How TV Met Narrative Sophistication

by: Craig Jacobsen / Mesa Community College

Fox aired nine episodes of Reunion in the fall of 2005. While that hardly makes it last year’s great success story, it was an interesting failure. Like the similarly cancelled Surface on NBC, Threshold on CBS, and ABC’s Invasion, Reunion hoped to borrow some mojo from the previous season’s hit, ABC’s Lost. But while Surface, Threshold and Invasion tried to cash in on the weird factor of Lost, Reunion borrowed from the hit show’s narrative structure, namely its love of flashback.

The show began with a present-day funeral before jumping back twenty years, following a group of high school friends through the years, one year per episode, revealing along the way whose funeral we saw in the first episode, and how that character had died. If we believe Fox’s advance promotion, Reunion marked “a groundbreaking concept in series television as it chronicles the lives of a group of six friends over the course of 20 years – all in just one season.” Or it would have if it had run for a whole season. Like the three shows about water-loving aliens, Reunion was not destined for longevity.

Despite the failure of Reunion, this fall brings us The Nine on ABC, a similarly-structured show. Viewers will follow nine strangers brought together as hostages in a bank robbery. As we watch their lives after their rescue, we’ll get flashbacks that reveal what happened during the siege. So why do the networks suddenly love analepsis? Since when did flashback become more than a few moments of backstory here and there?

I’d argue that this genealogy of analepsis demonstrates network broadcast television’s increasing sophistication as a narrative medium. Given network television’s conservative approach to narrative structure (just look at how many sitcoms still employ the same basic structure as I Love Lucy), any trend toward more complex narrative forms demands attention. That The Nine got a chance after the failure of Reunion a season earlier demonstrates ABC’s belief that that a show can be structurally atypical and still succeed. Reunion is just the latest show to benefit from the networks’ increasing receptivity to narrative complexity, an openness that’s been building over the last five years or so.

Let me be clear. I’m not commenting on whether American network television currently has or has had the courage to confront unpopular, political or complex subjects. I’m not concerned with whether broadcast has been as willing as cable to challenge viewers’ sensibilities. I’m interested here in complex form rather than novel content. Television has been reluctant to explore the possibilities of its potential as a narrative medium, preferring instead to stick close to the shore of linear chronological presentation and objective point of view. Though there have been experimental shows, the most visible experimentation has frequently been limited, often only a one-off aberration, as when M*A*S*H filmed an episode using a subjective point of view, through the eyes of a patient, rather than employing its default objective perspective, or the episode of Seinfeld presented in reverse chronological order.

Over the last several years, shows willing to explore the narrative potential of less-common narrative strategies for more than an episode have become more common. This trend’s most obvious recent historical marker is the first season of 24 in 2001. While the show sticks

with a predominantly straightforward linear chronology, it operates under the conceit of “real-time” narrative, a structural decision that denies the show much of the “grammar” of visual narrative developed in film and television, and forces a kind of plotting that compresses events. The show’s success demonstrated that a network viewing audience could adapt to and appreciate a narrative presentation that challenged at least some of its expectations.

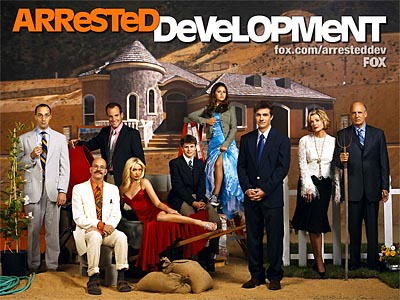

Another rather obvious milestone is another Fox show, 2003’s Arrested Development, whose extensive use of an omniscient voiceover narrator offered an atypical way to assemble scenes and offer insight into characters. Though the show struggled to survive through three seasons, it had time to explore and exploit the potential of the structural decisions made at the show’s creation. And that’s really what’s interesting here, that there are increasing numbers of programs willing to adopt unusual fundamental narrative premises that then both impose constraints upon how they can tell their stories, and simultaneously allow for an examination of the potential of those premises.

I’ll touch only briefly on 2004’s debut of Lost, though its obsession with flashback and hit status are critical to the increasing acceptance of narrative experimentation. The centrality of analepsis to the show is in itself unusual, but what’s really curious is the show’s atypical employment of the device. Whereas flashback is most often used to explain characters’ motivations or reveal previous events, the flashbacks in Lost create as many questions as they answer.

The success of 24 and Lost helps explain why shows like Reunion or The Nine can not only employ but also promote their unusual structures. Thus Fox’s use of “groundbreaking concept” to describe Reunion. Clearly the networks believe that some viewers find such experimentation intriguing. But it isn’t enough to find some suggestions of a television avant garde. For narrative exploration to be more than an aberration, we’d have to be able to find it in shows that aren’t being promoted as “edgy.”

NBC’s The Office, while quirky, isn’t marketed as cutting edge. Though the show borrowed its pseudo-documentary format from the British original, the American series has already aired more than twice as many episodes as the original, giving it more time to play with the implications of having a camera visible to the characters. Its interview segments allow characters to speak directly to viewers while, thanks to the documentary premise, not entirely violating the fourth wall. But it is when the camera follows the characters that the most interesting narrative moments occur. When characters grown accustomed to the camera’s presence suddenly notice it again and alter their dialog or actions accordingly, or when the camera surreptitiously films the characters’ private moments, we’re seeing the exploration of narrative form: how do you convincingly capture intimacy when you’ve taken away the camera’s privileged invisibility?

