Watch Now: Netflix, Streaming Movies and Networked Film Publics

by: Chuck Tryon / Fayettesville State University

In this article, I am interested in thinking about some of the ways in which the computer appears to be supplanting both the movie screen and the television set as the crucial site for encountering and consuming Hollywood films, while also acknowledging the role of place in shaping media access, not only in terms of the kinds of texts but also in consumption practices. While scholars such as Barbara Klinger and Anne Friedberg have increasingly focused on the home as a site for watching movies, I have begun thinking about the computer in terms of the formation of networked film publics, with film audiences increasingly organizing and finding each other on the web. In this context, I will be looking at the new Netflix “Watch Now” player, which allows viewers to watch high-quality streams of selected Netflix movie and television content.

In her June 29, 2007, Flow column, “Dish Towns USA (or Rural Screens) Part One,” Joan Hawkins describes the ways in which media access is often limited in certain sections of rural America. Building on Gregory Waller’s observation that most histories of movie spectatorship describe urban experiences, Hawkins convincingly argues for a need to look at what she calls “Dish Towns,” the rural communities, often spread out over dozens of miles, marked by hundreds of satellite dishes. She goes on to describe the poor quality of cable television and the lack of choice at nearby movie theaters, but for my purposes, Hawkins’ observations point to need to think about the role of geography in shaping access to certain media texts.

Hawkins’ comments about these Dish Towns reminded me of my own experiences with media and place. In the fall of 2006, I moved to Fayetteville, North Carolina, a medium-sized military city best known for its connection to Fort Bragg. When I first moved to Fayetteville, after several years of living in either Washington D.C. or Atlanta, one of my first major questions was whether or not there was an art house theater. Fortunately, Fayetteville has the Cameo Art House Theatre, a locally-owned theater in the city’s slowly recovering downtown neighborhood. The theater’s two screens offer more than enough to satisfy my art house movie needs, and the local ownership is responsive to community interests and tastes.

Finding a good video store, however, turned out to be more difficult. Like many smaller cities, the only stand-alone video stores are the major chains, Blockbuster and Hollywood. Access to art house and independent movies on DVD requires a Netflix membership, and so despite my preference for skimming the shelves of local video stores for a forgotten classic or a new discovery, I have reluctantly joined the Netflix generation. While Netflix offers a selection that exceed most video stores, in the first year or so that I had a Netflix membership, I found that I watch fewer movies and that I have even felt “obligated” to watch a DVD that has been sitting next to my TV for several weeks, its bright red envelope collecting dust. I mention these details in part because I believe they illustrate the ways in which place can shape one’s experience of film culture, but also because these viewing practices may soon change as digital distribution of movies increasingly appears to be a feasible alternative or supplement to theatrical distribution. While it is something of a cliché to describe movie watching practices as being in a state of perpetual transition, the various forms of digital distribution raise important questions about the relationship between movie watching and configurations of public and private space.

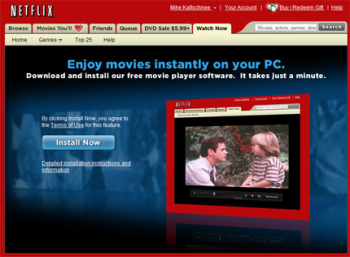

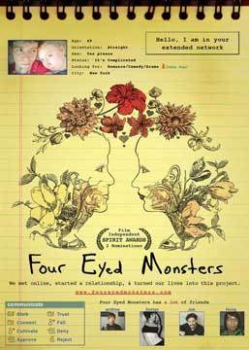

It is within this context that I have begun experimenting with Netflix’s “Watch Now” player, which offers customers at a certain membership level the option to watch some of its movie and television content online. While much of the conversation about digital distribution has focused on independent filmmakers, such as the maker of Four Eyed Monsters, who have distributed their movies via YouTube, I am much more interested in thinking about the of online distribution of Hollywood films. While watching the movie online may not substitute for seeing a movie projected on a big screen with a large audience, the high quality streams are adequate, producing a fairly impressive level of detail. And the rudimentary player offered some of the basic time-shifting controls of pausing, rewinding and once the film is fully loaded, skimming ahead. That being said, the “Watch Now” player currently works only in Internet Explorer, which can be annoying for those of us who use Firefox or other web browsers. And the streams appear to lack the “extras” that I have normally come to associate with home viewing on my DVD payer—the director’s commentary tracks, deleted scenes, and other information that I have come to regard as a significant part of my domestic film experience. That being said, it’s easy to imagine a near future in which some or all of these DVD extras could be streamed as well.

