Institutions That Fail, Narratives That Succeed:

Television’s Community Realism Versus Cinema’s Neo-Liberal Hope

Television isn’t exactly known for portraying the lives of the urban poor or the rural lower-classes in honest and realistic ways. And it certainly hasn’t offered such portrayals as compassionately as it did in last season’s episodes of The Wire and Friday Night Lights—or so it seemed to me as a former resident of Baltimore and a person who grew up in the rural Deep South. Both series offered narratives of tremendous warmth and empathy toward characters that viewers could care about and embrace, yet simultaneously wrapped such feelings within heartbreaking stories that dealt with the tragic components of these characters’ lives and worlds.

At one level, tragedy is an overriding theme of both narratives. In The Wire, we see lives lived in the midst of an almost total breakdown of social institutions and civil society. The writers and producers—former journalist David Simon and former police officer turned junior high teacher Ed Burns—tell a tale of contemporary Baltimore where inner-city residents struggle to survive within, around, and under an obliterated urban landscape. The institutions of politics, police, schools, and the economy are beyond dysfunctional, tending instead toward the toxic. Yet amidst the chaos, lawlessness, violence, and despair, citizens somehow still struggle by. Last season’s focus on four junior high school kids portrayed the critical juncture of adolescence in inner-city America—would these kids be sucked into the underground economy (and its almost certain ticket to the morgue) or could the institutions of civil society (i.e., the public education system) provide them another alternative? What we learn is that the results are predictable, but not guaranteed; more the play of luck (both bad and good) than fate. What we also learn is that these narrative fictions are also stand-ins for real lives in real communities with real-life consequences, which truly makes it all very, very sad.

In Friday Night Lights, the tragedies of small town Texas are writ small in the lives of its characters. The star quarterback of the high school football team becomes a paraplegic because of the game, and then watches in horror as his parents sue the coach and school because they need the money to provide for his care. The cheerleader’s storybook future as his wife unravels with the injury, while her family is crushed by the weight of her father’s persistent philandering. A running back and his brother raise themselves because they can’t stand their alcoholic father. The running back’s ex-girlfriend watches her single mom make one bad choice after another with men. And the replacement quarterback must care for his grandmother with Alzheimer’s because his father is fighting the war in Iraq—and seemingly prefers war to being at home. The broken institution here is not school, but family. And as with The Wire, the portrayals are all too real.

Yet all of these tragedies are not something that can be solved by the coach, the central character of the drama. In fact, his personal success (as a man with ambitions beyond coaching high school ball) is dependent on his players’ ability to overcome these tragedies through their own initiative, skill, and perseverance (as opposed to the typical trajectory of such a narrative which usually inverts these roles). But the coach is no fool. He realizes what is at play in the field, telling his team to remember that “what we have is special, that it can be taken from us, and when it is, we will be tested.” This is not some rah-rah half-time speech, but a recognition of the harsh realities of existence that have only just begun to test the kids in the larger game of life. Football is not an elixir in this narrative, and if anything, football creates additional pressures and stress for the individuals involved. Yet it also serves as a powerful unifying and rallying force for people who typically have little to cheer for in rural small town life.

What also made these two television narratives stand out as exceptional for me was their stark contrast to two similar narratives appearing simultaneously in movie theatres—Freedom Writers, starring Hillary Swank, and We Are Marshall, with Matthew McConaughey. Both stories mirror the setting of these television narratives, as well as their focus on tragedy. Freedom Writers is the tale of a public high school English teacher in inner-city Los Angeles working with students whose lives have been decimated by gang warfare and broken homes, yet who nevertheless participate in an educational system that is little more than a holding station before they meet their inevitable fate. We Are Marshall is a football drama set in a rural West Virginia college town trying to overcome the loss of its team and community members in a fiery plane crash. Both films are based on “real-life” people and events, and hence, are sold to audiences as true stories.

