Democracy in Fifteen Seconds

by: Chuck Tryon / Fayetteville State University

Few events call attention to advertising and its relationship to broadcast television as much as the Super Bowl, one of the few remaining media events that engage a collective, national viewing audience. Because it is one of the few live events to attract such a large national and international audience, Super Bowl broadcasts have recently become the site of energetic debate about what kinds of images are appropriate for broadcast, with Janet Jackson's infamous halftime performance inspiring the Federal Communication Commission to crack down on indecency. However, as John McMurria reminds us, the FCC's narrow definition of indecency ignores other forms of exclusion that take place on Super Bowl Sunday.

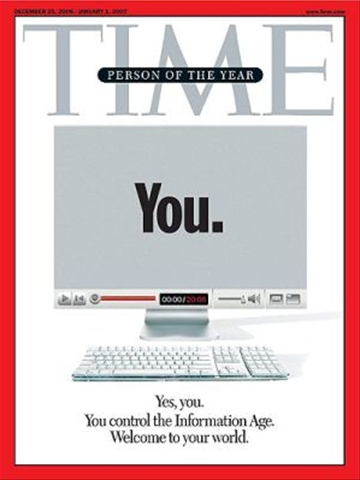

In contrast to Super Bowl Sunday's commercialization, media pundits have designated 2006 as the year that ushered in a new era of participatory culture, with Time Magazine famously naming “you” as its “Person of the Year,” citing the widespread practices of blogging, vlogging, and podcasting as examples of a nascent digital democracy in which everyone produces as well as consumes media and anyone can become a star. In particular, the video sharing site YouTube has gained a reputation as a more authentic alternative to the corporate media, one that invites participation from anyone who wishes to submit or watch a video (or several hundred). This rhetoric of authenticity informs a contest sponsored by CBS, “15 Seconds,” in which YouTubers are invited to submit fifteen-second videos to a contest hosted on the website with the winning video potentially appearing on CBS on Super Bowl Sunday. The contest, which was announced on The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson, requires that each submitted video also communicate an “inspiring message” and stipulates that contestants avoid using any copyrighted content in their videos (which eliminated a number of fairly entertaining Bush mashups). A panel of judges will evaluate the videos based on their creativity, message, quality, taste and tactfulness, and goodwill, choosing five finalists every two weeks before selecting one “favorite” for possible broadcast during the Super Bowl, an evaluation process that seems rather distinct from the more populist modes of evaluation that occur on video-sharing site. Contestants are also required to submit the videos via YouTube to CBS's “15 Seconds” group, a move that can certainly be read as a means to draw attention to CBS's content on YouTube and to identify the network with YouTube's participatory, community-oriented reputation.

To be sure, YouTube's reputation as a democratic site featuring unfettered personal expression and political commentary has been challenged after the site was sold to Google for $1.65 billion dollars, as John McMurria discussed in a recent Flow article. And while it would be easy to mock CBS's attempt to capitalize on the rhetoric of democratization associated with YouTube, glancing at the videos over the course of an afternoon, I found myself taken in by the ways in which the videos negotiated the limitations of the contest through the medium of web video. The CBS contest raises some crucial questions about how video sharing will be packaged and marketed, particularly as YouTube continues to work with broadcast and cable television. While web-enabled video sharing holds out the promise of democratization, offering everyday people the opportunity to express themselves in a public space, what happens when a major network such as CBS borrows from that language of democratization? While the contest has only captured the interest of a comparatively small number of participants–just over 100 videos have been posted in the ten days since the contest was announced on The Late Late Show–it still raises questions about the relationship between web-enabled video sharing and network television.

Unlike most YouTube content, the CBS contest requires participants to convey the “inspiring” message with their fifteen seconds of fame, demanding concise, sound-bite style statements, a limitation that several of the contestants refer to obliquely or directly in their entries. While these constraints typically have engendered vague calls for tolerance or world peace, even with those limitations, contestants managed to make use of many of the techniques characteristic of web video as a medium. In a number of the videos, participants directly address the camera, openly appealing to the sympathies of the viewers. This sense of authenticity is underscored by the setting and production values of the videos. Instead of carefully produced commercials with clearly calculated messages, these performers carefully present themselves as everyday people, filming in their cluttered bedrooms or their kitchen table, often with cheap digital cameras. Others tap more explicitly into what Henry Jenkins has called YouTube's “vaudeville aesthetic,” , filming a cat vlogger admonishing viewers against racism, performing short rap videos, or conveying messages through whimsical hand-drawn animation. The most memorable quality of the videos is this homemade status, the degree to which these videos unapologetically acknowledged their low-budget production values.

Watching all of the CBS videos consecutively over the course of an hour or so, I found myself increasingly caught up in the conversations that seemed to be taking place. While the videos themselves were produced independently, many of them repeated similar desires for peace and tolerance, with several specifically addressing the ongoing crises in Iraq and Darfur, while others sought to cut through the clutter of Super Bowl Sunday by offering us fifteen seconds of quiet. At the same time, I also couldn't help but notice that most of the contestants were white, middle-class males, details that should call attention to issues of access to participation in the culture of Web 2.0. While only a fraction of the Super Bowl audience will see most of these videos, they do raise important questions about the value of participatory culture as well as offering a careful consideration of what can and cannot be shown on network television.

Image Credits:

1. Super Bowl XXXIX

2. Time Magazine

3. YouTube Globe

Please feel free to comment.

limited participation

I am glad that Tryon acknowledges that while YoutTube and other sites attempt to include the majority of people in creating and distributing their own media – many others are excluded due to reasons of economics. It is important to remember that while these sites are open to the public to share videos and such, the limitations concerning access still affect many, which should create some hesitation in labeling the individual as the person of the year, if not all are able to participate. In effect the “you” of the Time magazine article does not include everyone.

Pingback: FlowTV » “Why 2008 Won’t Be Like 1984:” Viral Videos and Presidential Politcs

Pingback: FlowTV » Bringing the War Back Home: YouTube and Anti-War Street Theater

Pingback: The Chutry Experiment » Debating the YouTube Debate