Notes from Economy Class

by: Eric Freedman / Florida Atlantic University

On a recent flight to London, rather than sleeping, I spent most of the trip watching television, my eyes fixed to the back of the seat in front of me. This was my first excursion on Virgin Atlantic and my introduction to V:Port, one of three different types of inflight entertainment systems found across their fleet. The V:Port system is featured on the airline’s 747-400s and A340-600s and offers video on demand; much like an at-home on demand system, passengers can watch or listen to what they want, from a selection of films, television shows, games, audio programs and interactive elements (most notably IMap, an application that allows passengers to track their flight and explore different destinations and points of interest around the world) stored on the system server, and can start, pause or rewind their selected downloads. The onboard systems host 300 hours of on demand content, accessed through a searchable database that also allows users to bookmark their favorite programs, in effect creating a multimedia play list.

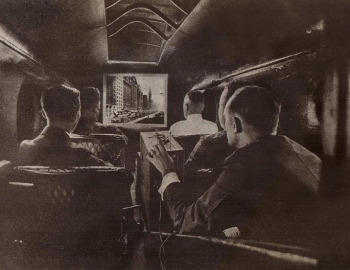

As a digital system, V:Port provides a notably different experience than traditional single-channel systems that subject every passenger to the same content on the same schedule; older analog delivery systems are also prone to a host of mechanical issues. V:Port is only one evolutionary touchstone in the history of inflight entertainment. The World Airline Entertainment Association lists 1921 as the year of the first inflight movie when Aeromarine Airways screened Howdy Chicago!, a tourism film, to its passengers during the city’s “Pageant of Progress”. A screen was hung in the front cabin of the 11-passenger hydroplane and a suitcase projector was secured to a table in the aisle. As sightseers flew above the city, highlights of the area appeared on screen. In 1961, David Flexer formed Inflight Motion Pictures and engineered an aircraft projection system that adapted the Kodak projection mechanism to fit into a shallow ceiling area of an aircraft interior; TWA is often touted as the first real exhibitor of inflight movies, deploying Flexer’s system. Competing airlines Pan Am and American opted to pursue video systems, and installed black and white TV monitors on their airplanes; passengers viewed movies on these closed circuit systems, which consisted of approximately twenty cabin monitors. In the early seventies, Trans Com developed an 8mm film cassette system; whereas airline mechanics were employed to operate earlier inflight entertainment systems, the compact cassette interface allowed flight attendants to change movies in flight and add short subject programming. By the end of the same decade, video projection systems were developed by several competing companies, including Avicom (which emerged from Bell & Howell in Chicago) and Matsushita. Video revolutionized the inflight entertaiment industry, boosting the number of operable systems across the airline industry fleet and diversifying content to include a broader range of information and entertainment programming.

But the point in this chronology that is most relevant to this essay is the introduction of the in-seat video system in 1988; Airvision produced the system, which used 2.7 inch LCD displays, and Northwest began trials on its B747 aircraft. These systems are now an industry standard, though cabin mounted monitors are still common on older aircraft. As a cost saving measure, most airlines upgrade their seats once every five to ten years, and many planes have not yet been retrofitted with small screen seat technology. Two basic small screen systems exist—the distributed system that uses personal screens and a tuning mechanism that allows passengers to choose from scheduled programming broadcast from a central playback system, and the on demand system that features a personal playback unit that permits passengers to cue up programming at their discretion.

Phil Lewis, the managing director of seat manufacturer Contour suggests that few airline seats offer an improvement to mid-century standards: “The fundamentals are the fundamentals. You go back to a seat we produced for BOAC in 1948 called the Slumberette. Okay, it had the space, it had the bed, the only thing it didn’t have was the complex electronics.” [1] Yet seat design is an ideologically inflected enterprise, a project tackled by design subcontractors. Virgin Airlines partnered with London-based design firm PearsonLloyd in 2003 to revamp its economy and premium economy seating line, spending over $25 million on a project that began by reexamining the historical constraints on airplane seating, a collaborative endeavor that not only yielded new manufacturing strategies (while holding onto traditional concerns for overall equipment weight and safety), but also considered more ephemeral notions of personal space. Describing its economy seat, put into service in 2006, the firm’s on-line catalogue details, “Alongside significant improvements in both comfort and space, the major innovation is the introduction of a back pack on the back of each seat, which draws together all the functional elements used by the aft passenger and gives them ownership of this part of the seat.” [2] When the head rest moves up, the back pack stays put; this strategy, the designers suggest, creates an illusion of more personal space, visually dividing the back of the seat ahead from its front.

