Beyond DRM

by: John McMurria / DePaul University

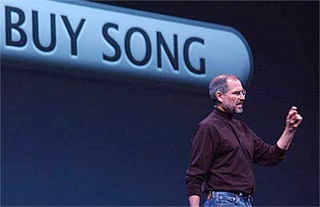

Steve Jobs

When Steve Jobs posted his “Thoughts on Music” on February 6, 2007, calling for the eradication of digital rights management so that downloaded mp3 music files could be played on any listening devise, growing consumer dissatisfaction with DRM regimes had come to a head. The event was significant given the market dominance of Apple’s iPod and their success in getting the big five music labels to make their songs available for download on iTunes for 99 cents per song. But the manifesto was less than magnanimous as Apple faced opposition across Europe for tying its download service to its proprietary mobile mp3 player using its proprietary FairPlay DRM software. During the summer of 2006 consumer rights agencies in Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Germany claimed that Apple’s DRM violated copyright law. In August 2006 France passed a law giving regulators the authority to require Apple to license FairPlay to other makers of MP3 players, which Apple called “state-sponsored piracy.” The Dutch consumer protection agency joined the opposition in January 2007 and advised consumers to stop buying iPods and quit downloading music from iTunes, and instead buy generic mp3 players and download music from DRM-free services such as eMusic, which does not carry the big five’s labels but offers a range of independent music. Recently Norway ruled that Apple’s DRM strategy was illegal and the Norwegian consumer protection agency called for Apple to make FairPlay available to competitors by October 1. Microsoft and Sony were not intimidated by this and created their own proprietary DRM-protected music services tied to their own music players. In his statement, Jobs said DRM licensing would be untenable because its secrets for protection would be leaked, though critics have pointed out that Microsoft has been successful in licensing its DRM system. The internet content innovator ZDNET, a network of CNET, produced a much watched video that lambasted all of these DRM strategies as CRAP, or Content Restriction, Annulment and Protection.

In addition to pressure from consumer advocates, Apple had incentive to scrap DRM because after nearly four years of selling songs on iTunes, only 3% of the music on users’ iPods was downloaded from iTunes. An independent study found that iTunes sells only 20 songs per iPod sold. Apple is therefore less dependent on iTunes to attract iPod buyers than the music conglomerates are in finding successful models for profiting from music downloads to offset losses in DVD sales. Research at Yahoo suggests that consumers would pay 20 percent more for music downloads if there were no DRM restrictions, indicating that DRM curtails demand for pay per downloads. In a different strategy, last year Microsoft agreed to share a portion of the sales price of its new Zune mp3 player with Universal Music. Warner is looking to cell phones as a potentially more secure network for copy protected music downloads. Ad-supported music downloading sites including Spiralfrog and Qtrax are developing new revenue models and have attracted the major labels. But the promises of these services were put in doubt at the recent Midemnet industry trade show in Cannes when these two services failed to announce launch dates and a panel of young music fans unanimously agreed that audio ads sucked.

Zune Squeeze

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a legal advocate for “internet freedom,” has proposed “Voluntary Collective Licensing” for music distribution. This entails the music industry forming a collecting society that would allow music file-sharing for those who volunteer to pay $5 per month. These funds are then distributed proportionally to music artists based on the volume of downloads. Since 1914 similar licensing arrangements have been formed by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI), and the Society of European Stage Authors and Composers (SESAC) for radio and television broadcasts. Unlike “compulsory licensing” which legally enforces the universal collection of fees, such as those that cable and satellite carriers pay to carry over-the-air broadcast programs, the government-weary EFF counts on “market forces” and voluntary good citizenship on the part of file-sharers and corporate music labels. A more far reaching proposal came from the French parliament in December 2005 when it introduced a bill for compulsory licensing for music and video over the internet that included an 8 to12 Euro added fee to broadband service. While receiving strong support from the left, the Green Party, the center right UDF and consumer groups, the French government bowed to intense opposition from the powerful music labels and killed the bill. The Universal Music Group vigorously opposed the legislation, as one commentator explained, “When you’ve reached 30 per cent market share, when you’ve pulled off the last big merger, when you’ve built up the barriers, there’s not a lot of benefit from equalizing access.” Meanwhile, the International Intellectual Property Alliance, an association that represents Hollywood and the US software and publishing industries, has lobbied the US government to eliminate compulsory licensing in countries around the world.

Universal Music Group CEO Doug Morris

Despite Apple’s support for a DRM-free internet, the big music labels and Hollywood are not likely to dispense with DRM and their legal enforcement teams anytime soon. Yet the prospects for a post-DRM audiovisual economy and culture present a challenge to the neo-liberal frameworks that have largely guided internet regulation to date. Less an electronic frontier of market competition and consumer choice, DRM regimes expose the failed attempts of oligopoly capital to maintain market leverage over artists and consumers in an online environment. It is not the ethics of market competition and consumer choice that provides alternatives, but an ethics of collective bargaining where laboring artists and consumers share collective interests that require agreed upon mechanisms for user payments, creative compensation and electronic distribution. Collective societies in the US such as ASCAP provide precedents for collectively compensating creative content makers through blanket licensing agreements. The state consumer rights agencies in Europe demonstrate that internet music consumers benefit when collectively represented by independent government authorities. When consumers and laborers have organized representation through compulsory licensing arrangements they can negotiate with market players to develop innovative mechanisms and business plans for circulating audiovisual culture unencumbered by restrictive DRM regimes. This is far from the market evangelism and rugged individualism of the internet enthusiasts of Wired magazine or the cyber utopianism which grew out of a counter cultural movement that prognosticated the withering of corporate and government bureaucracies. Compulsory licensing requires representative organizations from the corporate, government and user sectors to set rates, apportion compensation and enforce compliance. Messy and bureaucratic? Perhaps, yes. A potential future for a more vibrant and just audiovisual internet culture? Perhaps, if we organize.

Image Credits:

1. Steve Jobs

2. Zune Squeeze

3. Universal Music Group CEO Doug Morris

Please feel free to comment.

A very insightful piece, John. The evolution of technology by both producers and users that is constantly expanding and growing the ways content can be distributed (legally and illegally) makes these arguments especially necessary and even urgent. I’m thinking in particular of the court decision today to restrict Comcast’s use of network-located DVR technology: while not necessarily the same type of content mentioned here, it still illustrates the way the digital realm has both revitalized content delivery choices for users AND made the corporate sector extremely skittish to the point of litigious action. But one question remains for me: I can easily (perhaps too easily) see the representatives assembling for the corporate and government interests in a compulsory licensing scenario; who would adequately represent the millions of diverse users invested in digital content?

I think the question of who would represent the body of users is a salient one — I worry that this would become an instance of mainstreamed tyranny, like the MPAA ratings board. I agree, though, that something has to change.

SageSupportNumber.Com is a US-based company that has

grown into an internationally recognized provider of

accounting support services with a highly regarded client

base..

http://www.dailymotion.com/sag.....portnumber

Quickbooksupdate.support is a US-based company.Quickbooks Online Customer Support Chat to get full access to our support

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u8Ws_OCvn54

I want to read your blog. There is a lot of good information on this blog, I loved reading it and I think people will get a lot of support from this blog. Sam, I have written this kind of blog, you will get a service & Support from this too. I hope you like my blog, Users will get a lot of information from this blog. I hope you get a lot of Fully support & help from this blog. visit for my site