What distinguishes these two films from The Wire and Friday Night Lights is how simplistic and thoroughly reductive their narratives are. Both feature communities that have suffered from violence, traumatized to the point of hopelessness and despair. Yet both films employ the mythological hero tale to provide the redemptive narrative. The saviors appear from outside the community, arising from seemingly nowhere (perhaps the organic matter that is the dirt of American “goodness”). As outsiders, they are immune to the pain and suffering that cripples those around them. It is through their irrepressible spirits and naiveté that they are able to overcome doubt, cynicism, fear, and institutional obstruction and intransigence. Both heroes embody the neo-liberal hope of American society—the lone individual who through sheer force of personality and perserverance rises, against all odds, to success and victory while helping the less fortunate along the way.

In Freedom Writers, the teacher has no conception or understanding of the war taking place between her black, Latino, and Asian youth when school is not in session. Once these kids teach her the realities of urban life, the message she returns to them is that all they need to do to overcome the pain and suffering in their lives is to believe in themselves and their inner feelings, and when they do, all the violence, drugs, illiteracy, racism, ethnocentrism, mistrust, brutal cops, lazy teachers, deadbeat dads, predatory boyfriends, vengeful peers, teenage pregnancy, and historical record will disappear. Indeed, as the narrative proceeds and the kids begin following her therapeutic advice of “telling their own stories” in journals, these dysfunctional yet all too real communal realities simply drop out of sight. In the end, the audience learns, society, institutions, family, and community don’t really matter—only the will of the individual. Write a different narrative, the teacher seemingly says, and all your troubles will disappear. Furthermore, embrace the story of other victims (Anne Frank and Jewish Holocaust survivors) for your inspiration. See how they survived state-sanctioned violence (never mind the six million plus who didn’t) to see that you too can survive the same. But first and foremost, believe in the white liberal do-gooder wearing pearls and smart business suits.

The narrative of We Are Marshall isn’t much more nuanced. Rather than cancel the football program after the tragic accident, the university decides to field a new team the following year. The problem is that no one in the community—either the town itself or alumni of the university—is willing to take the job as head coach. Yet a new coach magically appears from outside the community, and in turn, overcomes all obstacles to lead his team of upstarts to victory in their home opener. Grief and tragedy are overcome through competition. There has been a disruption, but the return to normalcy occurs thanks to the courage of, and belief in, the heroic individual—the coach. At one crucial moment, the head coach lectures another coach on the importance of simply playing the game as the only true means of communal redemption. “What matters is that we play the game,” he argues. “One day we are going to be like every other team, where winning is everything, and nothing else matters. And when that day comes, that’s when we’ll honor them.”

We Are Marshall and Freedom Writers represent the classic American narrative that Hollywood has mastered and replicated with great frequency and alacrity: through competition and self-reliance, individuals can overcome the constraints of community and failures of social institutions. But also, it is that lone individual who refuses to succumb to (even thumbs his or her nose at) these constraints that we should follow. Through the leadership of such individuals, we will find redemption for the tragedies that consume our lives. The message here is neo-liberal, but I suggest it is also one with fascist overtones (the celebration of the will of the charismatic leader; the belief in his/her vision and triumph, despite the costs1). Furthermore, it is exactly this type of repeated Hollywood fiction—one that feeds our “hunger for consolation, meaning, and hope”2—that lays the ideological groundwork for public belief in such go-it-alone figures as George W. Bush in similarly tragic and traumatic historical times.

Although derived from real-life communities, The Wire and Friday Night Lights are fictions that ultimately reveal much more honest truths. The heroes to rally around do not exist, have departed, or will not alter the world by the twinkle in their eye. The institutions that fail them nonetheless continue to play important roles in structuring their lives. The tragedies experienced cannot be washed away by fleeting victories or introspection (which only provides temporary solace). Communities are awash in tragedies, both large and small, but only through community can such tragedies be understood, if not entirely overcome. And despite the breakdown of civil society in inner-city America, such communities are still inhabited by human beings—including innocent yet fearful children—who deserve more than our seeming lack of empathy, attention, or resources.

