Indigeneity for Life: Bro’town and Its Stereotypes

by: Ilana Gershon / Indiana University

IN ADDITION TO OUR REGULAR COLUMNISTS AND GUEST COLUMNS, FLOW IS ALSO COMMITTED TO PUBLISHING TIMELY FEATURE COLUMNS, SUCH AS THE ONE BELOW. THE EDITORS OF FLOW REGULARLY ACCEPT SUBMISSIONS FOR THIS SECTION. PLEASE VISIT OUR “CALLS” PAGE FOR CONTACT INFORMATION.

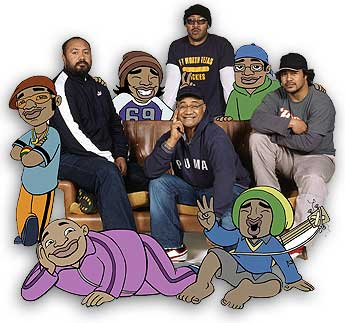

Bro’town creators and characters

The South Park sensibility has traveled all the way to New Zealand. Bro’town, an animated television series clearly influenced by South Park and The Simpsons, focuses on five schoolboys, four Samoan Pacific Islanders and one indigenous Maori, and their adventures in an urban working class neighborhood called Morningside. When this show first aired in September 2004, controversy quickly bubbled around it. Academics such as Melani Anae and Leonie Pihama argued that Bro’towns’ portrayals were racist and enforced widespread and unwelcome stereotypes about Pacific Islanders and Maori. Journalists began to raise this question in every interview with the show’s writers, asking whether Bro’town was racist. The writers uniformly responded by pointing out that they make fun of everyone on the show. This isn’t a terribly satisfying answer to the accusation of racism — equal opportunity stereotyping only seems to sidestep the issue. Here I want to discuss how Bro’town disavows many of the principles structuring ethnic identity in New Zealand. Through this rejection, the show provides a critique of how what it means to be ethnic ends up limiting people’s interactions.

In New Zealand, issues of indigeneity haunt every relationship the nation has with a minority group. Since the late 1970s, the indigenous Maori have been increasingly successful at persuading the New Zealand government to heed its obligations to respect and promote Maori well-being. This is widely acknowledged to involve seeing New Zealand as a bicultural nation first and foremost, and a multicultural nation only within the context of Maori’s prior demands for social justice. Practically, this means Maori are the dominant group shaping the New Zealand government’s policies towards minorities. This takes two forms. First, the gains Maori have made in gaining funding and infrastructure support are eventually also provided to other minorities. When Maori receive government support for language pre-schools or funeral leaves from work, other minority groups will have the same opportunities a few years after Maori do. Second, and what I focus on here, what it means to be a minority is largely shaped by how Maori politicians and activists have explained to a general New Zealand public what it means to be Maori. The ethnic in New Zealand is a Maori-inflected ethnic.

Maori have had to pay a price for their relative success, they have had to engage with the New Zealand nation’s politics of recognition. It is not just the state that is being called upon to recognize certain groups’ rights or histories. The groups themselves have to perform in a way that is recognizable. People constantly and repetitively demonstrate the already agreed upon markers of their ethnicity — that in acting as themselves they are also engaging with the range of stereotypical qualities linked to the identity that people attribute to them. Now that does not mean that people have to perform their stereotypes in their entirety or without parody. But to be properly recognizable, people have to engage with these stereotypes, and have to engage with these stereotypes in such a way that does not challenge the most fundamental assumption of a nation’s politics of recognition — that people possess ethnicity, race, or culture in an inalienable way. In short, ethnics are asked to perform an essentialist relationship to identity.

Bro’town characters

In New Zealand, the self-mimicry that ethnic groups have learned to perform in response to the government’s “Hey you” emerges out of a historical dialogue Maori have had with the government in their efforts to change government policies. For indigenes more than any other ethnic group, radical cultural difference of a particular type frames the ways in which they can articulate their claims on the state. Indigenes are presumed to have knowledge of what traditional laws and other social practices used to be prior to colonialism or other encounters with a transformative modernity. They do not live according to these principles currently, because they are forced to navigate the treacherous demands of modern life, such as the capitalist market. Not all nations demand that ethnic identity has operates in this way. But in New Zealand, every ethnic group’s identity is framed in relationship to Maori — the indigenous functions as the ur-ethnic in this particular ethnoscape. As a consequence, when the NZ states asks — “how are you an ethnic group?” — every ethnic must respond with an explicit account of what their culture is in terms already agreed upon between Maori and the NZ government.