In a sense, the Netflix Watch Now option parallels the already existing practice of making episodes of certain TV series available online; however, the focus of Netflix on movie rentals seems to represent an important shift in how we access movies and our relationship to wider public film cultures. The Watch Now option feeds the desire for immediacy or spontaneity associated with trips to the video store. Audiences are not forced to wait the 2-3 days for that little red envelope to show up in the mail. While using the Watch Now player, I’m more likely to browse the available films by genre or groupings—in my case independent films and documentaries—to find DVDs that conform to my current mood or immediate needs, something I’m finding more difficult to juggle with my often stagnant queue. Instead, as I’ve watched online, I’ve found myself watching movies more frequently than at any time in the recent past, while being more willing to take chances on certain movies, based in part on the perception that I’m making a relatively spontaneous decision, one that won’t result in a movie sitting on my shelf for several weeks at a time.

My Watch Now choices are somewhat informed by the networked film publics structured around the film blogging communities and film-oriented social networking sites in which I participate. Thus far, I’ve been able to watch three films on the Netflix player, including The Candidate, which I watched because of a friend’s enthusiastic blog entry, and Loud QUIET Loud, a documentary about the Pixies, which I watched simply because I like the Pixies and never got a chance to see the film in theaters. I also watched Darfur Diaries, a short documentary about the crisis in Darfur that I was considering for my fall course on “Documenting Injustice.” In all three cases, the decision to watch felt relatively spontaneous, as I skimmed the selections looking for a movie to “rent,” but the choices were also structured by the films available through the streaming service and by the Netflix algorithm for identifying films that would conform to my tastes based on my ratings of films and on the ratings of others who have similar tastes (an algorithm that is surprisingly accurate).

And yet I find myself facing some reservations about the ways in which this “Watch Now” option structures how I watch movies at home. The streaming option currently feels like a highly individualized viewing experience targeted for individual consumption. Netflix is rumored to be working on a set-top player that would allow consumers to transfer movies from their computer to their TV screen, but arranging for more than couple of people to gather around a laptop screen to watch a movie might prove difficult. And the service, like Netflix in general, is framed around a model of consumer choice that needs to be interrogated. In addition to the movies I mentioned, I also watched a preview episode of the new Showtime series, Californication, featuring former X-Files star, David Duchovny as a New York novelist finding himself navigating what he takes to be the shallow Hollywood film industry, while also managing to seduce virtually every young woman who crosses his path, prompting jokes that the series should be called “The Sex Files.” While the episode was mildly entertaining—I probably won’t continue watching—I found myself increasingly aware of the ways in which Netflix was shaping my available viewing options by promoting the preview episode of a new TV series, in the hope of generating buzz for the show and new subscribers for Showtime, suggesting the ways in which media convergence, to use Henry Jenkins’ phrase, opens up new possibilities for selling media content. In conclusion, the Watch Now player introduces some important questions about how digital distribution will reshape film and television reception, as well as to what extent the Netflix model anticipates or shapes a networked film public.

Sources consulted:

Friedberg, Anne. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2006.

Hawkins, Joan. “Dish Towns USA (or Rural Screens) Part One.” Flow 6.3 (June 2007).

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Klinger, Barbara. Beyond the Multiplex: Cinema, New Technologies, and the Home. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Image Credits:

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: The Chutry Experiment » Watch Now

Pingback: Movie Downloads: The Pros and Cons - Movie reviews - Spout

Pingback: FlowTV | S, M, L, XL: The Question of Scale in Screen Media

Pingback: qzdepot » Blog Archive » Watch Now: Netflix, Streaming Movies and Networked Film Publics

Is there any other kind of articles related to this one? I would want to

research a little more about this article!!!! :-) I truly love your main articles,

but I really need more information and facts regarding Watch Now: Netflix.

Thanks for your insight!!!

Great! Thank you for this list. Try this site http://putlocker.as/. Also not bad, probably worth adding to your list.

Hello

I use to stream movies via NetFlix, the video quality is really good but it’s pretty expensive for me. Thus, I just went through your write up, it’s really useful.

Thank you

Annie Lobo