Lessons from the Undead: How Film and TV Zombies Teach Us About War

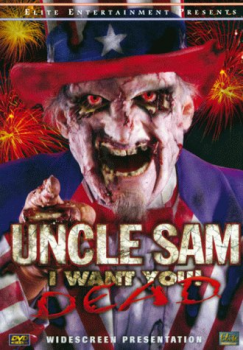

Uncle Sam (Lustig, 1996)

I am the Marine, on the border of Kuwait.

I am the soldier, only God knows my fate.

I am the sailor, on the sea, where I might die.

I am the pilot, breathing hell from the sky…

The soldiers of Iraq are waiting there to die.

Both sides are still screaming the same warrior’s cry:

Why, why, why?

— Excerpt from poem written and performed by B-movie actor William Smith in Uncle Sam (Lustig, 1996).

All genres contain room for political allegory, but some have more room than others. Romantic comedies are not necessarily incapable of making statements about ecological destruction, over-population, the dangers of nuclear weapons, or militarism, but they rarely, if ever, venture into such terrain. It’s not that melodrama and other “female” genres are apolitical; rather, they tend to reveal the political dimensions of the private realm rather than the broader political actions and struggles of the public realm. Further, genres such as melodrama and romantic comedy strive to create characters who demand intense, personal identification; allegorical films, by contrast, more often create broader character types representing big issues. Men in musicals are not always exactly what they seem — they may sometimes, for example, be rather gay — but they are generally not explicitly used as didactic symbols. It is in horror and science fiction that men function as symbols of the military-industrial complex. Or cities represent typographies of postmodern consciousness. Or monsters represent the Id, Communism, or post-Fordist capitalism.

Unfortunately, most contemporary American science fiction and horror films focus more on sexed-up action than interesting ideas. So it was big news when Showtime premiered its “Masters of Horror” series, which seemed to be an homage to old-style horror. There were no flashy stars or fancy locations, just high-concept stories. This series would, in theory, take the genre back to its 1970s glory days, when horror could be scary on a low-budget without car chases or epileptic seizure-inducing editing. Showtime marketed the thirteen-part series for its scariness and invited a number of the great horror auteurs of the 1970s to participate. But the strength of ’70s horror did not lie simply in its goose-bump-inducing power. The best horror films of the 1970s were stunning not only because they were terrifying but also because they were full of ideas: about the family (The Hills Have Eyes), Catholicism (The Exorcist), Vietnam (Deathdream), consumerism (Dawn of the Dead), and even perception itself (Suspiria). Furthermore, many of the most interesting horror films, before and after the 70s, contained strong allegorical elements, using monsters as metaphors to convey big ideas about sexual difference, capitalism, or, generally, the cruelty of human nature.

Zombies are particularly apt monsters for allegorical manipulation. Depending on writer and director, they are imbued with varying levels of consciousness and desire, and unlike Dracula and Frankenstein, they don’t require heavy back stories, they can’t be sexy or develop a boring love interest, and they have no hope of achieving any kind of happiness. These undead, decaying bodies are potent ciphers by virtue of their uncanniness. They are monsters, yet so much like us. They wander about wearing clothes we might have in our own closets: business suits, wedding dresses, nurse’s uniforms, pajamas, or combat fatigues. Film and TV zombies have been particularly well used as anti-war figures, beginning during World War I and continuing right up to the current war in Iraq.

If we define “zombie” broadly to include any non-vampiric walking corpse, the first use of zombies as anti-war symbols was in Abel Gance’s J’accuse in 1919. The film ends with the dead of the Great War returning to ask why they have been sacrificed. In 1938 Gance made the film again, this time with an even stronger indictment of the politicians and industrialists who lead citizens blindly to the slaughter. The first film had used soldiers on leave, many of whom were killed afterwards in battle. The second film used veterans of the war, many missing arms, legs, and faces. No need for special effects here. The dead march straight toward the viewer, demanding to know how the world could possibly go to war again. Had they died for nothing? By 1939 the answer was clear: yes.