What is striking about Bro’town is the television series’ systematic refusal to do this. When I first started watching Bro’town, I was caught by the ways this show never addressed many of the concerns about culture that I kept hearing about while doing fieldwork with Samoan migrants. The show never refers to fa`alavelave, the Samoan ritual exchanges that everyone who goes to a Samoan church or a Samoan wedding or funeral comes in contact with. The show never discusses concerns widespread in Samoan communities that Samoan children are not learning how to be properly Samoan. Or portrays Pacific Islanders with large extended families — the only person with a complicated family is Jeff the Maori, who has eight dads and one mother — a parody of the nuclear family instead. In short, the show skirts questions about what it means to be culturally Samoan, focusing instead on the consequences of being a relatively generic brown minority with Pacific Island markers in this particular ethnoscape.

But the show does more than simply avoid answering with culture to the question of ethnic identity. The show also depicts every character as a pastiche of phrases, with characters often recycling other people’s words or sayings. This primarily takes place through code-switching — characters are constantly peppering their language with words or phrases that mark their ethnicity. Characters don’t only codeswitch ethnicity markers — they reference songs or other people’s catch-phrases. These juxtapositions happen not only at the level of words, but also in terms of who populates the series. Every Bro’town episode opens in Heaven, with Jesus portrayed as a slightly annoying teenager and God as a tolerant and wise, and very well-built Samoan father — marked especially as Samoan by the tattoos. Jesus has frustrating interactions with various historical figures, and God always has to intervene with words of wisdom. When John Lennon shows up in heaven, the point of the scene appears to be to insert as many John Lennon song lyrics as possible into an intelligible conversation. With scenes like these, Bro’town writers avoid making ethnic markers the only source of codeswitching. Ethnicity becomes merely one of many markers that the characters animate and juxtapose.

The white characters on Bro’town are an intriguing exception. They too will make pop culture references, but the other codeswitching they do is invariably about the ways they engage with racism. The white teacher of Maori language is constantly using Maori words, and then defining them immediately afterwards in an attempt to visibly accept Maori and other Pacific Islanders. Intriguingly, she is the only person on the show who codeswitches ethnic markers that are not her own. Other white characters are also defined largely in terms of how they treat people of other ethnicities. For example, the white South African teenage bully is invariably portrayed both as a sycophant and as a racist, someone who is bringing a racism fostered elsewhere to New Zealand. In this case, his racist comments are phrases that circulate from another ethnoscape.

Bro’town cast

While Bro’town does not do away with stereotypes altogether, the show does provide an alternative to the ways New Zealanders construct ethnic identity. It offers a vision of ethnicity that does not rely on essentialized cultural markers. Instead, ethnicity is one marker among many that people recycle through their words and practices. In addition, the show offers a strong critique of any attempts to make ethnic relations hierarchical — no ethnicity should be privileged over any other ethnicity. Throughout the show, government representatives in particular are frequently criticized for trying to position some ethnicities as more valued than others. For example, whenever the police are called, they inevitably suggest that the boys or parents call back when any other ethnicity other than a Pacific Islander is in trouble. Capitalists too are attacked for implicitly trying to insist on ethnic hierarchies. The villians of very first episode of Bro’town were a secret wealthy white cabal who wanted to rig a quiz show for high school students. They did not want brown students to be successful, and sought to maintain an unequal ethnoscape. In short, Bro’town uses pastiche as a rebuttal to any effort to value ethnicities in relation to each other. The show insists instead that ethnicity can be but one of many ways to express differences that distinguish but in the end do not determine people’s futures or friendships.

Bro’town explores the question: is it possible to engage with stereotypes without being racist? In exploring this question, the writers insist on a distinction between stereotypes used to reinforce historically and economically grounded inequalities and stereotypes used to indicate differences without consequences. Through various plots, the writers insist that difference alone is not enough to spark violence or economic disparities. The show offers the possibility that ethnoscapes in themselves do not necessarily disadvantage people. Too fittingly, this is an animated show that uses cartoon drawings as a vehicle for arguing for the possibilities and advantages of flat ethnic relations in real life.

