TV in the Season of Compassion Fatigue

The Astrodome

On the fateful Monday that Hurricane Katrina was passing through New Orleans (before the levees broke, when the biggest question seemed to be whether the Superdome’s roof would blow off) some friends and I were in a Marriott Hotel in the Florida panhandle. Like thousands of other evacuees, we were tracking Katrina’s progress via television through the city we had left behind. The storm was so large that even in Florida it was very rainy and windy and groups of people spent the whole day more or less watching the large screen tv in the hotel lounge. In mid-afternoon a cable television meteorologist reporting live from a semi-sheltered Canal Street doorway dramatically announced that he was going to make his way to a mailbox out on the street. His announcement drew mixed cries of “No!” and “Yes!” from my viewing cohort as people set aside their drinks to devote their full attention to the screen. The meteorologist-stuntman combat crawled his way out to the edge of the sidewalk and gripped the mailbox, bits of which were blowing away, and it looked as if he might join them at any moment. He made a few observations to the camera then attempted to regain the safety of the doorway — nearly there, a fierce gust suddenly blew him off his feet leading him to perform an impromptu somersault into a wall, and with that it was back to the studio. As conversation resumed and a collectively held breath released in front of the tv, a teenage boy stood up to leave but as he did so he momentarily blocked the screen, turning to face our assembled group. “That,” he informed us, “was awesome!”

I had intended to cite this anecdote of spectacle and spectatorship as a reminder of how we used to watch cable news and weather broadcasts before the terrible aftermath of Katrina, supposing that things may be a little different now. Then again, perhaps they are not as different as we would think. In a year that began with the Asian tsunami and marked its midpoint with the London bombings, mainstream television’s coverage of disaster has intensified this season with Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and the earthquake in Pakistan. As I write, Wilma, another major storm, is massing in the gulf, a wooden dam in Taunton, Massachusetts is threatening to give way after record-setting rainfall and all the networks are hyping avian flu as an imminent pandemic. I suspect I am in the majority when I turn on the news in the morning, wondering what new disaster I will learn about.

Miami County, KS Emergency Management

Television’s narratives of spectacular environmental disaster this season invite attention to climate change, car culture, overdevelopment and the perils of neglecting an underfunded and aging public infrastructure. They also provide a particular opportunity to examine our own emotional relationship to the medium and to reflect on the ways in which (non-fiction) television disaster narratives constitute epistemological evidence to a wide variety of social constituencies. Fringe groups interpreted the satellite shape of Hurricane Katrina’s vortex to resemble that of a giant fetus, a swirling reproach to a post Roe v. Wade America. Others with a residual investment in the Cold War saw significance in the names Hurricane Ivan and Hurricane Katrina while anti-semitic groups claimed that Israel’s designs on the port of New Orleans for weapons smuggling had instigated a divine retribution. Many of these interpretations build an ideological barrier between the storm’s victims and other Americans, imagining a punishment of various causes but always with the same real-world consequence delivered against the predominantly black, urban underclass of a singular American city.

Watching television this autumn has made me wonder if it might be the right time to revisit the notion of “compassion fatigue,” a term explored by Susan Moeller in her eponymous 1999 book. Moeller largely focuses upon crises and catastrophes outside the U.S. and the factors in play that work to mute American public response, particularly as wars, famine, disease, etc. are represented in terms suggesting these problems are intractable and inevitable in societies other than our own. Yet her claims retain much of their currency in a season when the rapidity with which one disaster has displaced another in the public imagination is so great and threatens to overextend our attention span and emotional limits. Moeller’s arguments might also be re-cast for a time when the “elsewhere” of foreign disaster coverage is situated domestically — Katrina put terms previously associated with foreign disaster (“refugee” and “evacuee”) into the vocabulary of American experience.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century domestic disasters are emerging as staples of U.S. media coverage and some of the factors cited by Moeller are inapplicable to these news stories. However it is clear that sustained and systemic coverage of post-spectacle catastrophe is still deemed “difficult” within the broadcast media and the chicken and egg problem of whether audiences reject such reporting or news organizations reject it on our behalf remains largely unaddressed. Many of the neighborhoods in post-hurricane New Orleans are quiet places with vast areas of destroyed and damaged residential property, closed stores, and no electricity. In a sensationalist media culture they are perhaps particularly unrepresentable. It is significant, no doubt, that the most high-profile New Orleans story in October involved the on-camera beating of a black man by police in the French Quarter — not only did this story have clear precedents tracking back to Rodney King, it was also in compliance with the representational codes of sensation and violence that drive the news media. The case affectively substituted anger for despair and also matched our affinity for blunt problems of law and order rather than the more composite concerns of resource management and reconstruction.

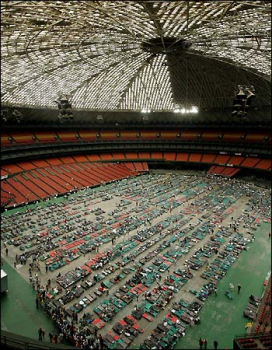

Of course, it might be pointed out that the issue is less one of compassion fatigue than of simple compassion and there would be various elements in the reporting of Katrina to support that view. One might think of the desperate attempts of rooftop-bound hurricane victims using the U.S. flag to signal for attention from passing helicopters (thus effectively claiming their own citizenship status and symbolic integration with a nation that has reinforced its connections between citizenship and patriotic iconography since 9/11). At those moments, it seemed, the victims acted from the belief that a demonstration of their ideological worth would enhance their chance of rescue. One might also recall Barbara Bush’s comments at the Astrodome suggesting that many of those being sheltered there were probably content to be housed in a sports stadium since they lived impoverished lives anyway.

The regularization of catastrophe this autumn challenges us to sustain a compassionate relation to disaster even when television maintains an exploitative relationship to it. While several cable news outlets have slightly expanded their follow-up coverage of Hurricane Katrina and a few have produced hard-hitting investigative pieces, the focus this season remains on the terrible thrill of disasters in progress.

See Also:

Tara McPherson — “Feeling Blue: Katrina, The South and The Nation”

Douglas Kellner — “Hurricane Spectacles and the Crisis of the Bush Presidency”

Image Credits:

2. Miami County, KS Emergency Management

Please feel free to comment.

response

I have to admit that when I read Negra’s article about Compassion Fatigue, I first thought she was referring to Pakistan and the recent earthquakes. After the Tsunami and the Hurricane season, the slow effort to aid the victims of Earthquakes in Pakistan has been attributed to compassion fatigue. Reading Negra’s article, however, we come to the realization that everything is propaganda. Thus, the reason that the dividing line between compassion and exploitation is hard to delineate, it is not because one is losing his mind or his spirit, rather, these concepts are becoming increasingly virtual in our world today because the Matrix is already here.

The thrill Ride of Television

In the last year disasters have turned into a wild form of entertainment. There seems to be a disaster around every corner, and you almost can’t wait to find out what it is. This article made me think about how I watch the news and I am entertained by others peoples struggles through massive natural disasters. I become obsessed with the images I see and I only want to see more, when one disaster is over I want to see another one. The news also intensifies the excitment by having people on the scene, who are facing the disaster. The article even explains how a kid thinks it’s “awesome” when a meteorologist gets blown into a wall. The news anchors help escalate the entertainment, they constantly give you updates and tell you how many people have been killed(which makes the storm look more extreme). I think it is a shame that Hurricane Katrina, along with many other natural disasters, are turned into such television spectacles. Turned into such a spectacle, that you no longer feel sorry for the victims. The victims become actors in a large disaster film