Unfortunately, zombies would appear in American films of the 1930s and 1940s primarily as symbols of racist and xenophobic social anxieties. These black monsters conjured by voodoo lacked agency and humanity; they functioned as symbols of “natural” white power and black inferiority. It would take George A. Romero to reinvent the zombie as a more progressive symbolic figure. In Night of the Living Dead (1968) the putative bad guys are hungry zombies, but the real villains are the living: clueless government officials, abusive middle-class patriarchs, and hicks picking off zombies like they were at a turkey shoot. The film contains imagery obviously referencing African American oppression — mobs of whites hunting zombies with dogs and guns, a funeral pyre evocative of the final stage of a lynching, a montage of news photos showing whites roughly handling a dead black body with grappling hooks. In addition, as Sumiko Higashi has argued, through its representation of television news the film subtly references Vietnam TV coverage; the news in Night includes estimates of body counts, discussion of “search and destroy operations,” and shots of Pentagon strategists feigning being in control.

Night‘s discourse on Vietnam was subtle, but Bob Clark’s Deathdream (1974, a.k.a. Dead of Night) explicitly critiqued the war, as well as taking a few jabs at the “typical” American family. In this film, a soldier dies in Vietnam, but he comes home anyway. Like so many vets of the era, he is distant, withdrawn, strange, and addicted to drugs — or in this case, human blood, which he mainlines to defer his own decomposition. Lynn Carlin and John Marley star as the vet’s dysfunctional parents — more or less reprising the role of unhappy couple they had played in John Cassavetes Faces six years earlier. It is soon apparent that a rotting son is the least of this unhappy family’s problems. Nixon’s silent majority might not have been loudly protesting in the streets, but in the privacy of their suburban homes they were screaming bloody murder.

Uncle Sam similarly aimed its sights at the mythology of the American family, but now in the context of the Gulf War. Written by Larry Cohen of It’s Alive fame, the film tells the story of an American soldier killed by friendly fire in Kuwait. Discovered in the desert sand three years later, he is sent home to his family. His nephew worships his Uncle Sam as a hero, but his wife and sister know that the real Sam was no hero; he was a horrible, abusive, violent man who joined the Army because he liked killing people. Importantly, he is not represented as an atypical psychopath. The film emphasizes that most men are dishonest, over-sexed, and potentially violent; Sam is just at the far end of the spectrum. The military needs patriarchal violence and bogus heroic myths to perpetuate itself. What is particularly striking about the film — a low-budget, earnest, poorly acted, extremely didactic production — is that it does not embrace what has become the standard line on war protest: hate the war but love and honor the soldiers. Rather, this film asks, what kind of man chooses to join the Army, knowing that he will win medals for killing complete strangers? It dares to contend that soldiers are not inherently innocent.

Needless to say, Sam does not stay dead. His first undead act is to shoot the American soldiers who discover his body, telling them, “don’t be afraid, it’s friendly fire.” Back home, he kills a Vietnam draft dodger played by George Bush look-alike Timothy Bottoms (who would star a few years later in Comedy Central’s short-lived That’s My Bush). Dressed in an Uncle Sam costume on July 4th, our hero buries alive one flag burner, runs a second one up a flag pole by his neck, and decapitates a third and barbecues his head. He takes revenge for a kid who became psychic after being horribly maimed by fireworks, he explodes a dishonest politician with fireworks, he shoots down a dishonest lawyer dressed up like “Honest Abe” Lincoln, and he impales a pot-smoking cop on a flag pole. Finally, a Korean vet (Isaac Hayes) with a wooden leg, who has explained that heroes are just crazy killers who survive to get medals, obliterates Uncle Sam with a revolutionary war cannon. And did I mention that P.J. Soles has a cameo as the mother

of the psychic burn victim? (Though octogenarian exploitation impresario Herschell Gordon Lewis is still alive, I like to imagine him rising from the grave to make this crazy film!) In J’accuse the innocent dead returned to ask “why?” In Uncle Sam the guilty dead return to tell us exactly why. War exists, in part, because men do not recoil in horror at the idea of killing others to get what they want. It takes a psychotically patriotic corpse to show us the error of our ways.

The first narrative film to critique the current Iraq war was George A. Romero’s Land of the Dead (2005). Throughout his zombie oeuvre, Romero has encouraged us to feel for his corpses. “They ain’t doin’ nothin’! They’re like sharks,” he explains. They kill, in other words, not because they are malicious but because it is their nature to do so. It is those who enjoy killing who are most dangerous. The innovation of Land lies in further increasing our sympathy for the zombies, and in picturing them as a disenfranchised underclass. In the film’s dystopic world, a military underclass of non-zombies works for the upper-class, killing zombies and foraging for food and booze. To mesmerize zombies while they pilfer goods, the military underclass launches fireworks, which have lost all connotations of patriotism and are now called “sky flowers.” The rich live in a luxurious skyscraper, Fiddler’s Green, far removed from the zombies and poverty in the streets.