In that regard, television has offered us stories that are more real, humane, and pluralistic than the mythology Hollywood regularly provides. Television’s narratives cast an unblinking eye on characters and facets of American life that are rarely treated with honesty or respect. They offer much needed pluralism to the stories that permeate public life. David Gutterman summarizes Hannah Arendt’s argument about the importance and availability of such narratives within society: “The ‘meaning of public life’…is found when a common object or story can be seen and heard—and assessed and judged—such that ‘human plurality’ rather than ‘singularity’ or the ‘unnatural conformism of mass society’ defines the shared world.”3 [And if anyone has studied the fascist potentials of a culture overly fixated on the singular individual and mass conformity behind his indomitable will, it would be Arendt!]. Television’s realistic portrayals of communities trump the tired neo-liberal formulas of Hollywood. Institutions will continue to fail us, but only one set of these narratives succeeds in offering “human plurality” in all its messy and complex reality.

Notes:

Image Credits:

1. (a) The Wire

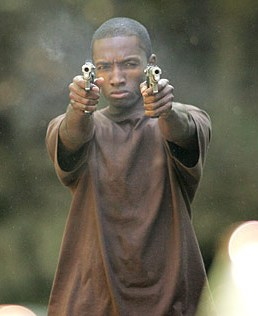

2. (b) Marlo Stanfield of The Wire

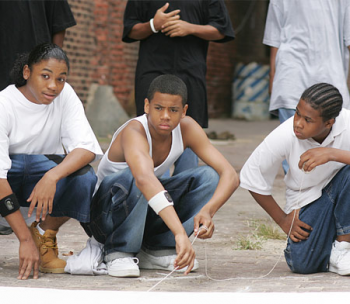

3. (a) Duquan ‘Dukie’ Weems of The Wire

4. (b) Randy Wagstaff of The Wire

5. The Cast of Friday Night Lights

6. Coach Taylor of Friday Night Lights

7. (a) Jack Lengyel of We Are Marshall

8. (b) Freedom Writers

9. Hilary Swank in Freedom Writers

10. We Are Marshall

11. The Wire

Please feel free to comment.

This is a great piece. Although it’s a generalization, I have noted the tendency, especially in the mainstream, for film to lean into the neo-liberal wind, leaving television with the space for somewhat more critical renderings. I have just been talking with one of my undergraduate classes about the article “Fictional Truths and Truthful Fictions: The Death Penalty in Recent American Film” (Dow, Constitutional Commentary, 2000) and he makes a somewhat similar point about the capacity of fiction to find its way into spaces that stories that begin with the myth of “truth” often fail to find.

As a devoted “Friday Night Lights” fan, I first want to praise you (and other critics in the national media) for calling attention to the show’s persistent quality. Many reviews (see Nancy Franklin’s recent piece in The New Yorker) comment on the fact that FNL’s premise is one from which academics/high brow viewers might shy. Its thematic center, after all, is high school football. Or is it? As you note above, I think it’s far more the dysfunction of family. It’s also the “real” experience of a working class town that’s essentially been hollowed out by changing economic conditions, much as my own home town has been by the rapidly down-sizing pulp mill.

As Franklin emphasizes, “It’s hard to say what’s great about Friday Night Lights without feeling that you’re emphasizing the wrong thing, because although the show’s particulars are distinctive and special, it seems not to be made up of parts at all — to be just an organic whole. In short, it feels like life. The show isn’t merely set in the world of West Texas football; it IS that world.” What it offers, then, and what you so skillfully emphasize, is something quite foreign to the cliched sports or savior-teacher film. Instead of predictable narrative arcs, FNL ricochets all over the place. Like We Are Marshall, it weaves together the lives of the small town it presents; completely unlike We Are Marshall, its characters are densely constructed, and even at times unknowable (I’m thinking specifically of both Coach and Riggins, whose motivations and nuances have only increased through Season One). The cast of We Are Marshall appears to be an embodiment of a grief textbook, with each character legibly performing a different hue in the rainbow of grief. Yet life reads nothing like a textbook.

Having seen the first episode of Season Two, I’m scared that a certain melodramatic plot twist might lead FNL into less mainstream, Hollywood-plot territory. The twist rang incredibly false to me, a response I can only attribute to the fact that all that came before rang incredibly true.

