The Lure of American Idol Explained: Parasocial Relationships and Emotional Vicarious Living in Live TV

IN ADDITION TO OUR REGULAR COLUMNISTS AND GUEST COLUMNS, FLOW IS ALSO COMMITTED TO PUBLISHING TIMELY FEATURE COLUMNS, SUCH AS THE ONE BELOW. THE EDITORS OF FLOW REGULARLY ACCEPT SUBMISSIONS FOR THIS SECTION. PLEASE VISIT OUR “CALLS” PAGE FOR CONTACT INFORMATION.

I admit it. I’m a reality TV junkie. I’m not proud of it, but it’s true. I always try to make people believe the reason I watch is because “I’m doing research.” While sometimes that is true, I just plain like it. However, a contradiction exists within me. I know watching television is not necessarily good for someone’s brain. My husband constantly asks me how an intelligent, educated person like myself could get sucked in by some of these “mindless” reality TV shows. I have to admit, he has a point. Even I wonder sometimes. But I just come back to the old standard line: “Hey, I’m doing research.”

One of my all time favorite reality TV shows is the ever-popular American Idol. It is consistently one of the nation’s number one television series in practically every demographic. Why is that? What makes it so popular? I think the answer lies in two areas: parasocial relationships and emotional vicarious living. First, let me talk about the parasocial relationships.

Each week, the audience develops what is termed “parasocial relationships” with the contestants. The term “parasocial interaction” refers to the fact that people build relationships with media characters that are like the ones in their lives (Harris 25). Sometimes people become so emotionally connected to the “characters” (fictional or real) that they feel like friends or neighbors. As a result, they tune in to their program to “check in” with their “friends” and see what is going on in their lives.

It has been confirmed by research that many people develop parasocial relationships with television personalities — either fictional or real (Rubin & McHugh 291). In fact, Perse & Rubin (1989) found that these kind of relationships have many of the characteristics of real interpersonal ones (76). Sometimes these relationships are so strong that the people have fantasy meetings with them and have imaginary discussions (Rubin & McHugh 282). The audience member responds to the characters based on likeability, perceived similarity, and desire to be like the character (Perse & Rubin 63).

There are so many characters on American Idol with which the viewing audience can form relationships. First, there are the judges, who have all been with the show since its inception. The dynamics between the three are fun to watch and provide a little mini-soap opera for the audience. You have Simon Cowell, the mean, nasty “tell-it-like-it-is-and-insult-people” judge. Then you have Paul Abdul — a former pop star herself — who plays the “nice girl” and frequently gets in arguments with Simon over the fact that he is being too mean. Finally, there is Randy Jackson, the judge who is nicer than Simon but tougher than Paula. The interaction and disagreement that goes on with the three of them is entertaining in and of itself. You love to hate Simon. You want to give a big “high five” and say “Hey, Dawg!” to Randy (that’s his famous “tag line”), and you feel like sitting down and having an nice little chat with Paula. Because we’ve seen them for four seasons now, they are almost like members of our family. Some we like, some we hate.

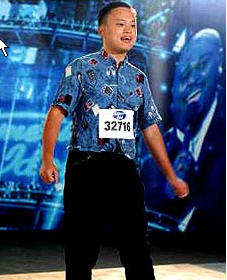

Viewers also form relationships with the contestants themselves. The reasons an audience member might prefer one over the other may not necessarily have anything to do with their singing ability. For example, many of the underdogs in the competition have had quite a following. This year it was Kevin Covias (aka “Chicken Little”), and in one past season there was the most famous American Idol reject: William Hung. While he never made it to Hollywood, he sang a very unique version of She-Bangs, She-Bangs. In the auditions, he was laughed off the stage. But then when the episode aired, America fell in love with him — mostly because of his attitude. He truly believed he could have a singing career — and let me tell you, he was pretty bad. And the funniest part of it all is that he got a $20,000 recording contract just because so many people had a parasocial relationship with him. Not too bad for an AI reject. But it’s not only the underdogs and rejects with which people form parasocial relationships. The viewing audience also has powerful emotions for their favorite singer. Getting to know all of them week after week contributes to viewers’ voting habits.

So how does this affect the aspect of live television? The suspense of wondering how your favorite singer will do and what kind of banter the judges will create is a big lure of the show. After a while, you almost feel as if these contestants are your friends and you worry about them doing a great job on live TV much the same way you would worry about your brother or sister. You have a connection, so you bite your nails, hold your breath, and even let out a gasp of fear when they mess up. Not knowing how they’re going to do on live TV is one of the aspects of American Idol that makes it utterly irresistible.

Tying in closely with the parasocial relationships, the other reason this reality show is so popular is because it serves as an emotional vicarious experience for the viewers. Watching a singing competition on live TV allows us to imagine what it might be like to be a contestant ourselves, without actually having to do so. In other words, we experience emotions through the singers’ experience. American Idol also aids the emotional experience by empowering the viewers to discover America’s next solo superstar. Therefore, in a sense, not only are we vicariously becoming a singing sensation, we are also provided with the opportunity to play “talent scout.” We can pretend like we are the ones finding the best undiscovered talent, and we can “take credit” for it.

So there’s the lure of American Idol: parasocial relationships and emotional vicarious living. Sometimes our lives are just mundane, boring, and routine. Who hasn’t imagined at some point what it might be like to be rich and famous? Not all of us will become the next superstar, so that’s where American Idol comes in. We can pretend. Because ultimately, the show provides viewers the opportunity to vicariously live the American Dream: starting with nothing and becoming something. All four of the previous seasons’ winners were “nobodies” just like everyone in the viewing audience. Then, in a matter of months, they become pop stars, celebrities, and millionaires. Talk about the American Dream! No wonder I watch it.

Works Cited

Harris, R. J. A Cognitive Psychology of Mass Communication. Mahway: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1999.

Perse, E. M., and R. B. Rubin. “Attribution in Social and Parasocial Relationships.” Communication Research 16 (1989): 59-77.

Ruben, R. B., and M. P. McHugh. “Development of Parasocial Interaction Relationships.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 31 (1987): 279-92.

Image Credits:

1. Celebration

2. William Hung

Please feel free to comment.

I wonder how the idea of “emotional vicarious living” relates to television shows like Fear Factor or Survivor. Less glamorous tasks, but with the same ultimate result of fame and fortune. Does “emotional vicarious living” still aply?

Your article defines why it is that so many shows get the attention they do, and not just with reality television, but with television series as well. I live with someone who watches the comedic television series of Friends religiously. He would often mention to me how he would find himself almost in the exact emotional state as his favorite character on the show, because to see this person struggle endowed him with pain and remorse as well. This directly relates to what you said to be how “people become so emotionally connected to the “characters” (fictional or real) that they feel like friends or neighbors. As a result, they tune in to their program to “check in” with their “friends” and see what is going on in their lives.” Furthermore, him and I would often begin to talk about which character is our favorite and why. We both found that we chose our favorite according to how we can relate to them on a personal level, or as you termed it, a “parasocial relationship.” I am heavily involved with theatre and film and have never come across this term before, and it really does explain a lot as to why certain shows capture such a heaping amount of attention. The article has also contributed to how I will choose the roles I play in the future. It would appear to be the wisest decision to play a character that society can relate to, or has related to in the past, since they, as an audience, want to emotionally connect to the person behind the camera or on the stage.