‘Screenifying’ Choreography: The New Parameters of Social Interaction as Envisioned by Bill T Jones’ Blind Date

Dancing Duck in Bill T. Jones’ Blind Date.

Overtures

Get all your ducks in a row. Everything is just ducky. We are sitting ducks.

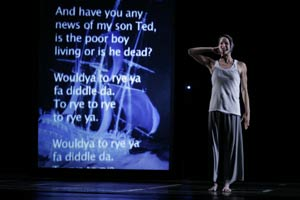

Thoughts bubble as I contemplate the 5 screens of various sizes, a large hanging frame, and a narrow, long canvas/scrim painted with what appear to be a row of rubber duckies. Blind Date has not officially started, yet it has. The curtain is open and text scrolls, flashes and dissolves across the screens; but the ducks do not change. Smiling, they waddle irresponsibly. Danger, duck crossing. But they never do. Static, they are magnified and embodied as the piece continues. A dude forced to make a living selling Ducky burgers and three large carnival-ride looking plywood ducks began to proliferate the duck motif. Dancers enter and exit the stage in precision marches that meander and loose count of bodies. The ducks hang just in the balance, sitting. “ME!” yells a falling body on stage. Other dancers scramble to catch that person before she hits; before he hits; before they hit. Feathers are flying figuratively, but the ducks are still, jolly.

Screens fly out, scrims fly in and one panel stays; faces dissolve high middle stage. They look like anyone. The audience is left wondering whether or not these are not faces of people but victims. Grotesques now, the ducks have waddled off. A soldier is talking to the business man figure (played by Bill T. himself) about never-ending, borderless, indistinguishable war. I am jolted: we are all sitting ducks pretending that everything is just ducky, thinking that we have our ducks in a row so we’ll be fine when our turn comes to yell “ME!” We recite screenified platitudes, aping knowing gestures about war mongering as if that is all the social interaction required to make it stop. “Couch potato” is a thing of the past. There is agency in accepting one’s reality from a screen when one is a dumb ass sitting duck and it is an inability to figure out the choreography required of screenified interaction.

The screen has become a prerequisite facilitator of daily movement for the allegedly productive 21st century lifestyle. Screens are mobile, and increasingly tied to microprocessors. While there is a growing body of work analyzing screens and their ubiquitous presence in our lives, the work of Heidi Cooley is not to be missed, I’m interested in their musculature: their work, placement, messaging, and activity. I will attempt to think about the CPU, the message (image/data), and the messenger (corporation, person) as the appendage to the screen. Moving alongside Blind Date and a series of mundane tasks, I draw attention to the terpsichore set by the parameters of the tech’s body in conflation and contact with our own: the screenifying of movement.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YN_OMFETtY0[/youtube]

An amalgamation: bodies + images = screenified choreography

Why is it not Mediation?

Simply put, screenified interaction is a non-experience of subtle adjustments to the spinal column and weight distribution driven by the presence of screens. Human contact becomes exertion positioned in close proximity to a CPU and screen. The screen is meant to simplify the event. However, it situates avoidance and neglect as the baseline for social choreography by augmenting the transactional over the inter-relational. Absorbed into the calculations of a cash register while pacified by a video panel at the check-out line or mesmerized by a self-illuminating TV

The screened machine: Pump as it plays.

at the gas pump, the person inside the physiological expanse of the body quickly fights or accepts its new role: sitting duck. The helpful intrusion of the CPU’s lack–flesh and self-control–feints individual acknowledgment. “And by the grace of God, one day I will give this up!” howls Bill T Jones’ business man character, holding up his cigarette, cursing and pleading with God to rid him of his sumptuous curse.

It could be argued that the human-cum-consumer also has little if any self-control in “the point of decision making” when confronted with the mosh of “content” emblazoned across nifty panels owned and “fed” by companies like SignStory, and Gas Station TV. Blind Date shows that in the living room, the point of decision making about major political issues, people encounter difficulty with foreclosed choices offered as “selections.” The particular mixture of advertising and alleged news reporting makes it quite difficult to see the gun barrel pointing out of the duck blind. Crafting elegant and satisfying ways to have interaction during a transaction involving screens has become a time-consuming venture.

Enter a big box or major grocery store and a battalion of screens are deployed across the space. They look official and exude authority reminiscent of transportation terminals, but destinations are purposefully obscured. Seeking direction, you stand in front of a messaging screen waiting for an answer to a question you’ve long since forgotten. Unsettled, you find calm by meandering. Rediscovering “shopping event,” more things land in the cart, echoing their representations on screen. Time to pay: person or kiosk? Checkers are surrounded by screens, is there really a difference? The panel above the conveyor belt is rigged with a feed offering “news,” lest you notice the passage of time in your body. Your screens allow you to pay without cash and extend the panopticon around the checker who is conducting real-time inventory through a recessed screen. Her key pad often sits to her right, underscoring the assumption that the scanners are infallible. I can hear you laughing.

Multitasked and screenified, the checker’s focus and body are split across space, through time, and with rhythm. What was once a simple algorithmic march that closed face to face with heart muscles aligned, is now a dilemma that engenders passivity or malevolence. Quack. The video panels offer no real options: zone-out to the media feed; become agitated by the frequency range of small speakers; or rage against the distraction/intrusion from/into one’s own life. Isn’t it just ducky?

Well then . . .

Screens are encapsulations and projections. They are limits, boundaries beyond which we dare not imagine a passing image. Drawn in so close to something that feels exactly right, we instead adjust our neck in a futile attempt to avert our gaze, but the screen has swallowed us whole, not sutured us, or hemmed us in, but we could continue to think about stitches in order to make sense of the machine’s body copulating with our own. A quadrangle, the screen creates neat order, our muscles, and therefore our emotions, adjust accordingly. Our desires have absolutely no bearing on the cartography of the screen. Though we might struggle against its certitude at different junctures because we should know better, ultimately, it is that force of four corners which indicates that there is no need to run and scant little space for hiding–submersion is perhaps the only act permissible from the screen.

Blind Date investigates what it means to assume one’s ducks are lined up, ready for action. Even if/when the action appears preempted by the projections, momentum redirects to the messaging flesh. No newcomer to screened dance, Bill T. Jones very early in his career harnessed the choreographic power of projected and televisual images. Indeed, a great deal of his work investigates the corpo-reality engendered by long stretches of TV watching. That he now positions this body as a very active force in our social landscape should come as no surprise. In fact, it is quite masterful as he leads the audience in the theatric space deeper into the cosmos of the “dummy box.”

Several rooms, empty spaces, echo chambers are effected by the screens. The lines on the floor which demarcate their absences as they fly in and out become screens, too.

They highlight the fact that a screen is an entrapment, an encasement, a casket, a parameter, a box, just a couple of meaningless lines unless something is projected across it. Sitting ducks, the bodies whir and toss themselves in clockwork precision gone askance, tuning back in with popular dances and formations one would see on YouTube. The dancers in counterbalanced extremities, reach just beyond the frame for contact more meaningful than the gesture itself. Mining habitual movement, movement meant to heal like yoga asana, cohesive movement like marches and line dances, Bill T. Jones reveals a culture deliberating itself, but under the mistaken idea that it can be done on a screen, without acknowledging the programmers ensconced in the feed, the code, lingering in the cpu’s fleshless body.

Image Credits:

1. Dancing Duck, photograph by Paul B. Goode

2. Blind Date: montage by Janet Wong

4. Ensemble number, photograph by Paul B. Goode

5. Screen text, photograph by Paul B. Goode

Please feel free to comment.