Now that’s a great line, Annie (“The cast of We Are Marshall appears to be an embodiment of a grief textbook, with each character legibly performing a different hue in the rainbow of grief”). I couldn’t agree more!

Jeff, I’d completely agree re: The Wire, especially given its strategy of adding another institution each season, so we don’t just see an institution failing, but a complex mess of institutions dragging each other down. Season 4 is particularly heartbreaking, given our familiarity with films (and many other tv shows) that take such kids as those who star in S4, and “rescue” them. Meanwhile, McNulty is the anti-Hillary Swank, who tries to help; see how that works out for Body or Randy, though, and you get a more realistic sense of how individuals are placed in these institutional messes.

This piece raises the important issues of set direction, costuming, and art direction in general in film and television. Part of what I find so effective about Friday Night Lights is its realistic interiors and domestic spaces, its costumes that look like that those teenagers might actually wear, rather than a parade of the latest expensive mall fashions.

As long as television is considered to be a commercial medium ripe for product placement the quality of programming will suffer. If a producer must choose to dress a program’s sets in consumer objects to help finance production, what hope do we have for plausible set direction? The economic imperatives of producing network programming are at odds with the realistic depiction of working-class and lower-class spaces.

After all, who wants to rush out to the mall after watching an hour of socio-economic inequality and injustice?

Excellent piece. Take a look at Tim Gibson’s article in this issue. It might spark some interesting cross-commentary.

I agree Jonathan. HBO used to have an interview with David Simon on its website where he discussed how each season they have focused on a particular civic institution. It is as if they literally want to document the breakdown of society, one brick at a time. But as you say, it is the interplay of these factors and forces that makes for great social documentary–even in the realm of fiction.

This is a really insightful piece. I’ve come to the point where I am strongly turned off by film such as Freedom Writers or We are Marshall for all the qualities that you describe. That type of film almost takes a stance that belittles the struggles of the students by presenting them with the simplistic solution of faith and the belief in ones self. It becomes frustrating to watch, when I relate to the struggles of the students until the “saviour” cleans the inner city streets, schools, homes and all is right, quant and wrapped up in 120 minutes of a “true story”. I fear too many people in the audience walk away assured that this “savior” is common in inner city schools and can feel good when they walk away that the problem is being solved. Their conscience can rest assured that they don’t have to look further into the issue because some nice girl like Hillary Swank is taking care of it. I have never watched Friday Night Lights out of fear that it would encompass the qualities of Freedom Writers, but I am happy to hear it strays far from it. I thank you for clarifying that!

Pingback: Television & American Culture Syllabus | anne helen petersen

Your personal post, “Institutions That Fail, Narratives That Succeed: Television’s Community

Realism Versus Cinema’s Neo-Liberal Hope | Flow” was truly

worth commenting on! Really wanted to say you did a

wonderful work. Thanks for your time ,Laverne

The first thing I thought of after seeing The Wire/Freedom Writer juxtaposition in your piece made me think of hearing that The Help — a film about a firebrand journalist ‘helping’ reveal prejudice in the south — had won an oscar after watching Season 4 of The Wire. In it, a disgraced police officer becomes a teacher and ultimately forms a connection to a promising child who will ultimately become a drug addict [names redacted in honor of fewer spoilers]. Both bits of media are, ultimately, an attempt to play upon emotion. Even further, both tend to be focused on white characters, but the power those characters ultimately possess regarding the lives of the people they’re trying to help differ.

The Help is a satisfying story, and it’s true-ish. The lady stick is to the racists, buddies up with the folk, and then racism ultimately ends at some point. The Wire is deeply (and purposefully) unsatisfying. David Simon almost revels in setting up would-be hero moments for the characters and then, true to the first season’s chess metaphor, reveals their place within the machine limited by various symptoms of the human condition. The Wire is a show that ultimately limits the agency of its characters in a previously-unseen way. Cops don’t catch their guy, childhoods aren’t magically fixed by white people on a mission, yet somehow the story seems to hit a writerly poeticism that few others have managed. It’s good and makes you think, as did your article.