“You Got to Know When to Hold Em”: Notes Against the Academicization of Television

by: Walter Metz / University of Montana-Bozeman

November 28, 2005 From a sociological point of view, the most remarkable thing that happened to me, upon returning from living in Germany for a year, experiencing so-called “reverse culture shock,” was not the expected panic at grocery stores the size of football fields, but the discovery of how little I knew about poker. When I left the United States in September 2003, I knew how to play five card draw, and vaguely knew there was a version with seven cards, with the salacious moniker, “stud.”

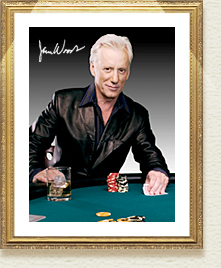

When I returned in August 2004, my television was awash with every basic cable outlet branding its own version of “Texas Hold ’em.” Because you only get dealt two cards, hold ’em is a game of statistical simplicity, making its prospects as a televisual event seems unlikely indeed. However, within a few weeks, I was completely hooked on this odd sports reality programming. My TiVo is now loaded with its permutations: ESPN’s World Series of Poker, The Travel Channel’s World Poker Tour, Bravo’s Celebrity Poker Showdown, and Game Show Network’s “Battle Royale,” whose various short series typically pit celebrities (example: the James Woods “gang”) againstpoker professionals (like Phil Laak, a.k.a. The Unabomber, so named because he hides his face behind a hooded sweatshirt after he makes an aggressive bet).

James Woods

The aesthetic conventions of television coverage of hold ’em are remarkable. The presentation of the game allows you to see every player’s “hole cards,” the two cards that are dealt face down. Players then make five-card poker hands out of these cards, combined with five cards dealt face up in a community row. Next to each player’s hole cards, the monitor indicates the statistical probability that his or her hand will win. This practice constructs the television viewer as an omniscient guru who is encouraged to treat each gambler’s misstep with utter contempt. The viewer is almost never reminded by the off-camera analysts that the gamblers’ bets and folds are made in the dark, without benefit of knowing the other players’ cards.

Armed with this televisually-constructed superiority, I went to my local Target store and bought myself the paraphernalia necessary for my own hold ’em game. Despite watching some hundreds of hours of the game on television, in real life my seven-year old son proceeded to decimate my chip stacks with alarming regularity. He then went on to beat all of his friends at daycare in their own hold ’em tournament. I will leave the discussion of the morality of children playing poker at their daycare center for another occasion. I think it is wonderful, and would defend this against the inanities of the Montessori system to my dying day, but some other time.

Arrogantly assuming that my son was just some sort of hold ’em prodigy, I proceeded to buy the various hand-held and video game versions of hold ’em. My favorite is the World Series of Poker game for the X-Box because you get to play against (and lose to) the famous poker players (Chris Ferguson, Johnny Chan, etc.) that you see on the television coverage. Alas, I will not be selling my house and moving to Vegas any time soon: in the game, you are given $10,000 for the entry fee to the “Main Event” of the World Series of Poker, and I have never made it beyond the first table, leaving the tournament in 3,000th place or below (and thus not winning any money) each and every time I have played.

Phil Laak, a.k.a. The Unabomber

I belabor this story of my television poker viewing because it indicates something crucial about spectatorship and academic life. I have learned absolutely nothing from watching television poker. I do not even remember the episodes that I have watched, such that I will watch some five or ten hands before it dawns on me that I have already seen this tournament, and know who is going to win. My wife leaves the room when I watch poker, finding it the most boring thing about me.

My wife and I have had this argument before. Before DVD sets of television shows were available, I would fill 8 hour VHS tapes with 20 episodes of The Simpsons and watch them again and again. She would berate me for watching the same thing ten times, but I would explain that sitting with the Simpsons all night was much better than crying myself to sleep. However, in the back of my mind was always the academic justification of my television viewing: somewhere down the line, I would be ready to write that great Simpsons essay, armed with an encyclopedic knowledge of the exact episode locations of all of the smart stuff. After all, this obsessive, compulsive textual analysis of The Simpsons at night was remarkably similar to my day job, where I use the same skills to teach students about the novels of Herman Melville and the films of Fritz Lang.

However, I can see no such defense for my watching the World Series of Poker. Even if there are academic articles to be written about hold ’em (a sociological understanding of the rise in popularity of the game and its televisual presence at this historical moment seems important), I certainly have no interest in writing them. And it would be incorrect to say that I am a “fan” of television poker. It is clear that there are fans (they come to the tournaments, both as players and as spectators in droves), and that television poker has a star system of professional players like any other sport, but this is not why I watch. In fact, I find most of these players, like the ill-behaved Phil Helmuth, just the sort of regressive, infantile character that I urge my students not to be like when they grow up.

Instead, I believe I am using poker in the classic sense which sees television as a piece of household furniture. The little statistical battles in television poker are soothing to look in on, and yet are fully disposable. Whether Robert Williamson III wins the hand that he is “all in” on or not, my life will continue, and in fact when I encounter this very same hand three months from now, I will not remember whether he won, and the five minutes of drama it provides will give me just as much pleasure then as it does now.

Calling television disposable is a cardinal sin in academic television studies. We fight to have our study of this medium respected by those who study William Faulkner professionally. I am not arguing that we should not wage this battle–I was just recently told that I did not get a university research stipend because my project was on Bewitched, and therefore self-evidently not serious–but I wonder if it is not time to write more honestly about the many facets of television. One such facet is absolutely academically defensible; for example, Lost is as important to the early 21st century as its equivalent, Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, was to the 15th century. However, another facet is that we watch television to relax.

Relaxation is a crucial human emotion that is pretty far afield from academic life. When we relax, we feel guilty because we are not getting the writing done that we are supposed to, even when we are at home. So instead, we are encouraged to relax more productively than “just” watching television; I feel less guilty when I am at the health club exercising because that is productive. It turns out that such productivity–keeping my body healthy–is pretty annoying and not at all relaxing.

When I was a kid, my Aunt Eleanore used to refer to watching television as “looking at” television. I always thought that was a strange way of putting it, but now I think it completely appropriate. Academic television studies have tried to shift “watching television” toward connotations of “analyzing” and “thinking.” That is good, because it focuses attention on the active, intellectual engagements we make with television. However, I sometimes also just “look at” The Simpsons and the World Series of Poker, and that is just as important to who I am as is my analytical book on Bewitched. Here’s looking at you, Phil Gordon!

Links

ESPN Poker

Travel channel World Poker Tour

Bravo’s Celebrity Poker Showdown

Game Show Network

Image Credits:

1. James Woods

2. Phil Laak, a.k.a. The Unabomber

Please feel free to comment.

I have to admit that all the glamour around poker, attracting Hollywood movie stars and building new cultural icons such as Phil Laak the “Unabomber”, on television, turning the whole deal into a spectator sport is baffling to me. I always thought gambling is something people do in Vegas or in the basements of shady bars not on mainstream television. With the proliferation of poker games on cable television, I think that the audience equally deserves shows featuring folks running up credit card debt, selling their properties or themselves, or stealing just to keep up with the cash flow necessary to stay in the game!