines the origin stories of the use and understanding of mobility in the western world. One of his many important insights is that movement and mobility often have positive connotations. He suggests that these associations are critical to interrogate to grant mobility more explanatory power.

He ends On the Move with the following:

“In this world it is important to understand that mobility is more than just about getting from A to B. It is about the contested world of meaning and power. It is about mobilities rubbing up against each other and causing friction. It is about a new hierarchy based on the ways we move and the meanings these movements have been given” (265).

Is it meaning and power we should be taking up more explicitly instead of moving and mobility? How is our discipline implicated in meaning and power by our take up and modification of communications and communication technologies with mobile? What do we lose and what do we gain? In the next column, I would like to further explore these ideas and think through their place in Communication Studies.

Image Credits:

1. Urban Archeology: User in the park with GPS and iPAQ. (Photos: M. Longford)

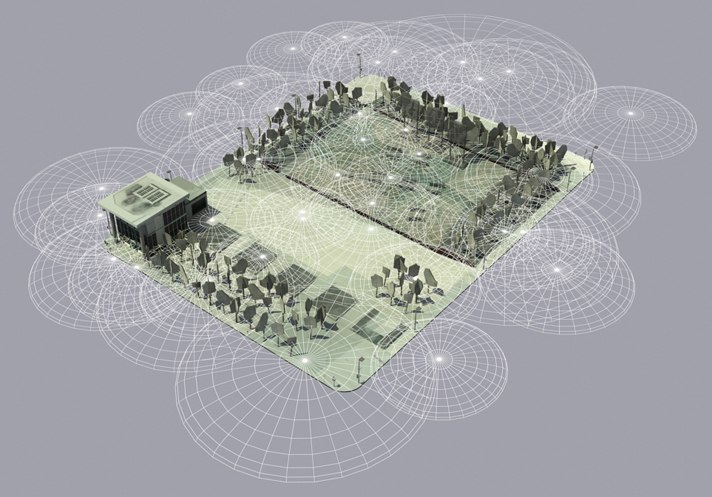

2. Urban Archeology: 3D Maps of hotspots tagged with GPS coordinates. (Illustration: A. Morris)

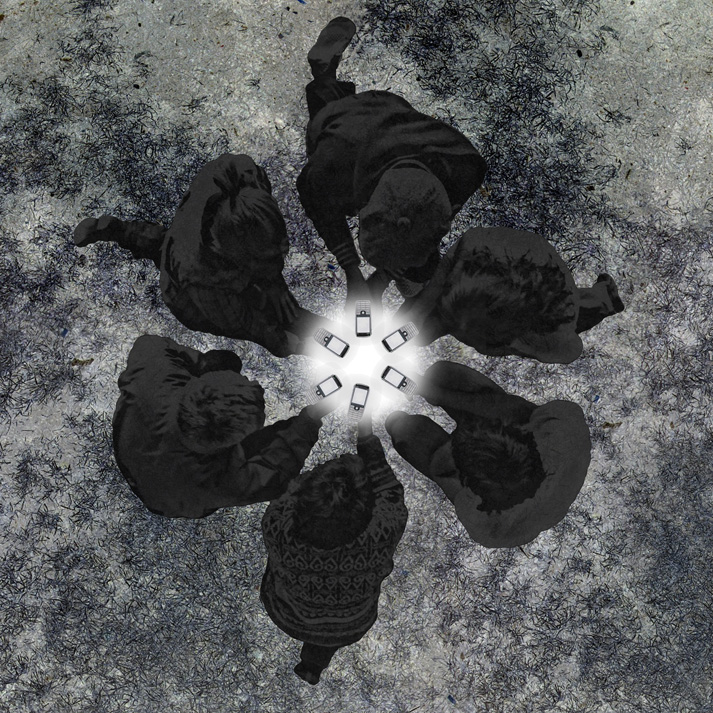

3. The Haunting – Using the metaphor of the Ouija Board as an interface for Mount Royal Park, Montreal. (Illustration: A. Landry)

4. The Haunting – Players in Mount Royal Park. (Illustration: L. Palmer)

Please feel free to comment.

- “At the end of 2006, Canadian wireless phone subscribers numbered 18.5 million, representing a national wireless penetration rate of approximately 58%. Recent CWTA research estimates wireless penetration in major urban centres has exceeded 70%, with some greater metropolitan areas approaching the 80% mark.” http://cwta.ca/CWTASite/english/index.html, accessed May 13, 2007 [↩]

- My colleagues and I have tried to address some of these issues in Wi: The Journal of the Mobile Digital Network and its more recent manifestation as wi: the journal of mobile media (forthcoming February 2008, “Pedestrian Traffic”). [↩]

- OED [↩]

You bring up many interesting points and I am interested to read the next column. I wonder if our need to be mobile is more a matter of the technology as already created and therefore available for use as opposed to an actual need for it. Without a consumer culture would we still feel the need to be always connected with one another?

Very informative!

Nowadays – a time of new technologies and unlimited possibilities, this approach to life closes before you the path to incredible achievements, no matter what area of life you touch. That is why a modern person should have the same quality as mobility. Lots of students must learn and understand it to be successful. WritingCheap is an excellent resource for young people, which helps them to develop important skills.