If Dawn was a critique of consumerism, Land is a critique of capitalism (and the militarism that supports it) tout court. Dennis Hopper plays the wealthy entrepreneur who owns Fiddler’s Green; he’s an obvious Bush stand-in. Unlike Uncle Sam, the film does not overtly declare itself to be about America’s wars in the Middle East, but the allegorical message is clear. Oil and greed are the name of the game. Hopper ends up trapped in his limo as a zombie who used to be a service station attendant fills the car with gasoline. Hopper escapes, only to be attacked by a former minion (John Leguizamo) who had dared to aspire to upward mobility — impossible, since he was a “spic.” Before he can be eaten alive, though, Hopper is blown up by gasoline. Iraq is never mentioned, but the gasoline inferno says it all: the greedy bastard who, earlier in the film, said he would not “negotiate with terrorists” has been hoist on his own petard.

Dennis Hopper in Land of the Dead

Joe Dante’s Masters of Horror installment, Homecoming, offers an even more direct attack on the president and the war. Dante explains that “this is a horror story because most of the characters are Republicans.” In the one hour TV film, American soldiers killed in Iraq are reanimated because they cannot be at peace until someone who will end the war is elected president. They have no malicious intent, and they don’t want to eat people; they just want to vote. They can’t be killed, but after they vote they drop dead. At first, the panicked Republican spinmeisters salute the power of American troops: nothing can kill our heroes! A Jerry Falwell clone says these zombies are a gift from God. But once the zombies start bad-mouthing the president, they are put in orange jumpsuits and trundled off to detention camps. Now the Falwell stand-in explains that Satan sent these disloyal soldiers. A skanky Ann Coulter type calls the reanimated soldiers “a bunch of crippled, stinking, maggot-infested, brain dead, zombie dissidents.” Locking up the “formerly deceased” ends up not really fixing the problem, and since there aren’t really all that many of them, the Republicans allow them to vote (and die permanently). Many non-zombie citizens have been moved by the sight of the dead to vote against the president, but the Republicans fix the count so that the president is re-elected. At this point, Arlington cemetery explodes as the dead of World War II, Vietnam, and Korea rise to take over Washington. Dante blew it by including only veterans from the past 60 years, it seems to me, but he successfully made his points: 1) It was seeing and empathizing with the dead of the war that enabled people to vote against Bush; 2) Right-wing politicians and their machinations-“Lies and the lying liars who tell them,” as Al Franken puts it-are much scarier than zombies.

Lustig, Romero and Dante all worked with low-budgets and bargain basement actors. (Notably, Hopper and Leguizamo, huge stars for a Romero film, play important but secondary roles to keep their salaries down.) Thanks to 28 Days Later and the Resident Evil franchise, zombies have recently made a pop-culture comeback, and it was only because of this that Romero was able to get his fourth zombie movie green-lit. Political zombie movies do not guarantee big box office, and, in general, no one is going to fund a would-be blockbuster, with A-list actors and a bloated budget, that is “too political.” Speaking highly of Showtime, which offered him total artistic freedom, Dante explains, “I can’t conceive of any other venue where we would have been able to tell this story. You can’t do theatrical political movies; people don’t go to them. You can’t do them on [broadcast and non-premium cable] television, because you’ve got sponsors.” It is not in spite of such practical and budgetary constraints but rather because of them that these films were able to make potent anti-war statements.

Moreover, it was precisely because Lustig, Romero, and Dante were working within the zombie sub-genre of horror that they were able to create such terrifying political statements. Horror is the best genre for literalizing our anxieties and fears, and zombies up the ante by virtue of their very mundanity. Dracula is a fancy monster, a top-shelf creature who will look soulfully into your eyes before passionately sucking the life out of you. Zombies are rot gut, the old lady in the house coat from next door who just wants to eat your brains out. Zombies scare us because, to use Romero’s refrain, they are us. At a literal narrative level, this means that in most zombie movies anyone can become a zombie, instantly making a switch from “normal” to “abnormal” (and Romero insistently asks, which is which?). But at a more metaphorical level we are all zombies because we wander numbly through life, riding the bus to work, shopping at the mall, going through the motions of normality. And not unlike the undead of Land, we are distracted by sky flowers, pretty art films and vapid Julia Roberts movies that illustrate “the triumph of the human spirit.”

