CSI is Effecting Me

IN ADDITION TO OUR REGULAR COLUMNISTS AND GUEST COLUMNS, FLOW IS ALSO COMMITTED TO PUBLISHING TIMELY FEATURE COLUMNS, SUCH AS THE ONE BELOW. THE EDITORS OF FLOW REGULARLY ACCEPT SUBMISSIONS FOR THIS SECTION. PLEASE VISIT OUR “CALLS” PAGE FOR CONTACT INFORMATION.

Recently, the “CSI effect” has been a popular topic in both print and broadcast media. The phrase has gained international attention, even making it into the English language newspaper here in Hong Kong where all three versions of the CSI franchise are screened on either free to air or pay television. The CSI effect is a term coined by some in the legal community and the media to describe jurors who are influenced by CSI: Crime Scene Investigation to the point where they develop unrealistic expectations about the evidence used in trials. According to this theory, the quality of real evidence, usually more flawed than its television incarnation, fails to meet their standard. As a result, they are allegedly freeing more defendants. While this is the common understanding of the phrase (and an interesting debate for audience studies researchers), the CSI effect has taken on broader notions in public discourse.

For television critic James Poniewozik, the effect of CSI has been to make network drama more homogenous. The show's success has not only created its own spin-offs in the form of CSI:Miami and CSI:New York, but its “crime-science-confession formula” is being repeated in various procedurals that now populate network television. Writing in Time, Poniewozik suggests that while the special effects of the CSI franchise (cameras that “zoom through blood vessels”) produce television that looks “21st century,” the actual outcome is conventional television that does little more than revisit the successful formula found in dramas like Dragnet.

While CSI owes its narrative structure to earlier police procedurals, the special effects of the show, its “21st century” look, also reflect a more recent preoccupation with the body. In her work on the spectacle of bodily trauma in media and social space, Anita Biressi suggests that “the climate of the 1990s onwards has been one in which body management, in all its manifestations, has become a central preoccupation” (“Above the Below”). Jason Jacobs argues that the decade saw “an unprecedented intensification of the medicalization of everyday life” which was characterized by “regular health scares, the theorization of the 'risk society,' [and] the promotion of 'healthy living'…as a moral as much as a medical imperative” (Body Trauma 2001, 12). Television added to the discourse with an increase in hospital dramas where caring and quirky medical professionals attended to the physical and psychological needs of the distressed. For Jacobs, the growth of these dramas is a direct result of the medical seeping into everyday life. While popular science may have scared us in the 1990's, it also gave us answers–to slimming down, preventing disease and keeping safe.

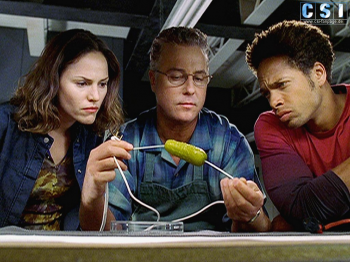

The recent shift from hospital dramas to the fictions of medical investigations reflects a continuing desire for medical science to calm our fears and restore our faith. One of the most successful ways that CSI achieves this is by making science visually accessible. Slick special effects reveal the body's internal response to bullets and blades. Graphics and flashback scenes literally walk us through the crime. Rather than just listening to the complex language of forensics, the CSI audience is witness to powerful images that allow the body to give up its secrets. Dead bodies are not simply recovered from crime scenes; they are crime scenes. Science solves the mystery in part, because seeing is believing.

For some critics, CSI's faith in science as crime solver is a dangerous form of fundamentalism. Writing in the January 2005 issue of U.S. Catholic, ethics professor Patrick McCormick argues that CSI promotes a “forensic fundamentalism” where interpretation and analysis is largely absent and evidence is never incomplete or ambiguous. McCormick sees this as a dangerous disconnect in a world where death sentences are commuted on the basis of faulty evidence and millions of crimes go unreported and unsolved. He suggests that part of the show's appeal lies in our desire for a straightforward moral universe “where the difference between guilt and innocence and right and wrong is a matter of black and white, a question of a negative or positive lab result.”

