The Dynamics of Political Re-Branding

Among political communication analysts in Britain, a lot of recent interest has been generated in “political re-branding.” This phrase indicates a project that, using some of the methods developed in commercial marketing, attempts to reposition a political party within political space (to a large degree a matter of cultural space and media space).

The idea of “branding” carries further the notion that political party and leader identities have become even closer to brand identities, built by a combination of close attention to existing market profiles and customer preferences (to some, this latter factor gives a democratic dimension which older forms of political “hard sell” lacked) together with abilities in promotional strategy. One has to be careful about collapsing the real differences between commercial and political practice but nevertheless the comparison is useful. In a number of countries, a variety of factors have combined to make it so, albeit with strong national differences. Among these factors we can note a weakening of traditional party loyalties, a reduction of key ideological differences (notably, a convergence on basic economic policy), intensified conditions of media visibility and an electorate increasingly used to behaving as a “consumer” as well as (if not rather than) a “citizen.”

Commercial brand theory sees “brand personality” as a key integrating factor in building brand value. In politics, such “brand personality” is inevitably personified by political party leaders, a group with a long history of iconic public projection.

Why “re-branding” is so interesting and significant is because it replaces the relatively stable, or at least slow-moving, character of traditional political identity which a much more aggressively and strategically mobile version, alert to the conditions of the “political market” and the changing profile of media relations. This version appears to give added emphasis to “managerialist” concerns, the ability not simply to inspire but “to deliver.”

In Britain, David Cameron, elected as leader of the Conservative Party last year, is the obvious focus. Since taking office, he has gone about the re-branding of his Party in a way that is unprecedented in its scale and styling. In fact, it raises questions about whether re-branding is really the right word for what might appear to be a major shift in the essential nature of the product itself. Reference by commentators is frequently made back to the emergence of “New Labour” as a restyling of the Labour Party in the early 1990s, although this was accomplished across a period of years and several leaders, however decisive Tony Blair was to its success. Interestingly, this was also a change that, cosmetic or semiotic as it might appear at one level, was actually about key values and policy commitments.

One of Cameron's first moves was to adopt a softer version of Labour's re-labelling tactic. Although a change to the actual name of the Party was considered and rejected, Cameron began to use “compassionate” in front of “Conservative” and “Conservativism” on all possible occasions, a direct semantic counter to the idea of “hardheartedness” that had become strongly attached to the Party, even by those who applauded it for being so. Then followed his first policy emphasis, which was to project deep environmental concern. Again, this had a novel semiotic dimension in the “Vote Blue, Go Green” slogan for the Spring 2006 local elections (Blue is the traditional colour of the party). Other, equally bold, shifts in political space were undertaken, with speeches emphasising the need for happiness to be seen as a greater value than money, for gender equality and for a greater recognition of the value of the public services. Rather than opening up clear space to the conventional “Right” of the Labour Party, which is what his predecessors had usually been forced to attempt, Cameron's tactics seem to have been to go radically “central” by actually placing some of his policy lines to the “Left” of Labour!

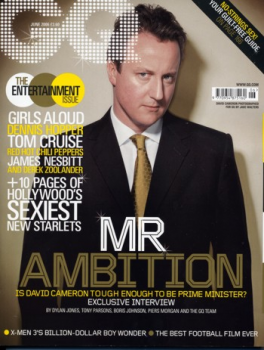

Cameron's media visibility has been marked by a calculated emphasis on the informal, taking this further than level of “casual politics” (home with the family, taking the children to school, relaxing at weekends) already established as a brand requirement for most leading politicians. The most defining image to appear in the press in the first few months were photographs of him cycling to Parliament, with full cycling gear and helmet. BBC television helped establish this, choosing to cover his journey to the House of Commons to hear the result of the leadership election in 2005 by tracing his cycle journey from a helicopter! Even the recent news that a chauffer-driven car follows him carrying his suit and his papers has not entirely subverted the strength of this projection. A few months ago, it was reinforced by press agency shots of him driving a dog sled on a Norwegian glacier as part of a fact-finding trip about global warming. This June, in a rather different framing, pitched more at smart, cooler aspects of professional culture, he appeared on the cover of the men's magazine GQ with the headline “Mr Ambition.”

It seems clear that Cameron's key tasks as a re-brander are not only those of getting the public to accept the new brand values he is promoting but of getting existing party members to “switch” from the old values which many of them continue to find attractive. If he achieve some success here, then this “turn” in mediated politics will almost certainly require the Labour party to undertake some “re-re-branding,” meeting Cameron's challenge and distancing itself from what is now seen as the negative part of Labour's ten year period of office under the once unbeatable brand-leadership of Tony Blair. British politics is about to enter a new and volatile phase of promotionalism, one in which television will, as ever, be key strategic ground.1

1I discuss the broader issues of political culture and media power implicated here in my chapter “Media, Power and Political Culture” in Eoin Devereux (ed.) Media Debates, forthcoming from Sage.

Image Credits:

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Popkonservatismen: Det är okej att vara tory - DN.se