Sullivan’s Travels

Like the convicts in Sullivan’s Travels (Sturges, 1942), though, we need escapist genres. Such sky flowers make daily life tolerable. We are not stupid victims of false consciousness because Arrested Development (Fox, 2003- ) makes us laugh our asses off and Now, Voyager (Rapper, 1942) makes us bawl our eyes out. (And, further, these kinds of entertainments are not as neatly apolitical as they might initially appear.) Not all sky flowers are bad, but we also need films and TV shows about rotting, bloody corpses. The Bush administration won’t even allow photos to be taken of sealed coffins of dead veterans, much less photos of the putrescence within. Viewing the dead makes war a visceral reality. It makes our stomachs turn. In the wake of a war fought over non-existent weapons of mass destruction, it is perhaps only the dead who can function as weapons of mass instruction.

Notes:

Obviously, a film like John Greyson’s Zero Patience (1993) illustrates the capacity of the musical to be overtly political. I’m not arguing that science fiction and horror are inherently more political than other genres, simply that historically they are the genres that have most directly sought political engagement.

This is not to deny the significance of a film like I Walked with a Zombie (Tourner, 1943), a compelling examination of female disempowerment and self-sacrifice within the white patriarchal family.

Sumiko Higashi, “Night of the Living Dead: A Horror Film about the Horrors of the Vietnam War,” in Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud, eds. From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990. 175-188.

Cited in Denis Lim, “Dante’s Inferno: A Horror Movie Brings Out the Zombie Vote to Protest Bush’s War.” Village Voice, November 29, 2005.

Image Credits:

2. Dennis Hopper in Land of the Dead

Please feel free to comment.

Heather,This is a really, really smart paper. Another way to look at the importance of zombies now to show us the repressed dead bodies of Iraq 2 is to compare The censored TV coverage of this war with that of the Living Room War, Viet Nam. There are no Zippo lighter incidents, most sign sof disorder and death are repressed. The maimed and disfigured bodies of the surrivors that we saw at the end of J’Accuse are now not available to public view.Though, I agree with your readings of the allegorical nature of Zobies, I do not think that horror is not th eonly allegorical genre, perhaps once again the most salient one. I think that at other times comedy and the now basiacally deceased genre of the western have also filled the allegorical role now filled by horror and Science Fiction.

Faster Zombie-cat, Kill, Kill

Thanks for the much-needed zombie column! I agree that zombie flicks are excellent vehicles for political criticism, and that they generally say more about the “normals” than they do about their animated corpses.

Nevertheless our undead brethren have changed their stumbling, bumbling behavior over the past few years, and I’m hoping that you (or anyone else) might hazard a guess as to what social/cultural force or preoccupation might be motivating the changes, if any …

For example, the post-9/11 cinematic undead are swift (28 Days Later, Dawn of the Dead — the recent “remake” of George A. Romero’s classic), strong (Undead, Resident Evil), and have the ability – albeit a limited one – to communicate with humans and their fellow damned (Shawn of Dead, GAR’s Land), thus making them noticeably different (and arguably more threatening) than the simple, sluggish, brain-famished monsters of yesteryear. And although I haven’t seen it yet, I’m guessing you could add Joe Dante’s voting GI corpses to this list as well.

PS — For those interested in reading some rockin’ zombie fiction, check out the graphic novel series, The Walking Dead (Image Comics), by Robert Kirkman.

Great piece, Heather.

This is Stuart Andrews from Rue Morgue Radio in Toronto. Shortly before Dante’s episode of Masters of Horror aired, I conducted a short interview with him about the film.

You can download an audio archive of that show here:

http://www.ruemorguedisciples.com/radiooct05.html(It’s the third episode listed on that page.)

I still haven’t seen “Homecoming” but after reading this article, it’s going straight to the top of my “must-see” list (along with the two Gance films and the Bill Lustig flick you mentioned.)

Anyway, your piece was great; very thorough and insightful. Drop by the Rue Morgue Radio messageboards sometime and say hello.

http://rue-morgue.com/forums/f.....forumid=22

Zombfication of the American Nation

I voted early absentee yesterday at the Covington courthouse. I voted a straight snubicans of the republicans ballot, and I do hope that those ballots that are later filed will find resonance with my resolve. Read this smart little essay. When you come back from the field there’s a short horror film that examines the war in Iraq in the gloomy light of a black comedy that I’d like you to see. It’s called “Homecoming” and I have it on DVD. Read this essay it’s quite good.

Pingback: Dennis Hopper and “Land of the Dead” in Boring Pittsburgh