For futher reading:

Bro’Town’s website

Fairburn Dunlop, Peggy, and Gabrielle Sisifo Makisi, eds. Making Our Place: Growing Up PI in New Zealand. Palmerston North, NZ: Dunmoore, 2003.

Sissons, Jeffrey. First Peoples: Indigenous Cultures and Their Futures. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2005.

Image Credits:

1. Bro’town creators and characters

2. Bro’town characters

3. Bro’town cast

Please feel free to comment.

Wow! bro’Town on Flow! I know it has made some export sales but, not yet to the USA. Still, this my encourage some American colleagues to seek it out.

Do you agree that that it seems to have less cultural significance, as it moves into the third series? Certainly, the first series was the topic-of-the-moment .

kia ora

bro’Town has been on basic Canadian television (APTN) for a while now.

Great to see Bro’ Town discussed on the normally highly US-Centric ‘Flow’ (Congratulations on the Mexican & Latin American issue too – more please!) This is the 2nd year I’ve been teaching Bro’ Town in my TV course in Sydney, Australia, and it’s hard to find any material on it. so this piece is very welcome. It would be nice to think the program might someday get an airing on US TV as well as in Canada. I don’t really agree with Ilana’s contextualisation of the program in terms of Aotearoa identity politics – although I haven’t lived there for quite a while, I don’t think the place is quite as anally retentive as it used to be, or that ‘ethnics (whoever they are) are asked to perform an essentialist relationship to identity’ or that ‘For indigenes (whoever they are – terribly essentialist term by the way) radical cultural difference of a particular type frames the ways in which they can articulate their claims on the state’. I think things are much more fluid than that, and maybe Spivak’s ‘strategic essentialism’ has some leverage here, but I think you’ll find many Aotearoans, at least in the Auckland that I know quite well, engage in highly transnational and transcultural forms of identity politics. At the same type wok by writers such as sarina pearson suggest that notions of ‘indigeneity’ have become much more fluid in NZ, and applied to diasporic Pacific islanders as well as Maori. One of the important things about Bro’ Town is that it carcicatures the prime miister Helen Clark along with many other NZ celebrities, Maori, pakeha, Pacific Islander and ‘other’, and dares to be politically incorrect in a similar way to ‘South Park’, which to me is the only US TV program that adequately reflects the current state of the US. Maybe the Ehiopian character ‘Starvin Marvin’ who used to be in ‘South Park’ shares a lineage with ‘Bro’ Town’ in terms of satirical portrayal of ethnic minorities. The episode of ‘Bro Town’ I use in class is ‘The Wong One’,because it plays off ethnic stereotypes of Hong kong Chinese in Aotearoa with Maori and PI stereotypes. It’s curious that ‘Bro Town’ worked far better than ‘Sione’s Weedding’ the film its creators, the Naked Samoans, a stand-up comedy group of some long standing in NZ, released a couple of years ago, which has crudities and banalities in its ethnic stereotyping which don’t work half as well in dramatic comedy as they do in animation. In any case, the important thing is that ‘Bro Town’ has been embraced by NZers of all ethnic persuasions, and by Maori, Pacific island and pakeha NZers in Australia as well as something that expresses their identities and debates around biculturalism and multiculturalism (terms which probably mean much differnet things down under than their equivalents in the US). The first 2 series of Bro’ Town’ have been shown on Australia’s multicultural chanel SBS, which also screens ‘South Park’, and have, I believe, contributed to an erosion of rigidly politically correct debates about ethnicity and indigeneity in Australasia (ie Australia and NZ).

i think u guys did a good job……… morning side for life….peyow peyow

Pingback: Faye Ginsburg, “Embedded Aesthetics: Creating a Discursive Space for Indigenous Media” « MC250

its a good cartoon except for the racist jers now and then.

so what about the racist jers??? im a pacific islander and im not ashamed thats where all pacific families started and why try hide the truth when it is reality in MOST not all island families…. i think bro town was and is a success despite their early departure the program is still a hit!! Now all them plastic islanders who hate dont try whiten up because societys views but embrace this show bcoz we all know u ddnt find the milk and honey straight from when you came on ur banana boat here!…. i think Bro town should ressurect and show on all nzers tv screens again!!!

ps if white people created this program then theirs something wrong their but our own “boys from the hood” produced and made this program so dont hate congratulate!

Pingback: Week 8 – Munro Hall

Pingback: Works Cited list – Charlotte Wallis

amazing love it!