Youth, representation, and the contemporary history of Canadian TV

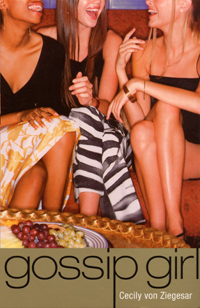

Many scholars, fans (especially adult fans), and producers whose work/object of admiration might fall under that vast parachute called “youth” or “teen” TV will attest that, despite the cultish quality of so many such products, their regard within both broader segments of the cultural industries and audience cohorts is often marginal, verging on the disdainful. Much teen TV inhabits a potentially lucrative yet paradoxical space that is often seen as unavoidably mainstream and yet attracts a vast number of avid viewers of the type associated with decidedly non-mainstream media texts. Youth products tend to win few awards even when they are highly innovative and intensely adored. They are largely ignored in the press as well, unless they feature taboo storylines or debauched, barely-dressed celebs. The most visible examples of American teen TV are often considered guilty pleasures of some kind or other—because they are “bad” network products (Gossip Girl, The O.C., The Hills) or the hybrid offspring of “bad” cult genres (science fiction, gothic horror, animation).

Anglo-Canadian TV does offer a few examples of both of these particular forms of teen TV spectacle, into whose looming and almost all-purpose maw we could put everything from Buffy to the aforementioned O.C. We do, and have long, however, produced a good deal of youth and teen TV—more than our share perhaps—of a different variety, owing at least in part to a slightly different heritage/parentage[1]. Here I refer to the debt the public-TV, documentarian tradition Canadian English-language television owes the National Film Board of Canada and to the public funding structures to which all our national TV producers are beholden. Thus a great deal of teen TV produced in Canada “looks” and “sounds” more like My So-Called Life or Saved by the Bell than Buffy or The O.C.[2] The fact of this (over)production, as well as the types of products being produced (and for whom) tells us something about one of the roles Canada plays in the global TV market; further, in examining the televisual youth culture produced in Canada, we can learn about the spaces in which technological innovation and the production of national cultures and voices intersect, and how this renders these cultures and voices visible or relegates them to the still relatively invisible margins in very particular ways.

I see a pattern emerging between the marginalization of teen TV as a multi-generic text type (for lack of a better term, calling it a genre seems awfully reductive) and the marginalization of Canadian TV more generally. In talking to producers there is a sense that teen TV is often overlooked by the industries, but it is precisely this marginalization that has allowed Canadian producers to carve out this niche for themselves while the more traditional strong-armed players (in this case Hollywood/the U.S.) produce more conventionally recognized adult fare[3]. Canada thus plays its particular part in the TV market, producing a variety of products for youth.

The Canadian youth market, of course, isn’t monolithic. There are shows that are co-pros or that can, do, and have traveled out of Canada with relative invisibility. You might say they are able to pass as American and in so doing circulate with impunity through American markets and through global markets in which Americanness is privileged. I am thinking here, for example, of a lot of shows that are produced for YTV and its subsidiary channels (15/Love, Danger Bay). Other shows work through more traditional—that is largely public and national—funding structures. They adhere more visibly to the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) mandates about the representation of social difference and the uniqueness of Canadian identity. Some have gained great popularity (and sometimes also notoriety) in other markets; one group through the production of community-centred historical narratives of white–Anglo youth (Road to Avonlea, Emily of New Moon), another through the narration of youth-centred stories of urban multicultural life (Degrassi, Northwood, Edgemont). While these narratives have tended to be marked—literally or figuratively—as Canadian products detailing Canadian stories, they have garnered wide acclaim for their importance in producing social difference while maintaining the capacity to circulate widely. At least one other category also exists. These are still more marginal, sometimes locally-produced, televisual products. They sometimes have production values that are equal to those of the other shows discussed, but they have little chance of circulating beyond limited regional or national spaces (Renegadepress.com, Moccasin Flats, Drop the Beat).

Technological innovation, especially the development and widespread use of digital technologies, has leveled the international playing field in TV production somewhat. For a long time a major criticism of Canadian TV was that it was immediately identifiable by its “cheap” look as not being American. The professionalization of actors, especially with the prolific growth of the youth culture market, also changed the “look” of Canadian television. Today, viewers are less likely to notice the Canadian mark on internationally-circulated televisual products because of their production values or unfashionable, chubby, acne-riddled actors. But what, if anything, does this do to the potential for a distinct voice to emerge from Canada’s TV industries that deals with the youth market?

The idea of a national voice is of course problematic itself, suggesting the potential for some sort of unified culture. There idea of a national voice has, in Canada, largely meant a voice which is not American or Americanized, that is, produced to be legible as American rather than Canadian (again, to “pass”). It is interesting that Canada has established itself as a global purveyor of so many goods on the youth TV market. But the way that these products circulate, and their ability to circulate in particular ways that articulate something that might be recognizable as distinctly Canadian voices, is marked by their ability to pass (relatively) unfettered by this distinctiveness[4].

Notes:

[1] As Geoff Pevere and Greig Dymond noted in 1996, “By 1996, Canada was holding the position of the second-largest creator and exporter of children’s television in the world” (116). What they consider children’s television is a bit up for debate, as they include in their list of “hits” shows from Mr. Dressup to Degrassi. However, this resonates with the fact that youth TV has not historically had its own department in production houses, and has often fallen within the production parameters of children’s or family TV.

[2]As Serra Tinic has eloquently addressed, Canada is a tremendous zone for the production of cult American TV, especially science fictions series like The X-Files and Battlestar Gallactica. Canada had produced some noted teen science fiction as well, such as the series MythBusters and Deepwater Black. However, most of these were co-productions with few links to Canada as a unique narrative site.

[3]This is resonate of how netlets have operated as somewhat marginal spaces within the broader US TV grid.

[4]At least within the TV market. How these products circulate within broader online matrices is a more complicated issue.

Images:

1. 15/Love

2. Gossip Girl

Please feel free to comment.