For me, McCormick's argument is the true essence of the CSI effect and its greatest strength. CSI's unwavering faith in science goes some way toward quieting the climate of fear that media often promotes. In its fictional victories over brutal crimes, we are reassured. Science tracks down the criminal, every time. It does not fail us. It gives us answers. And we want answers. And television wants us to want answers. When Aaron Sorkin wrote “Isaac and Ishmael,” The West Wing's response to 9/11, he had a character ask “why do they hate us?” in reference to terrorists. Sorkin didn't really answer the question but CSI does in the form of everyday crime. On the show, science is often the answer to both the 'how' and 'why' of murder. Each week suspects are faced with the incontrovertible proof of their misdeeds, which typically leads them to reveal their motivations. The crime is solved on all levels and we feel secure in the knowledge that bad things happen for a reason. If CSI effects us, it is because we want to believe that DNA evidence, amazing databases and teams of people in lab coats are able to expose dark secrets. It is satisfying to know that evil has a logical root cause. The opposite is what allows our national leaders to use labels like 'evil-doers' without the need for introspection. The opposite is too easy.

Works Cited

Biressi, Anita. “Above the Below: Body Trauma as Spectacle in Social/Media Space.” Journal for Cultural Research. 8.3 (2004). EBSCO. Lingnan University Digital Library, Hong Kong. Accessed 13 Sept. 2005.

Jacobs, Jason. Body Trauma TV: The New Hospital Dramas. London: BFI, 2003.

McCormick, Patrick. “Science Fiction.” U.S. Catholic. 70.1 (2005). EBSCO. Lingnan University Digital Library, Hong Kong. Accessed 26 Apr. 2006.

Poniewozik, James. “Crimetime Lineup.” Time 8 Nov. 2004. EBSCO. Lingnan University Digital Library, Hong Kong. Accessed 26 Apr. 2006.

Image Credits:

Please feel free to comment.

But I watch it for the human drama…

This column is interesting to me because, even though I know that many many people are watching CSI for the crime scenes (and enrollment in such training has sky-rocketed thanks to these types of shows), I don’t watch CSI for the crimes.

Okay, so first I have to admit, much to the chagrin of many of my grad student friends, that I watch CSI. And I actually hate to miss a week. But it’s not because I care at all about the next gross-out case. It’t because I genuinely want to know what is going on each week with the members of the CSI unit. The psychology of the serial cast is far (far) more interesting to me than the episodic narratives.

I wonder to what extent people who watch and get “turned on” to crime scene forenics also follow the long-term character arcs? I doubt it’s an “all or nothing” proposition, but because it leans so far in one direction for me, I’m curious about the other side.

Watching CSI religiously

I agree with Melissa Crawley’s observations on CSI: its most important modification to the standard crime-detection-confession genre formula is not its reliance on glossy special effects, but the role science plays in the drama. I have to wonder what this says about America’s faith in science as a belief system, as a way of figuring out who is bad and why they are bad. We seem to still be a deeply religious society, yet we’re increasingly willing to accept scientific explanations for anomalous human behavior. And so while many Americans may say that they believe Jesus Christ is the son of God and attend church every Sunday, their everyday actions as members of juries, as viewers of CSI and as consumers of technology betrays an increasingly slavish devotion to science. Not to say that Crisitianity and belief in the scientific method are mutually exclusive. I’m not sure how psychology-heavy CSI is, but it strikes me that the greatest threat to Christianity and other religions that concern themselves with the deeds of humans is not forensics but neuroscience and psychology. Proving definitively that a man killed a woman is one thing, but proving that he did so because of a chemical imbalance or a failure to attend his weekly psychiactric meetings has drastic consequences for the way people view morality and free will.

Curiously, Americans’ motivation for voting for certain initiatives remains as tied to religious dogma as it ever was. I think Americans have a exaggerated sense of power as voters, and don’t regard their choices as consumers, employees, or jurors as important or worthy of moral scrutiny. Perhaps those who watch CSI are far less religious than those who don’t and we’re talking about the proverbial 2 Americas (red vs blue) again, but I’d wager there’s some overlap there.

At the same time, Jean is right to highlight the oft-overlooked appeal of the human drama on CSI. I must confess that I haven’t seen much of this show (the characters seemed a little too square to be likable), but this article, along with CSI’s enduring popularity, makes me think I should give it another chance.

Pingback: FlowTV | Special Features on Flow Needs You!

the body

Just to add that I think that the medicalisation of societies is a profoundly conservative development which seems also rather paradoxical. On the one hand science is widely perceived as part of what we might call ‘the human problem’ – i.e. humans destroying the planet and each other. But on the other we have popular tv shows where science is foregrounded and stylised in exciting and dramatic ways. In that sense CSI has it both ways: we get the excitement of seeing the application of science but in the service of revealing the profoundly dark nature of humanity. Again, I would see this as reactionary, in terms of ideology. However, this is not a comment on the quality or achievment of these shows.