If “quirky” is a step below “edgy,” where we really want to see evidence of this trend is amongst the banal. CBS’s How I Met Your Mother, a situation comedy with obvious debts to Friends, Seinfeld and Arrested Development, debuted, like Reunion and The Office, in 2005. The show’s subject matter, the romantic lives of twentysomething New Yorkers denies it “edgy” or even “quirky” status, but its atypical narrative structure and its survival into multiple seasons demonstrate that narrative experimentation is going mainstream and surviving there.

How I Met Your Mother employs a voiceover narrator who provides commentary. What makes this more than a simple borrowing from Arrested Development is that the narrator lacks omniscience, and is instead a future version of the show’s central character. Set primary in contemporary New York, the show follows Ted as he looks for his soulmate. The framing narration has future Ted telling his teenage children how he met their mother way back in the Oughts. Because future Ted knows how things work out, he sometimes reveals information in passing. For example when he tells his children about their “Aunt Robin” he excludes the obvious love interest character from being the eventual titular Mother, thus intensifying the show’s central, if less than gripping, mystery: who will be Ted’s soul mate?

That How I Met Your Mother is hardly groundbreaking television is precisely the point. That atypical narrative strategies now appear, without fanfare (CBS barely mentions, and certainly doesn’t actively market, the show’s narrative structure), in successful if unremarkable mainstream broadcast shows demonstrates that television may be ready to fulfill its potential as a sophisticated narrative medium.

Image Credits:

1. Reunion

2. The Nine

3. 24

4. Arrested Development

5. The Office

6. How I Met Your Mother

Please feel free to comment.

I love that you chose to “illustrate” your article with cast photos. I especially appreciate the obvious difference between the dramatic shows (dramatic cast photos) and the comedy shows (silly-ish cast photos). And then there’s The Office, which is somewhat in the middle–showing a semi-serious cast photo in line with a serious show, as if the mockumentary were a documentary and these are people who take themselves and their work seriously. Yet, knowing the show, you can read the comedic elements in based on the characters, who, as characters, are not often meant to be taken seriously at all. I would argue that of the cast photos, this is the most narratively driven, and the one that requires the most viewer knowledge to “read,” part of the show’s overall built-in joke. Another aspect of networks and audiences embracing narrative complexity, perhaps?

form vs. function

I like how this article is a weaving that demonstrates how, ultimately, you can not seperate form and function. In other words, in the act of talking about the form, or the structure, of the television narrative seperate from it’s “content,” you reemphasize how critically connected they are. What I’m beginning to wonder is how might genre affect this? Or, how might genre fit into this particular argument? I think that speculative genres (fantasy, horror, & SF) generally allow for the exploration of form because there is an expectation of the “weird” in the narrative content.

form vs. function

I suspect that genre plays in by making one or another narrative strategy more likely. For example, mystery (_Reunion_, for example) seems to lend itself to flahback, because of the potential for analepsis to reveal causes or motivations. Voiceover narrative allows for a distanced commentary that probably works better ironically (as part of comedy) than straight (as drama). As for the “weird” genres, I think that while the audience might be more receptive (for the reasons you mention), there may be a tipping point. I think of the film _Memento_, where, unravelled, the story is pretty simple (few characters, clear motivations, limited actions). In that film the structure is enough to process. A more complex narrative, perhaps one from science fiction that requires viewers to be decoding the fictional world’s premises, might create an overly complex narrative. If narrative complexity is a trend that continues, I think we’ll see that one of the tricks to success is finding the balance point between complex form and complex content.

Narrative Forefathers

What a great discussion of narrative form! While I certainly appreciate Lost’s contribution to network television and agree the medium is in an age of “increased sophistication,” I also wonder if this transition was conditioned by a variety of factors: mimicking its competition and the innovations occuring in the “ghettos” of cable television networks (I can’t help but think about HBO’s Dream On); perhaps exploiting the very same creative resources in an age of consolidation where cable networks and broadcast television share the same corporate address; trying to mark the “difference” of certain programs in an era that has seen a proliferation of reality television and prime-time game shows; and, mirroring Jean’s comments, narrowcasting to an audience defined by an aura of “cool” and a state of “in-the-know” to increase its loyalty and identification with a series and its characters – perhaps a newer, younger, hipper definition of “quality.” Nothing too concrete here, just some additional fodder to consider! Great column!

Further Reading on TV Narrative

If readers are interested in the issues raised here about TV narrative, I’d point people’s attention to the new issue of The Velvet Light Trap, where both Michael Newman and I have articles discussing these topics in depth (and at least in Michael’s case, written in an accessable & engaging tone!). If you’re at an institution with access to Project Muse, full text online is available at http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/t.....t58.1.html – hope the conversation continues…

Expanding TV Narrative

Interesting thoughts on these shows. I especially like how you’ve categorized them on a spectrum radiating out from the “norm.” This is a calculus I’m certain goes on relentlessly in the development of these series, i.e., how much “edgy” form can we get away with? Another show from this season, Heroes, has upped the ante with its copious use of dreams and flash-forwards (most notably thus far the closing scene to this week’s episode). What’s interesting is how NBC (not the show itself) clearly explains what’s going on at the open of every new episode, which suggests to me a kind of “assisted” narrative complexity that’s very different from how Lost (for example) functions. In other words, they’re helping the audience like the show.

I just wrote about the prospects for this year’s crop of serial narratives (including these more complex shows) over on my blog (http://dkompare.wordpress.com).

Pingback: FlowTV » The Simultaneous Dawning and Twilight of Broadcast Network Narrative

Pingback: FlowTV » Film is the New Low, Television the New High: Some Ideas About Time and Narrative Conservatisms

Pingback: Measuring and visualizing the increase in narrative complexity in TV series – State of the Art « DH101

Pingback: Updated State Of The Art | Analyzing TV series and their narrative complexity