Founded in 1979, the World Airline Entertainment Association represents airlines, airline suppliers and related companies committed to the development of inflight entertainment (IFE) and communications. Affirming the importance of IFE, the WAEA points to passenger satisfaction and branding, suggesting that IFE is a means to differentiate one airline’s service from another’s and goes on to relate, “To some extent, IFE is an effective way for an airline to express its own national or regional character.” [3] IFE is also big business in the technology sector, with a number of distinct patents on file for aircraft seat assemblies that include integrated electronic systems for signal decoding, signal routing, data management, and power conversion (systems that commonly include a video display unit, an audio system, and/or a telephone).

The airline seat is an often-overlooked signpost of convergence—a site of convergent media, convergent functionalities, convergent spaces, and convergent subjects. The seat is designed with the needs of two passengers in mind (the one seated and the one looking, an interlocking arrangement permutated throughout the cabin) and zoned accordingly; if designed correctly, neither party should be aware of the other’s presence, the two dependent on the same object yet engaged in a certain studied indifference effectuated by technologies that promise to envelop the senses as well as by the seat’s very architecture. A piece of furniture with state of the art technology, the airline seat accommodates sleeping, working, eating, and leisure (though some of these functions are more easily managed than others), and more significantly condenses these otherwise separately spatialized spheres of activity—it collapses what are commonly distinct zones of engagement on land, where they are subject to more willful (yet escapable) moments of condensation. Perhaps what I am detailing warrants a return to Guy Debord’s consideration of what he termed “psychogeography”, of the impact of the geographical environment on individual behavior. Engaged with the study of commodity fetishism, extending the work of Karl Marx and George Lukacs, Debord suggested that alienation was not just an emotive state, but a consequence of mercantile forms of social organization, with capitalism as a zenith. But my interest at the moment is not in the invasive or seductive potential of the spectacle—the degree to which an embedded screen technology lulled me to sleep. Rather, my focus is on the translation of an eight or so hour flight into a decided number of television episodes, feature films, and soundtracks—a very deliberate numerical equation, with time, geographic displacement and pleasure quantified as an objectified form of discourse, translated into a certain number of visual and aural signifiers.

Among the educational sessions of the WAEA 26th Annual Conference (held in 2005 in Hamburg, Germany) were panels on the “Specifications for Digital Content Management”, “The Impact of ‘Anywhere’ Entertainment”, and “The New Seat/IFE Architecture”. As the catalogue descriptions suggest, these sessions confirm that digital media is the future of IFE, and to this end they scrutinize both marketplace (examining synergies across markets) and audience (analyzing potential generational shifts in the airline passenger profile, and the consequent shift in content, interface, and infrastructure demand).

As a media scholar attentive to television and its industries, I am now presented with a series of other industries with which I need to engage. What started as a simple perceptual exercise, examining a content stream (consuming both film and television, watching Hot Fuzz, Notes on a Scandal, Extras, and Doctor Who, and immediately noting I was drawn to all things British on my flight to London—perhaps engaging with objects I had wanted to consume, but simply not had the opportunity) and considering my spectatorial engagement in the public space of an airline cabin (subjected to other people’s choices—overhead cabin lights on or off, window shades up or down) while screening work on another passenger’s back (seat back up or reclined), became a study of my fascination with Virgin Atlantic, clearly the result of their engagement with video on demand. This is not a promotional piece for the airline, but a reflection on the value of a particular investiture. The airline’s engagement with new technology was what satisfied me, and outweighed any other index of their customer service. It seems the airline seat, as the armature of IFE, is the ideal commodity fetish; it envelops the body, is designed for comfort, and at the same time, it yields a set of spectacular images. Its value is two-fold—holding up a series of signs, and yet a sign itself; a sign of a certain labor power, of both an industry engaged with an apparatus and of passengers who have enough capital to reap the rewards of this engagement, one that extends the all-too-familiar embrace of the screen.

Notes:

[1] Richard Quest and Shantelle Stein, “Airlines go flat out for comfort,” CNN.com, December 30, 2005 (http://www.cnn.com/2005/TRAVEL/12/13/airline.chair/index.html)

[2]http://www.pearsonlloyd.co.uk/upload/html/econ_01.html

[3]http://www.waea.org/faq.htm#8

Image Credits:

2. Aeromarine inflight screening

4. V:Port Cabin: courtesy of the author

Please feel free to comment.

hi nice post, i enjoyed it

I think this is an interesting article it was really useful! here is more in this blog about How to change imap to pop3 in outlook 2016?, it is more familiar to me! keep doing awesome. instructions on Data Recovery Software Services and Support kindly follow our site.